Some farmers and gardeners like to use the same ground year after year for their tomatoes. Often this works, but often it doesn’t – most commonly because of a few tomato diseases that overwinter on crop debris. The most common disease in the Northeast that leads to a tomato crop failure is early blight. In this article I will point out similarities and differences between early blight and two other tomato diseases that are commonly confused with it, late blight and septoria leaf spot.

|

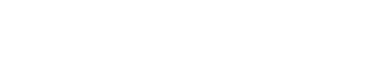

| Early blight produces concentric, target-like rings in leaf and stem lesions. The infected areas on the leaf coalesce, and the whole leaf turns yellow and then dries and falls off. Photo from “Kentucky Vegetable Diseases,” Univ. of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service, 1976. |

|

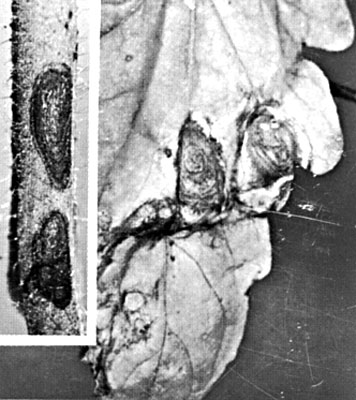

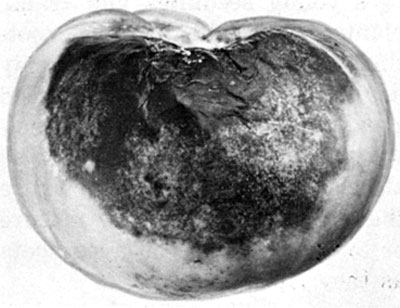

| On tomato fruits, early blight is centered around the stem end of ripe tomatoes, usually later in the season than late blight. Photo from “Tomato Diseases and Their Control,” USDA Agricultural Research Service Agriculture Handbook No. 203, 1972. |

|

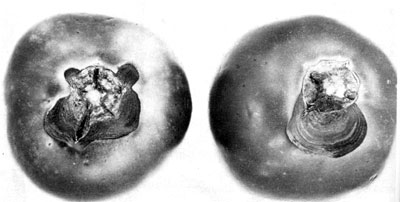

| Late blight appears on tomato leaves as pale green, water-soaked spots, often beginning at the leaf tips or edges. The circular or irregular leaf lesions often are surrounded by a pale yellowish-green border that merges with healthy tissue. Lesions enlarge rapidly and turn dark brown to purplish-black. Under humid conditions, a white mold often appears on the lower leaf surfaces at the edges of the lesions. Photo from “Tomato Diseases and Their Control,” USDA Agricultural Research Service Agriculture Handbook No. 203, 1972. |

|

| Late blight develops on green tomato fruit, resulting in large, firm, brown, leathery lesions, often concentrated on the sides or upper fruit surfaces first, but later turning the whole fruit into a brown golf ball. Photo from “Tomato Diseases and Their Control,” USDA Agricultural Research Service Agriculture Handbook No. 203, 1972. |

|

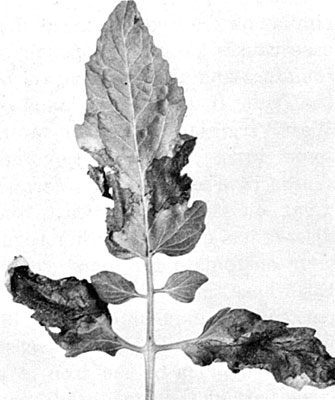

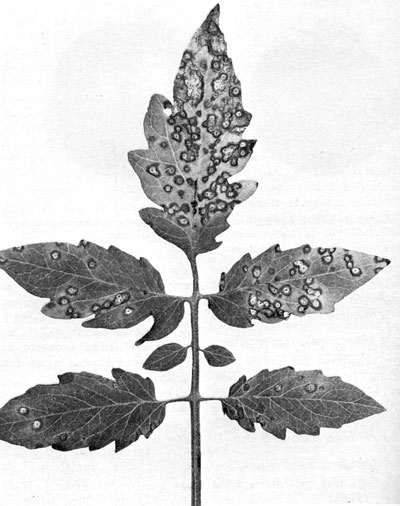

| Septoria leaf spot has small, circular spots that later develop a tan center. Both early blight and septoria leaf spot usually start on the lowest leaves and spread up the plant. Photo from “Tomato Diseases and Their Control,” USDA Agricultural Research Service Agriculture Handbook No. 203, 1972. |

Symptoms

All three of these diseases are primarily foliage diseases. The pictures show that early blight is easily diagnosed by the concentric, target-like rings that form in the leaf lesions. Septoria leaf spot has smaller, more circular spots that later develop a tan center. Both early blight and septoria leaf spot usually start on the lowest leaves and spread up the plant. With early blight, the infected areas of the leaf coalesce, and the whole leaf turns yellow and then dries and falls off. With septoria, the leaf spots become numerous, and infected leaves turn slightly yellow and then brown.

Late blight appears on tomato leaves as pale green, water-soaked spots, often beginning at leaf tips or edges. The circular or irregular leaf lesions often are surrounded by a pale yellowish-green border that merges with healthy tissue. Lesions enlarge rapidly and turn dark brown to purplish-black. During periods of high humidity and leaf wetness, a cottony, white mold usually is visible on lower leaf surfaces at the edges of lesions. In dry weather, infected leaf tissues quickly dry, and the white mold disappears. If you suspect late blight but do not see the symptoms, take a leaf that is infected, put it in a plastic bag, and the cottony white mold will appear.

Fruit rotting from early blight usually comes later in the season and is centered around the stem end of the ripe tomatoes. Late blight develops on green tomato fruit, resulting in large, firm, brown, leathery-appearing lesions, often concentrated on the sides or upper fruit surfaces first, but later taking the whole tomato and turning it into a brown golf ball. If conditions remain moist, abundant white mold will grow on the lesions, and secondary soft-rot bacteria may follow, resulting in a slimy, wet rot of the entire fruit. Septoria leaf spot rarely infects the fruit.

Disease Cycle

Early blight and septoria leaf blight pass dormant periods on any plant debris that has not fully decomposed, including seeds. Initial infection typically occurs from spores produced on the overwintering fungus and splashed onto new tomato plants. Later, spores are produced on any infected tissue and spread by splashing water, wind, machinery and by hand.

Late blight requires a living host between seasons. In the Northeast the potato tuber is usually the only source of inoculum, since tomatoes do not live through our winters. Potatoes that are not harvested and turn into volunteer sprouts, or sprouting tubers in cull piles, are the initial sources of sporangia that can be spread miles in the wind. Such sporangia can live for one to two hours even in the dry sun before landing on new, wet tissue. Germination takes place just a few hours after landing. New spores are later produced on infected tissue. Each lesion can produce 100,000 to 300,000 sporangia that end up blowing in the wind. Under moderate temperatures (60 to 80 degrees) and high humidity, the disease spreads very rapidly.

Control

The first step in controlling these diseases is good sanitation. On a small scale, diseased plants should be removed from the field and destroyed. On a large scale, plow deeply in the fall to bury debris. Sanitation is particularly important for late blight. Cull potatoes must freeze, be crushed or composted or buried at least 2 feet deep in order to eliminate the fungus. In the spring be sure to scout for potato volunteers. If you save your own seed, do not save seed from diseased tomatoes. Buy seed or transplants only from reputable sources.

Don’t let tissue remain wet for prolonged periods; this helps a great deal. Promote good air circulation by orienting the rows in the prevailing wind direction, avoiding wind breaks and controlling weeds. Irrigate early in the morning rather than in the evening so that the plants dry quickly in the sun.

Rotating with crops outside of the tomato family for two years will work if you can control other sources of inoculum. Eliminate non-crop plants in the tomato family that can carry these diseases if you can. These include nightshade, bittersweet, ground cherry, horsenettle and petunia.

Scouting for “hot spots” in fields of otherwise healthy plants and removing diseased leaves may work if you catch things early enough. However, if 5 to 10% of the foliage in the “hot spot” is infected, the disease probably has spread already.

Everyone has favorite tomato varieties, but you can plant some resistant ones as a backup measure. The cultivars ‘Mountain Fresh,’ ‘Mountain Supreme’ and ‘Plum Dandy’ have resistance to early blight. Johnny’s Selected Seeds has two new varieties that are early blight resistant, ‘JTO 99197’ and ‘JTO 99203.’ Oregon State University has released a variety called ‘Legend’ that is somewhat resistant to late blight – at least the disease develops more slowly, so your harvest is longer before the crop goes down. Territorial Seed Company is carrying ‘Legend.’ Johnny’s has a late blight resistant plum tomato called ‘Juliet.’ I do not know of any varieties resistant to septoria leaf spot.

The product Serenade, a natural fungicidal strain of the bacteria Bacillis subtilis, is registered for early and late blight. It works as a foliar spray that then colonizes the leaf surface and keeps the pathogens from geminating. It also outcompetes them for space and food on the leaf. It is being tried this year, and I will report the results by the end of the season.

As a last resort, copper fungicides are permitted in organic production. Because of the inert ingredients, not all brands are allowed. I know of four brands that have been reviewed and approved by OMRI (Organic Material Review Institute) or by the Department of Agriculture in Washington state: Basicop, Champion, COCS WDG from UAP, and NuCop 50 DF. Kocide is not approved. Remember, overuse of copper can lead to excess levels in your soil. MOFGA requires that certified growers who use copper monitor levels with soil tests.

If you need to go the copper route, scout carefully for symptoms and begin sprays at the first signs. Then repeat applications on about a weekly schedule to ensure that new plant tissue is covered.

You can contact Eric with your questions about farming and gardening at [email protected] or by calling the MOFGA office.