|

By Diane Schivera, M.A.T.

Want to save money and feed your animals well at the same time?

On most farms the biggest cost for keeping livestock is feed. The quality of the feed can seriously impact the health and production of livestock. For ruminant animals, most if not all of their feed will come from forages in the form of hay, balage, haylage or silage. Learning to select quality forages to feed your animals is a valuable tool.

This article focuses primarily on hay, but when reading a forage analysis, the same principles will hold for balage, silage or haylage.

First, simply look at your hay. It should be nice and green and not full of stems. The nutritional value (energy and protein) of hay is in the leaf, so the more leaf and the more green leaf in the hay, the better the quality. If hay is beige, it was likely rained upon. If it is chocolate, it likely heated up too much – the result of being baled too moist or being rained on after being baled. Both lower the quality of hay.

Next, break open the bale. It should smell good and remind you of a summer day. It should not be dusty or moldy; animals don’t like to eat dusty hay, and mold spores can sicken animals (and humans – so don’t smell hay if you suspect it’s moldy). If you lay the hay out and grayish white particles fall out, those are mold spores.

|

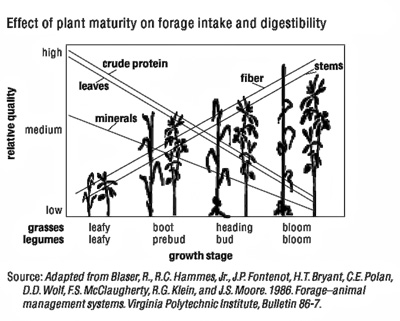

The primary influence on quality is the stage of plant maturity at harvest. As plants mature, nutritional content decreases, because the amount of stem increases and seed heads eventually form. Besides being lower in nutrition, stiff stems are prickly in animals’ mouths, so animals do not like them.

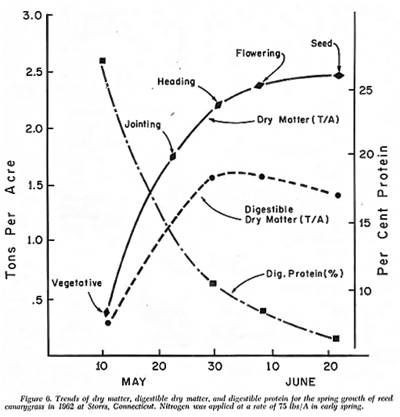

There’s definitely a sweet spot for harvest. If you harvest too early, you run your equipment while getting little hay; harvest too late, and most of the hay lacks quality. The two figures below show these effects.

The first shows that as the plant matures, crude protein levels decline as fiber increases. The plant is growing tougher stems so that it can stand up.

The second figure shows that as the plant grows, it produces more tons of total dry matter per acre, but quality, measured as digestible protein, decreases. Digestible dry matter peaks but declines much more slowly than protein levels. On May 30, in this case, total dry matter yield was good, digestible dry matter was maximum, and digestible protein was sufficient.

Timing harvest to avoid the decrease in quality relative to maturity is more important with first-cut hay than with second- or third-cut hay. At the second and third cuts, plants aren’t maturing as quickly because daylight is declining, so it’s easier to get quality hay.

The species of hay plants also affects quality. Grasses are generally lower in protein at harvest than are legumes. Legumes are higher in calcium.

Cutting Hay and Managing Harvest

|

Start by doing a good job making hay. Cut early, in wide swaths. Cutting height depends on the species – e.g., orchard grass is cut low and Timothy, higher. Dry hay rapidly so that plants stop respiring. (Respiration uses up energy in their cells.) Don’t bale hay that is too wet, since it can then heat (an indication of biological activity… decreasing quality and potentially creating a dangerous situation – spontaneous combustion – if the hay is in the barn). Once baled, keep hay dry. A well-ventilated barn is ideal for storage.

Next, sample your hay and send it to be tested. Most farmers in the Northeast use Dairy One in Ithaca, N.Y. (FMI and prepaid mailers: 1-800-496-3344, [email protected], www.dairyone.com) Sample hay from each field or each cutting separately. One good tool for sampling, the Penn State Forage Sampler, may be available for borrowing from your local UMaine Cooperative Extension office. This big metal tube has a sharp end that can cut into the hay bale. Sample 12 to 20 bales, boring into the small end. Mix the samples and send off the mix.

Basic NIR (Near Infrared Reflectance) testing is a good choice for most farmers, for $18. Add wet chemistry analysis for mineral analysis for an additional $10 if you want to see if your animals need any special mineral supplementation.

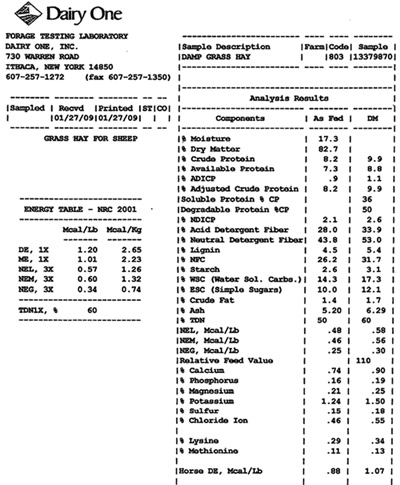

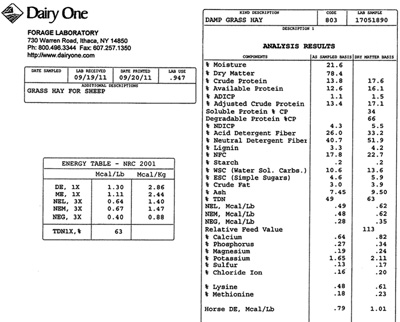

When your analysis comes in the mail, you may be overwhelmed by all the numbers. Dairy One has a nice fact sheet at www.dairyone.com/Forage/FactSheet/ForageAnalysis.htm that explains all the terms. Sample analyses appear with this article. Here are some basics.

First look at the DM (Dry Matter) column. These values of nutritional contents, measured after all the water has been removed from the hay, establish a base level for looking at different analyses. Values based on dry weight enable you to compare different types of feed, hay, grain and silage that originally had different moisture contents. You can see how well the feed will fulfill dietary requirements, which are also given on a dry matter basis.

Crude protein, a common measure of protein, is often used to compare forages or determine which grain to purchase. Protein levels are important to livestock; they are the building blocks of meat and milk!

|

Carbohydrates give the animal’s body energy to move and metabolize. Plant cell walls are made of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. Ruminant animals can partially digest cellulose and hemicellulose better than horses can, and non-ruminants digest these compounds only negligibly. This is why cows can live on forages but chickens can’t. All animals can digest the contents of the cell, where the sugars and starches are stored. As plants age, the relative amount of cell wall to internal cell contents increases, and the plant becomes harder to digest. This is why you want to harvest younger plants.

ADF, acid detergent fiber, is cellulose and lignin. These compounds are negatively correlated with digestibility.

NDF, neutral detergent fiber, is ADF plus hemicellulose. A 40 to 50 percent level is acceptable.

TDN, total digestible nutrients, is a common older measurement of energy, from times when more sophisticated tests weren’t available. Still valuable and often used, it is the sum of digestible protein, digestible NSC (non-structural carbohydrates), digestible NDF and 2.25 x digestible fat.

NFC, non-fiber carbohydrate, is a measure of the cell contents; starch, sugar, pectin and fermentation acids.

RFV, relative feed value, is based on digestibility and is calculated based on ADF and intake potential NDF. Alfalfa hay with 41 percent ADF and 53 percent NDF on a dry matter basis averages 100 percent RFV. A value of 100 to 150 is good; 150 to 175 is excellent.

One simple rule of thumb is to strive for 20 CP, 30 ADF and 40 NDF.

After you get these values for your harvested hay, look at the requirements for the animals you are feeding. The stage of production of the animal will affect its nutrient requirements. For example, a ewe being kept over winter and in early pregnancy will have a lower nutrient requirement than she will late in pregnancy, so save your better hay for later in the season and your best for when she is lactating. If you know you can meet an animal’s nutrient requirements with your hay, you needn’t supplement with expensive grain! This is your chance to save money.

Also, if you purchase hay, don’t pay extra for the best hay if your animals don’t require all those nutrients. Save money by buying poorer hay, and your animals won’t become fat and less healthy.

Resources

How Do I Select Quality Hay? North Carolina State University.

https://onslow.ces.ncsu.edu/files/library/67/-Selecting-and-Testing-Forages-On-Line.pdf

Putting Forage Quality in Perspective. Penn State University.

www.forages.psu.edu/topics/forage_qa/perspective/what.html

How to Read a Forage Analysis Report. North Carolina State University.

https://harrison.agrilife.org/files/2011/06/foragetool_2.pdf

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension organized five Hay School webinars last winter. They are available at these websites:

Hay School Session 1, March 1, 2012

https://connect.maine.edu/p7i3u0e7qta/

Hay School Session 2, March 8, 2012

https://connect.maine.edu/p1y6nzl1js7/

Hay School Session 3, March 15, 2012

https://connect.maine.edu/p93j3s92sog/

Hay School Session 4, March 22, 2012

https://connect.maine.edu/p166jw2atxp/

Hay School Session 5, April 5, 2012

https://connect.maine.edu/p1un21yrfc3/

I would like to thank Pam Child and her Coopworth sheep of Hatchtown Farm (www.hatchtown.com) in Bristol, Maine, for the idea for this article. If you have topics you think would be valuable for livestock folks to read about, please let me know.

Diane is MOFGA’s organic livestock specialist. You can reach her at [email protected] or 568-4142.