By Anson Biller

The appearance of the first taproots of our future chestnut trees emerging from their shells was a pivotal moment at Full Fork Farm in China, Maine. Never mind that I was observing them after the seeds had sat in plastic bags in a walk-in cooler for four months. This was big: The emergence marked the beginning of the 6-acre orchard that will bear and provide nut crops well beyond our own lifetimes. At maturity, the orchard should produce 12,000 to 18,000 pounds of nuts per year.

Beginning in 2020 Full Fork Farm undertook a two-year project funded by the USDA’s Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) Farmer Grant Program to study the effect nursery container depth has on chestnut seedling growth and how those differences translated to first-year establishment in the field.

Fostering healthy root systems is important to ensuring plant success. It can mean the difference between summer and winter abundance or crop failure, and is all the more important for perennials that live with the effects of their initial growing conditions for years. Chestnuts are a taprooting tree species. Their survival strategy is to send that first probing root as deep into the soil as possible. That root anchors the tree, avoids shallower root competition and taps into groundwater reserves.

What are the implications for nursery culture given this natural habit and for the farmer wanting to establish a thriving orchard? In a time when climate change continues to bring increasing weather extremes to Maine, can a small change in container depth play a role in producing perennials better suited to weather these challenges?

I will admit outright that continued research is needed to assess long-term growth, but Full Fork Farm found interesting results through our SARE grant that are informing how we will propagate perennials to expand our you-pick operation going forward.

The Experiment

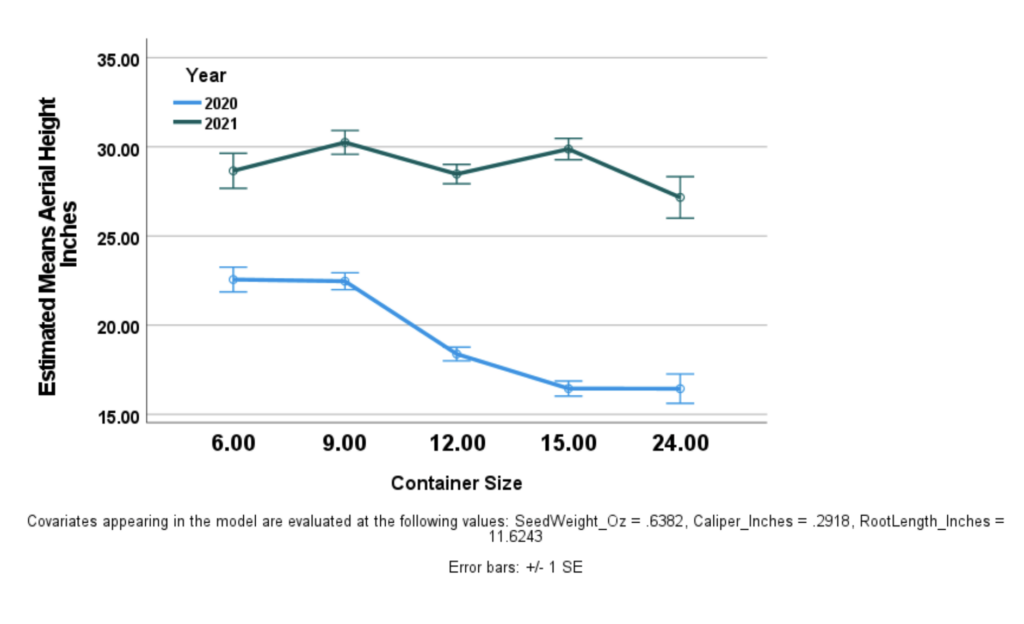

We separated chestnut seeds into five experimental container depths (6, 9, 12, 15 and 24 inches) with 128 seeds per group. At a depth of 24 inches, we sought to create conditions where taproot growth would be uninhibited.

Seeds were sown into ShellT grow tubes and held together in bulb crates. This novel approach is certainly worth repeating in future years, and one we have adopted for our tomato production. While the tubes provided a uniform width for our experiment, they also prevented root-binding by means of air pruning. Additionally, the concept that one’s nursery pot can then become its initial field protection against deer and wind is compelling for reducing establishment costs.

Seedlings stayed in a nursery zone with overhead irrigation for the duration of their first year and were then stored bareroot in our walk-in for data measurement over the winter (aerial growth, root length and caliper). A subset of the healthiest trees was selected from each group and transplanted in the spring of 2021 with the help of volunteers. Data was collected again in the fall following dormancy.

Results and Discussion

We found that a shallower container produced significantly more aerial growth in the nursery year (the 6- and 9-inch groups grew approximately 4 inches more than the 12-inch group, and roughly 6 inches more than the 15- and 24-inch groups). This advantage did not, however, carry over to the field year. All experimental groups were roughly the same height this past autumn, which means that once in the field the 12- and 24-inch groups grew at almost double the rate of the 6- and 9-inch groups. The greatest gain was made by the 15-inch group, averaging 2.96 inches more growth than the 12-inch group. If this trend continues, the 15-inch group will average a foot taller than their 12-inch counterparts by their first anticipated year of bearing. The difference 3 inches of soil depth can have — at 20 cents additional cost per tree, in our case — may be substantial.

The taproot of a chestnut emerging from its shell.

Conclusive results remain to be seen. Perhaps the trees in the 6- and 9-inch groups focused energy on expanding their limited root systems during their first year in the field, and will now grow at a similar rate as the other groups this season. Perhaps the 24-inch group will gain an advantage over time by virtue of a deeper root system. Time is needed to answer important questions related to survivorship, years to bearing and overall health. As of February 2022, our field planting is at 98.3% survival with only a single tree in each group dying (this number may change after their first winter).

Current data suggests that 15-inch containers provide the most vigorous chestnut seedlings. That said, logistical concerns regarding equipment need consideration. If using a spade, every 3 inches deeper one digs requires quite a bit more work. With additional soil, crates of nursery plants grow harder to manipulate. You might find me in the field sowing seeds directly if it is shown that uninhibited taproot growth grew the superior tree, but I certainly wouldn’t attempt growing in 24-inch-deep containers again. This is to say, the 12-inch containers produced a fine seedling that I would be satisfied to plant, at present, if faced with equipment or financial constraints.

The difference container size makes for long-term establishment requires further inquiry. Which experimental groups will be thriving three years from now when the trees first begin to bear? Which will survive the increasingly harsh conditions we are experiencing due to climate change? Which of these trees, mere seeds in our walk-in two years ago, will our farm ultimately leave behind to feed future generations for 100-plus years to come?

You can find a detailed report of our SARE grant (project number FNE20-947), including photos of root systems, projects.sare.org. We anticipate being able to include chestnuts within our you-pick offerings and for wholesale by 2025-2026. Feel free to reach out with questions or inquiries at [email protected]. We are particularly interested in considering collaboration for shared equipment related to chestnut processing.

This article was originally published in the summer 2022 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.