August 14, 2020

With the hot sunny summer we’re having (please rain…), winter squash development has progressed quickly for many. Make sure that your squash is truly ready for harvest to ensure peak flavor, thanks to the research of Brent Loy, who sadly, recently passed away. One caveat that isn’t mentioned in the squash entry below, is that severe defoliation from powdery mildew necessitates that squash be harvested to salvage what can be saved from the fate of sun scald injury or simply poor flavor. i.e., without leaves, there’s no sugar production to continue improving fruit.

Now is also the time of the year to start doing favors for your “future self.” Shortening days often trigger weeds to put every last bit of energy they have into setting seed. I know that the crabgrass is starting to go wild around my yard and garden. The more seed you can prevent from entering the soil’s “weed seed bank” – the less weeds you’ll have to deal with in the future!

Winter Squash Looks Ready, Should I Harvest?

“Never Let ’em Set Seed”

WINTER SQUASH LOOKS READY, SHOULD I HARVEST?

By Eric Sideman

Winter squash look ready to harvest before they actually are mature. It is important to wait for maturity to have maximum storage and best eating quality. Most squash varieties reach full size by 20 days after fruit set. Accumulation of starch and other dry matter peaks at about 30-35 days after fruit set. But, the fruit is not fully mature until the seeds are fully developed, which occurs about 55 days for butternut. This is different for other varieties. If you would like to read more, take a look at this article by Brent Loy, the very well known plant breeder at the University of New Hampshire. Or, here is a summary put together by the folks at Johnny’s Selected Seeds.

Harvest and Storage

A critical factor in eating quality is maturity of the squash when it is harvested. Most small varieties reach full size by 20 days after fruit set. Accumulation of dry matter and starch content peaks at 30 to 35 days after pollination. However, the fruit is not mature until the seeds are fully developed, which occurs about 55 days after fruit set.

Dr. Loy stresses the importance of maintaining healthy plants until at least 50 days after fruit set because photosynthesis is essential to the development of sugars and dry matter. A squash that is picked too early will continue to develop seeds, but it does so by depleting the dry matter, thereby reducing eating quality.

Although fruit and seed maturity are similar across the three main species of edible winter squashes and pumpkins, harvest and storage recommendations vary by type.

Cucurbita maxima | Kabocha, Hubbard, and Buttercup Squashes

Kabocha, hubbard, and buttercup (C. maxima) varieties should be harvested before complete seed maturation, at about 40 to 45 days after fruit set, when the fruit is still bright. That’s when the rind is hardest, so less likely to be damaged in storage. They also are susceptible to sunburn as the vines die down, so it’s best to get them harvested and out of direct sun before then to prevent the rind from turning brown or, with extreme sunburn, white. Kabocha squash have a high dry matter content and small seed cavity, so seed maturation off the vine is not a problem. However, once harvested, they should be stored at room temperature for 10 to 20 days to allow sugars to reach acceptable levels.

C. pepo | Acorn Squash, most Pie Pumpkins

Acorn squash (C. pepo) are misleading because they reach full size and develop a dark green-to-black mature color about two weeks after fruit set – 40 to 50 days before they should be harvested. Dr. Loy says that a better way to judge maturity is to look at the rind where it touches the ground. Immature squash have a light green or light yellow ground color, whereas mature squash have a dark orange ground color. Immature acorn squash have low sugar levels and although they will develop sweetness after harvest, they do so by depleting the dry starchy matter to convert it to sugars. This means storage life is shortened and eating quality declines.

C. moschata | Butternut Squash, some Pie Pumpkins

Butternut squash (C. moschata) are easier to judge by sight because they don’t acquire their characteristic tan color until late in development, 35 days or more after fruit set. If the weather stays frost-free, they should be allowed to remain on the plants until 55 days after fruit set. In short-season areas, they often are harvested soon after turning tan because of the risk of frost damage. At that point, however, the sugars have not elevated to the 11% required for good flavor, so butternut squash harvested at 55 days after fruit set should be stored for 60 days at 56-60°F/10-16°C, with relative humidity between 50 and 70%. Carotenoid content also increases in storage, making the butternut squash more nutritious after it’s been stored for a couple of months. To accelerate maturity and increase sweetness, Dr. Loy has found that butternuts held at warm temperatures (up to 85°F/29°C) for two weeks develop acceptable levels of sugars.

|

| Amaranth left, barnyard grass right |

|

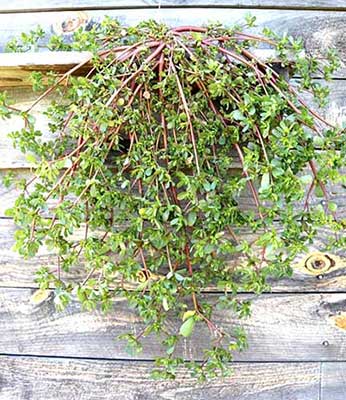

| Purslane |

|

| Chickweed just getting going and already starting to flower |

“NEVER LET ‘EM SET SEED”

By Andrew Radin, University of Rhode Island Extension

At this time of year, most of you are too busy reaping what you intentionally sowed to take control of your maturing weeds. They know this. And they are busy dropping lots of new seeds. For next year. And the year after…

The title above comes from Dr. Robert Norris, retired UC-Davis weed scientist. Early in his career, he studied seed output of individual weed plants. The table below shows some examples. Black Nightshade is appearing on more and more farms. Before you know it, those green berries have mature seeds. Also seeing lots of Oakleaf Goosefoot, which is a sort of micro-Lamb’s Quarters. Foxtail grasses are in their full, seed-dropping glory right now. Seeds of most annual weedy grasses die after two or three years, but some broadleaf seeds can last for decades. Norris claims that, on average, the bulk of your weed seed bank will be depleted after FIVE years of obsessive weed control. And then, of course, you must obsessively maintain that discipline.

If you are looking at serious annual weed problems, year after year, it may make sense to take a patch out of production and grow a heavy duty, weed-smothering cover crop. This is something you would plant in early to mid June, depending on soil temperature. Waiting until the soil is fully warmed is important for two reasons:

1) you will allow a major flush of summer annual seeds to germinate, which you can then erase with a shallow tillage implement like a Perfecta;

2) Your cover crop seed will germinate very fast, outgrowing the weeds.

Good options are buckwheat, Japanese millet, Sorghum X Sudangrass, and forage varieties of cowpea and soybean. Cover crop seed isn’t free, but neither is the timeand space you decide to set aside to grow a good cover. Don’t skimp on seed, particularly if you are only setting aside a 1/2 acre-solid cover is the goal. The worst that excessively high seeding rate can do is waste a little money for no added benefit, except the peace of mind that you won’t have bare patches that fill in with weeds- and that’s actually a big benefit. So go for the high end of the recommended rate.

Remember, also, that cover crops are plants that require nutrients, just like the crops that we harvest.

While cover crops are often used to “mop up” excess nutrients to make them available to the next crop, the object of a smothering summer cover crop is to produce a cover that is impenetrable to sunlight so that annual weeds can’t grow up enough to produce seed. So fertilize – just 40 to 50 lbs of N/acre for grasses. If growing legumes, INOCULATE!

Sometimes, it makes sense to intensify your vegetable production on a smaller space while improving some other patches of ground.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under subaward number ONE19-334.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.