Never Let ‘Em Set Seed

Swede Midge

With shortening days and cooling temperatures, lots of annual weeds are registering these environmental cues as a directive to produce as many mature seeds as they possibly can before their time runs out. Andrew Radin at URI recently wrote about each weed plant’s potential contribution to your weed seedbank, annd how you might draw down your weed seedbank, and was kind to let us reprint it here.

Unfortunately it appears that the swede midge, an invasive pest of brassicas, has been found for the first time in Maine. Probable cases were found in both Aroostook and Franklin counties. We may have a few years before the pest’s population builds up enough to be very noticeable around the state, but damage can go from a few funky looking plants the first year or two, to crop failure the next if you don’t recognize the damage and manage proactively. Luckily we are among the last of the New England states to get this pest, so we have others’ experience to draw from.

|

| Amaranth left; barnyard grass right |

|

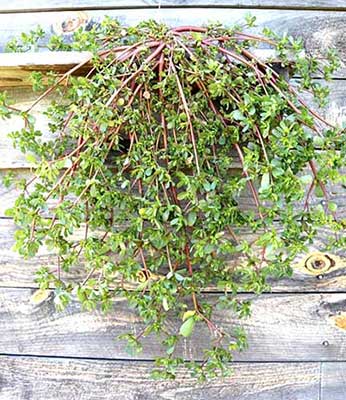

| Purslane |

|

| Chickweed just getting going and already starting to flower |

“NEVER LET ‘EM SET SEED”

By Andrew Radin, University of Rhode Island Extension

At this time of year, most of you are too busy reaping what you intentionally sowed to take control of your maturing weeds. They know this. And they are busy dropping lots of new seeds. For next year. And the year after…

The title above comes from Dr. Robert Norris, retired UC-Davis weed scientist. Early in his career, he studied seed output of individual weed plants. The table below shows some examples. Black Nightshade is appearing on more and more farms. Before you know it, those green berries have mature seeds. Also seeing lots of Oakleaf Goosefoot, which is a sort of micro-Lamb’s Quarters. Foxtail grasses are in their full, seed-dropping glory right now. Seeds of most annual weedy grasses die after two or three years, but some broadleaf seeds can last for decades. Norris claims that, on average, the bulk of your weed seed bank will be depleted after FIVE years of obsessive weed control. And then, of course, you must obsessively maintain that discipline.

If you are looking at serious annual weed problems, year after year, it may make sense to take a patch out of production and grow a heavy duty, weed-smothering cover crop. This is something you would plant in early to mid June, depending on soil temperature. Waiting until the soil is fully warmed is important for two reasons:

1) you will allow a major flush of summer annual seeds to germinate, which you can then erase with a shallow tillage implement like a Perfecta;

2) Your cover crop seed will germinate very fast, outgrowing the weeds.

Good options are buckwheat, Japanese millet, Sorghum X Sudangrass, and forage varieties of cowpea and soybean. Cover crop seed isn’t free, but neither is the time and space you decide to set aside to grow a good cover. Don’t skimp on seed, particularly if you are only setting aside a 1/2 acre-solid cover is the goal. The worst that excessively high seeding rate can do is waste a little money for no added benefit, except the peace of mind that you won’t have bare patches that fill in with weeds- and that’s actually a big benefit. So go for the high end of the recommended rate.

Remember, also, that cover crops are plants that require nutrients, just like the crops that we harvest.

While cover crops are often used to “mop up” excess nutrients to make them available to the next crop, the object of a smothering summer cover crop is to produce a cover that is impenetrable to sunlight so that annual weeds can’t grow up enough to produce seed. So fertilize- just 40 to 50 lbs of N/acre for grasses. If growing legumes, INOCULATE!

Sometimes, it makes sense to intensify your vegetable production on a smaller space while improving some other patches of ground.

|

| Blind head of broccoli; characteristic damage of swede midge |

|

| Cauliflower with swede midge damage |

SWEDE MIDGE (Contarinia nasturtii)

The swede midge is a relatively new invasive pest that has been spreading south and east from where it was first found in Canada in 2000. These tiny midges are weak fliers, but they can do a lot of damage to brassica crops when they get established and their populations build up. Adults lay their eggs near the growth points of brassica crops and the hatched larvae (maggots) feed on the growing tip of the plant. Because of this, damage is most severe in heading crops (broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, etc).

This midge is very small and hard to find, tucked away in the plant’s growth point. That means that scarring and warped growth from earlier feeding is likely to be the first indication you will find of this new invader. The feeding damage can disfigure new leaf growth, and as few as one individual at the wrong time can cause total loss of the primary saleable portion of heading crops.

After feeding on the plants, larvae then drop to the top layers of the soil to pupate, and later emerge as adults to repeat the cycle on other plants.

Because the larvae are the only stage in the life cycle to damage the plant, people often do not notice the damage until the swede midge larvae have already left the plant. Damage to the apical meristem (the growth point where broccoli heads, etc, are eventually formed) is irreversible. Side shoots often develop their own small heads after damage to the apical meristem.

Because of the nature of the damage, the nature of different crop architecture, as well as some crop preference on behalf of the midges, some crops are better suited for tolerating swede midge damage than others. Most susceptible are broccoli, cauliflower, collards and kohlrabi. Least susceptible are turnips and greens like bok choi or mizuna. In the middle of that range is cabbage, brussels sprouts, and kales. Anecdotally, ‘Red Russian’ kale types seem to be the most susceptible, while ‘Lacinato’ types (aka ‘Toscano’, ‘Dinosaur Kale’) seem to be the least susceptible.

If you notice swede midge damage in your fall brassicas, it may be prudent to assume that there will be pupae overwintering in that soil.

Organic control options are limited – the protection of the plant’s overlapping leaves around the growing point shield swede midge from insecticides that would otherwise kill it, and row cover or exclusion netting is effective only if the midge are not already present in the soil as overwintered pupae.

Elisabeth Hodgdon at Cornell Cooperative Extension reports that some farm trials found good protection with regular sprays of spinosad (Entrust) and kaolin clay (Surround) under a 2ee label in New York, but only when swede midge populations were small. With large populations, no OMRI listed products were found to be effective. If hoping to pursue a spray program for control, check material label instructions carefully (the label is the law), and clarify with the Maine Board of Pesticides Control if you have any questions.

The best recommendations as of now aren’t drastically different than what many farmers currently do: utilizing exclusion, starting at transplanting or direct seeding (row cover or netting like 25g ProtekNet), combined with crop rotations that are as long and distant as possible (3+ years and ideally more than 1,000 feet apart – over half a mile is best). Swede midge can also survive and reproduce on brassica weeds (yellow rocket, wild mustard, pennycress, shepherd’s purse, etc.), so brassica weed presence should also be taken into account for each field being utilized in a rotation.

Some other management options being explored are pheromone mating disruption (confusing male adults with large doses of pheromones), essential oil products like Garlic Barrier which has shown marginal efficacy, and tarping over infested ground, which may prevent overwintered midges from successfully emerging as adults.

Please feel encouraged to send photos of unexplained damage in your brassica crops, especially if you are located closer to our borders.

More information and photos can be found here.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under subaward number ONE19-334.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.