|

| Shadbush blossoms (Amelanchier). Kerry Hardy photo. |

One Tree-Hugger’s Opinion

by Kerry Hardy

It’s hard not to notice the foliage on our beautiful native trees at this time of year, and it’s worth remembering that “the spring of the leaf” in May and “the fall of the leaf” in October are the sources of those seasons’ names. In fact, fall is the perfect time to familiarize yourself with our native hardwoods, because in the span of a month you can see the whole suite of identifying features: leaf shape, fall color, mature fruit and finally bare bark, winter twigs and the distinctive silhouette of each species.

My interest in the subject goes way back to a childhood spent climbing trees and rambling the woods of Lincolnville, and my working life – both as a landscape designer and as a writer studying Maine’s Indians – has only deepened my appreciation of the beauty and utility of our native trees. In short, some of the nicest people I know are trees.

Being asked to write an article about some of my favorites was a mixed blessing: I love talking about them, but I hate to try to choose favorites – so rather, let me just say that the following trees are all very worthy additions to any landscape that can give them the soils, sun, water and elbow room that they need.

Moreover, these are species that I think are under-appreciated; they should all be better known and utilized more often. Most of us know a white pine, red oak, sugar maple or paper birch when we see it, but the trees on this list are all worth getting to know as well. Each brings its own gift to the landscape, whether it be flowers, fruit, medicine, wildlife habitat or simply its own personality.

|

| Shadbush fruit (Amelanchier). Kerry Hardy photo. |

Small Trees

Desirable small trees include striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum), shadbush (Amelanchier laevis), mountain ash (Pyrus/Sorbus americana and decora) and chokecherry (Prunus virginiana).

Striped maple, perhaps better known in Maine as moosewood, can grow to be as tall as 50 feet, but most seldom exceed thirty. It grows happily in the shade of taller trees, and arranges its branches and huge leaves to best catch whatever sunlight trickles through the canopy above. Chipmunks and deer mice are fond of its fleshy winged seeds, or samaras, and will fill their storehouses with them. When the Ice Storm of ’98 ripped holes in the forests of central Maine, untold thousands of moosewood sprouts erupted and have now formed almost impenetrable thickets. Here, safe from all predators, deer and moose can nap lazily on fall afternoons, rising occasionally to polish their antlers on the trees’ smooth green stems. In addition to its value to wildlife, I like this tree for its ornamental value: distinctively striped bark, red winter twigs and golden fall color. If you can plant a young tree at the edge of a woods and give it a bit more sunlight, you’ll see it at its best.

Shadbush, Juneberry, wild pear, sugar pear, serviceberry – these are just some of the common names applied to members of the Amelanchier genus. My personal favorite is the downy serviceberry, Amelanchier laevis, which combines pure white flowers and bronzy-red spring foliage to light up the landscape in early May. By mid-July, songbirds are eagerly seeking its succulent fruit – and so am I. The hiking trails on the backside of Monhegan Island are loaded with thousands of shadbush, and it seems to make better fruit there than it does on the mainland. Come fall, the leaves will turn yellow, orange and even blazing red; and even in the winter its smooth silver bark remains very attractive. All in all, I think it’s our finest native ornamental, and it can be found in many nurseries around the state.

|

| Downy serviceberry at the water’s edge is a spring treat. Kerry Hardy photo. |

If you visit Monhegan to see the shadbush, you might also notice the American mountain ash, which also thrives on that island. Along the coast, mountain ash is usually multi-stemmed and seldom exceeds 30 feet; on our mountains, it grows to the very limit of timberline and is even smaller. However, in some parts of the state (especially Aroostook County), a slightly different form, sometimes called Sorbus decora, grows to a much statelier single-trunked form, similar to the Rowan-trees of Scotland. Flowers, fruit and fall color are all striking in mountain ash, and its Wabanaki name of makwamin (“bear’s berry”) hints at its value to wildlife.

Chokecherry is one of many representatives of the Prunus genus in Maine, and I think it’s vastly underutilized as a food plant. Each autumn we all drive by tons and tons of roadside chokecherries, but only the songbirds seem to know what good food it is. Most of us have childhood memories of its mouth-puckering astringency, but if you parboil the berries and run them through a Foley-type food mill, all the bitterness is left behind and a wonderful cherry sauce is the result. Further cooking and sweetening makes this into a jam that belongs in every Maine pantry.

Large Trees

Some favorite large trees are basswood (Tilia americana), yellow birch (Betula lutea/allegheniensis), bur and white oak (Quercus macrocarpa and Q. alba/bicolor) and bigtooth aspen (Populus grandidentata).

|

| Yellow birch bark can be golden, coppery or silvery, and often exfoliates in tight curls like these. Kerry Hardy photo. |

Basswood and yellow birch thrive in the same sweet soils that sugar maples prefer, and interestingly enough you can make syrup from these two species as well – if you have the patience to reduce 60 or more gallons of sap for each gallon of syrup. Personally, I’m content to take the word of others on this point; I’d rather just plant them because I like their looks. I find yellow birch to be every bit as handsome as paper birch, especially when it grows at elevation and becomes noticeably more silvery in appearance. Basswood also has a long pedigree of utility to man, for its inner bark produces long, strong fibers – the wicopy used for rope by woodland Indians across North America, and the line hidden in its other name, linden – and its soft wood was easily worked into dugout boats long ago. As for wildlife, if you have a basswood tree, you’ll probably also have some yellow-bellied sapsuckers as visitors, and honeybees as well, lured by the basswood’s sap and nectar. Both basswood and yellow birch usually have a dull gold fall color, although the birch sometimes approaches a clearer orange. If you’re ever in doubt about the identity of a yellow birch, just bruise a twig – the clear smell of wintergreen oil will be unmistakable.

Bur oak and white oak are the equivalent of first cousins, or maybe even siblings, in the Quercus genus. Their nut meats are noticeably sweeter than those of red oak, which made them preferred foods of the Native Americans in pre-contact times. There are thousands of bur oak along the Sebasticook River in central Maine, and their density in this river corridor makes one suspect that human transport may well have played a part in their pattern of distribution. When Champlain and other European explorers first went ashore along the coast here, they all saw the same kind of landscape; a grassy savannah with freestanding giant oaks. This was the result of burning by Indians, which killed off thin-barked trees such as beech and maple but favored the thicker-barked oaks. Like all nut trees, oaks are tap-rooted – so dig them young, or not at all.

|

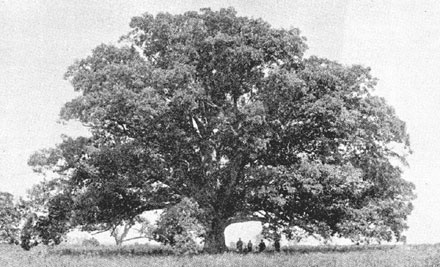

| White oaks can live 500 years or more and spread over a quarter acre. |

Bur oak is ordinary enough in its appearance, but I think white oak is the aristocrat of the whole oak family, with its light gray bark, broad-spreading branches, pinkish fall color and tawny leaves that refuse to drop off until the next growing season begins. Sadly, its value as lumber for boatbuilding and home heating led to its near-extirpation around the state, just as the 19th century demand for wintergreen oil once wrought havoc with the numbers of yellow birch across this region.

Bigtooth aspen is a tree that I love simply for its foliage. Like its cousin the trembling aspen, or “popple,” bigtooth aspen can spread by underground stolons to form a pure stand of trees that are all one organism. This habit can create memorable patches of color on late October hillsides, when almost every other deciduous tree has already given up the ghost. I think of it as the silver and gold of the forest – silver in late May and early June as its new leaves unfold, and then gold late in the fall, when the ground under every tree is littered with leaves looking like fallen doubloons. We think of aspen as being a soft-wooded and short-lived tree, but bigtooth aspens can grow to a surprising age and size – the state champion, a tree in Appleton, is fully 12 feet in circumference, and 8- to 10-footers are fairly common around the state. As it ages, the trunk of a bigtooth aspen looks more and more like that of a red oak, and more than once I’ve been surprised to look up and see that the “oak” I’m admiring is really an aspen.

|

| Bigtooth aspens’ silvery leaves seem almost like blossoms on this spring hillside. Kerry Hardy photo. |

Finding and Growing Trees

As you drive or hike around the state this fall and next spring, keep an eye out for these noteworthy natives. More power to you if you can find them in a garden center, but you’re more likely to get them by taking your shovel or trowel and going “shopping” in the woods – with the landowner’s permission. Many are also listed in the Fedco Trees catalog. None of these species could remotely be called rare – but if you can give them what they need to grow, they will bring a rare beauty to your property.

About the author: Kerry Hardy is a landscape designer and writer living in Rockland, Maine. He formerly served as director of Merryspring Nature Center in Camden and Rockport, and is currently collaborating in the development of Farmers Fare in Rockport. He is also the author of Notes on a Lost Flute – A Field Guide to the Wabanaki (Down East, 2009), reviewed in this issue of The MOF&G.