by Joyce White

Many people first visit Hedgehog Hill Farm for the widely advertised, free “Sundays in the Garden at 2.” Every Sunday afternoon from mid-June through August, the public is invited to stroll through the lush gardens and hear a lecture about some aspect of gardening at the 200-acre farm in the small, western Maine town of Sumner.

Farm owner Mark Silber might discuss methods of growing vegetables from seedlings started in greenhouses, use of mulch, growing herbs for fresh use, preserving herbs, growing berries, saving seeds, growing flowers for cutting, or growing flowering plants for drying and arranging. Then he takes participants on a tour of the gardens, highlighting that day’s discussion topic.

Being a serious and successful farmer doesn’t preclude a sense of humor and humility. On a Sunday when Mark was discussing growing grapes and berries, with visitors seated in a sturdy and beautiful arbor covered with ripening ‘Concord’ grapes, he described how the arbor came about: He had unwisely ignored his father’s advice when building the first one and, when it was fully loaded with ripening fruit, a strong wind toppled it.

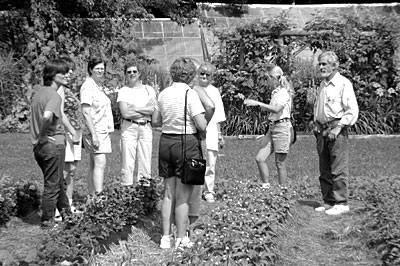

|

| Mark Silber (right, in front of a grape arbor) conducts a tour of his farm. His tours and lectures are well known for the amount of horticultural information imparted. Photo courtesy of Mark Silber. |

The replacement is well built from 12-foot cedar logs with seating along both sides and is attractive as well as functional. The ‘Concords’ are planted at 4-foot intervals and are fertilized with horse manure. Cow manure would do as well, Silber says, but with three horses, horse manure is what’s available. Watering well the first year is of prime importance in helping grapes establish the roots that will provide for many healthy crops. Runners must be pruned off the first year too, so that each plant will establish a very strong stem. Some pruning is necessary every spring thereafter, and the vines may need a little training to climb the arbor.

Birds aren’t much of a nuisance with grapes, he says, because they’re usually preoccupied with preparations to migrate about the time the grapes ripen. Raccoons, though, are another matter. When the vines were heavy with the nearly ripe fruit of his first crop, Silber admired their lushness and planned to harvest them the next day. But the next morning all that lushness lay on the ground, just a layer of flat skins left by the overnight coon raid. Now he covers them with shade cloth about a week before they are fully ripe.

The ‘Concord’ variety covering this arbor ripens late, and the shade cloth also helps prevent frost damage. Mark guided the group to his newest arbor and a new variety, ‘Canadice,’ which ripens earlier and is sweeter but smaller. Japanese beetles are about the only problem he has with grapes; they are hand picked into soapy water.

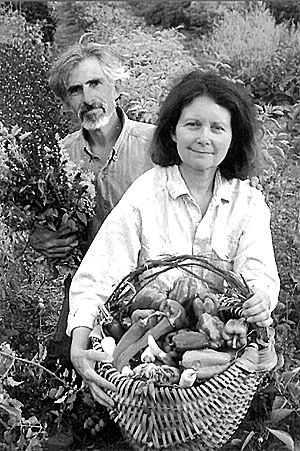

|

| Mark and Terry Silber built their successful farm over some 25 years and documented their lives and farming and gardening practices in their books. Last year Terry succumbed to cancer. Photo courtesy of Mark Silber. |

In addition to weekly lectures, Hedgehog Hill offers hands-on, daylong workshops about such topics as “Gardening with Perennials” or “Creating a Dried Flower Wreath.”

A Quarter Century Documented

Silber, now sole owner of the farm, says that sharing knowledge about living responsibly on the land has always been an integral part of the farm plan. His wife, Terry, had been an active partner in all aspects of the farm until her illness and death from cancer in July 2003. “Our concept of the farm,” Silber explains, “was that we’d always be running it together. We worked 365 days a year.”

His only full-time, year-round help now is Cathy Lee, who has been with Hedgehog Hill for more than 20 years. Silber describes her as an “amazing woman – strong, diligent and loyal. I wouldn’t have been able do it without her.” Much of the seasonal work gets done through a system that is not quite apprenticeship, not exactly volunteer, but a sort of barter system.

Before making the farm their full-time occupation and residence in 1978, the Silbers were living in Boston and coming to their place in Maine only for weekends. Terry, who grew up in Lewiston, heard about the 1837 Greek Revival farmhouse with 40 acres from her mother. She bought the house at the end of a dirt road for a weekend retreat in 1965 for 5000 dollars. She continued working in Boston for publications, in 1971 becoming art director at The Atlantic Monthly.

Mark had studied photography since the age of nine, and he met Terry when he was selling his photographs while a student at Harvard. He had left samples for the art director – Terry, who was working at Harvard Magazine – to consider. She commented that his photographs looked like Russian landscapes, and he explained that he was born in the Ukraine. His father was a Polish citizen and had been captured first by the Germans, then by the Russians in W.W.II. The family emigrated to the United States in 1944, when Mark was thirteen.

Silber’s photography brought the couple together and continued to be one of the important strands weaving through their 25 years together at Hedgehog Hill Farm. Growing plants organically and living sustainably were central to their life on the farm. They combined Mark’s photographic and Terry’s literary skills to create books illustrating their experience for others.

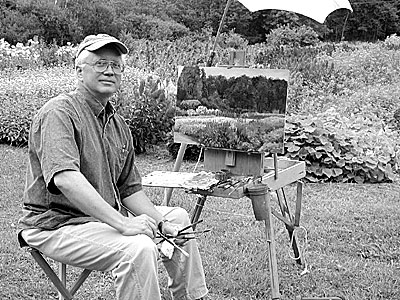

|

| Artist Joel Babb paints the garden at Hedgehog Hill Farm. Photo courtesy of Mark Silber. |

In Growing Herbs and Vegetables from Seed to Harvest, published in 1999, the Silbers share their knowledge about selecting seeds and plants, transplanting, controlling pests, harvesting and storing the harvest, and saving seeds. They used sidebars and charts as well as color photos throughout the book.

“We wanted people to know how to collect seeds and grow their own vegetables so they won’t be dependent upon a few large corporations,” says Silber. “I’ve been saving our own seed for 25 years for many varieties.” They gave up on corn since writing the book, though, because coons eventually got into the corn patch, despite electric fencing.

The book took about seven years to complete, with most of the writing and research done in winter and photography in summer. “I keep scrupulous notes,” remarks Silber. The shop is closed during January and February, providing time to work on books, the plant catalog and newsletters.

Terry’s book, A Small Farm in Maine, came out in 1988 and described their experiences with the farm and life in a small town. It became a must-read for city dwellers dreaming of the rural life for themselves.

That same year, The Complete Book of Everlastings: Growing, Drying and Designing with Dried Flowers, with its abundance of lush illustrations, put Hedgehog Hill Farm even more firmly “on the map.” This seminal book on dried flowers drew on their combined knowledge and skills in horticulture, Mark’s expertise in photography and Terry’s knowledge of writing and design. “Nothing as accurate has yet been done,” Mark says. “We’re still getting letters from readers saying how useful it is. Some even call it their bible.”

A lot of hard work and trial-and-error preceded their present luxuriant gardens, splendid books and attractive home and shop. First, they’d jacked up the old house, which had been abandoned for a dozen years. Never mind that neither he nor Terry had previous, hands-on building skills. His father helped some, and Mark knew some building basics. They gutted and rebuilt the house “from scratch,” studying books about building as they went and asking for advice when necessary.

“Terry and I built the shop with the help of one other person. We did everything ourselves, even the plumbing and electricity. Terry learned to cut and drill. I gave her a drill for her birthday that year,” he remembers with a smile.

Their son, Jacob, was not quite four in 1978, when they moved to Sumner. He liked living in the woods and, though he missed the company of other children, “he became very creative and outgoing, able to converse and play with anyone. He became quite trusting and charming as a result of having a truly heterogeneous community in Sumner.

Starting in 1972, even before they moved permanently in 1978, they gardened and sold vegetables on weekends. They began with 5000 broccoli plants, lots of cabbage, 2000 pepper plants, 200 tomatoes, plus peas, beans, corn and potatoes. From 1973 until 1985, they sold vegetables to restaurants in Portland and at farmers’ markets. Arby’s always took their herbs. They made $498.43 the first year they sold vegetables from the back of a Chevy truck.

They did it all organically and still do. “We used to buy a 50-yard dump truck load of hen manure from DeCosta egg farms and we’d load it into a box on the back of the tractor to fertilize the gardens.” That 1946 Farmall Super A tractor is still in use. They bought it in 1976, and that’s when Silber learned to weld. “That was my first welding job. In some ways, it’s a scourge to know how to do everything, because then you never ask anyone else to do anything. But if you’re running a small farm, you need to be able to do everything.”

Their nearly 200-acre farm (the added to the original 40 acres by buying contiguous pieces as they became available) is mostly wooded, with 6 tillable acres. In keeping with their ideal of minimizing the use of machinery, they have kept the space for growing crops small. Even the tiller, a 1976 Troy-Bilt that has been rebuilt three times and gone through four engines, is used as little as possible. Extensive mulching with straw, grass clippings, wood chips and black plastic reduces the need for cultivation and watering. Once plants get established, they don’t need to be watered, Mark explains, and his well wouldn’t support irrigation, anyway. The mulch is removed every year to work and fertilize the soil; this keeps the soil aerated and helps it retain moisture. They stopped using imported hen manure once they got their own horses; fertility now comes from horse manure, leaves and rotten hay mulch.

|

| The farm crew sets out transplants through plastic mulch. Photo courtesy of Mark Silber. |

Crops are rotated, and small plots of herbs, flowers, vegetables and berries are interplanted to minimize insect problems: “It confuses their GPS systems,” Silber comments.

The Switch to Flowers

After a few years, growing and marketing vegetables “just wasn’t that interesting,” Silber continues. They gravitated toward flowers because of the added variety, to learn new things, because flowers are easier to lift and move, and because the chance of a total crop failure is lower. “If one kind of flower fails one year, we usually have enough stored to get through a substantial period of time. Dried flowers aren’t as perishable as vegetables.”

Growing flowers opened another market, that of providing flowers for special occasions, and it opened a whole new area of learning and teaching. As they experimented with everlastings, always trying new varieties, they added the use of dried flowers in wreaths and other arrangements to their workshop offerings.

Their gardens are orderly, spacious and sumptuous, food for body and soul. Inside the shop, one is enveloped in beauty, in an extravagant intensity of colors, textures and smells. Dried flowers fill baskets and vases, hang in colorful bunches from rafters, adorn walls in wreaths of all sizes.

Each year now, thousands visit Hedgehog Hill Farm to buy plants and seedlings, cut flowers, dried flower arrangements, books and to attend workshops. Visitors are always invited to walk around the farm and to absorb a little of the beauty and serenity of the place.

Part of Hedgehog Hill’s success can be attributed to hard work and attention to detail, the Silbers’ willingness to experiment, and accurate record keeping about plant varieties and rotations. Mark gives a lot of credit to local people who shared their knowledge about gardening in that particular environment with them, as well as to Cooperative Extension and MOFGA – especially Eric Sideman, MOFGA’s director of technical services.

In the community, Mark served over 20 years on the board of selectmen and the school board. He and Terry headed Sumner’s bicentennial celebration, and their fourth book, an award winning photo documentary, grew out of that experience. Entitled Sumner 2000, it features local people, places, scenes and events, and reflects Mark’s background as an anthropologist. (He has a Ph.D. in Medical Anthropology.) Mark was also instrumental in getting a local recycling center started.

Mark explains that at Hedgehog Hill, “We don’t try to convert people, don’t proselytize, but we have always wanted to share knowledge.” The farm was probably the first in Maine to integrate education through farm visits, lectures, workshops and books.

Hedgehog Hill puts out a newsletter nearly every month and a catalog in spring of plants and seedlings for sale. Terry used to do the writing and design, while Mark did layout. Mark now does all three but says it’s a struggle, partly because he didn’t learn English until he came to this county at 13, and his native language uses a different syntax.

Enduring Values

Just as they lived their lives on the farm with ingenuity, integrity and self-sufficiency, they handled Terry’s illness and death with the same values. “From the most basic stuff to the most emotionally draining stuff, we’ve done it,” says Mark. “It’s important to do it yourself.”

He took care of Terry at home and held her in his arms during her last moments. In his meticulous way, Mark researched Maine law governing end-of-life details before deciding against using a funeral home. “Jacob and I made a simple wooden coffin,” and they transported the body themselves to be cremated. Terry’s ashes were scattered over the farm overlooking the mountains.

Mark Silber can be reached at 54 Hedgehog Hill Road, Sumner ME 04292; 207-388-2341; www.HedgehogHillFarm.com.