|

| Entrance to Duchy Home Farm, the organic farm of HRH Prince Charles. Robert Taylor photo. |

|

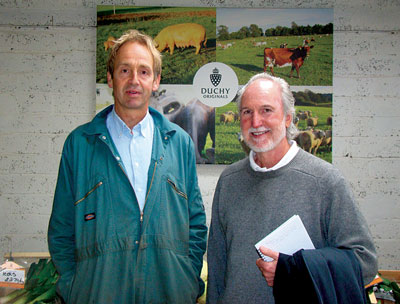

| Farm manager David Wilson and the author in the Veg Shed at the Duchy Home Farm. Robert Taylor photo. |

|

| David Wilson checks an apple tree planted between rows of vegetables. Prince Charles agreed to take responsibility for 1,000 of some 2,500 rare apple tree varieties in the Brogdale Collection. Robert Taylor photo. |

|

| Some 50-plus acres of vegetables grow on the farm. Robert Taylor photo. |

|

| Ayrshire cows enjoy a paddock of red clover. Robert Taylor photo. |

|

| The Highgrove Store in Tetbury. Robert Taylor photo. |

|

| The farm serves customers directly through its Veg Shed, open three days a week, and a vegetable box delivery scheme to about 200 families. Robert Taylor photos. |

|

By Robert Taylor

New Zealander Bob Taylor visited HRH Prince Charles’ organic farm, the Duchy Home Farm, and interviewed farm manager David Wilson in October 1994. That visit was reported in a feature article in The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, December 1995-February 1996 issue. In August 2009, Taylor revisited the farm to see what changes had been made over these 15 years.

For years HRH Prince Charles has been criticized and lampooned as anti-modern, an enemy of progress, old fashioned and naïve. The truth is, like many pioneers, he has been ahead of his time.

“He’s a man of huge vision,” says Patrick Holden, director of the U.K. Soil Association. “In the ‘70s he was talking about the environmental crisis, in the ‘80s he cottoned onto organic farming as a solution to build a more sustainable agriculture, and he was so far ahead of the curve that he was dismissed and in some cases is still dismissed today.” (“Prince Charles: Patron Saint of Organics,” Mark Phillips, CBS News, Oct. 5, 2007)

Through his writings and speeches and in lobbying with government agencies, the Prince has given leadership to worldwide efforts to show the futility and dangers of conventional farming. He recognizes the enormous influence wielded by transnational agrochemical companies. He understands the difference between linear and cyclical perceptions of nature. He condemns western development programs that rob underdeveloped nations of their wealth and leave them polluted and more impoverished. He champions the small family farm and sustainable agriculture.

In the 1980s, Prince Charles became convinced that organic was the way forward, and as landlord to some 135,000 acres of farmland (see sidebar on the Duchy of Cornwall), he had unique resources at his disposal to prove and promote his views. Through the Duchy, in 1980, he bought Highgrove estate, with 340 acres of farmland. In 1985 he bought adjacent Broadfield Farm with 420 acres, and he appointed David Wilson to manage the farm. Conversion to organic certification began in 1986, and more acreage was added over the years. Today the Duchy owns 1,120 acres and leases another 800, resulting in more than 1,900 acres, all under Soil Association certification.

Many of the Prince’s long-advocated concerns are only now being vindicated, and he has gained a good deal of deserved respect. Organic farming is booming, and the Duchy Home Farm is one of the U.K.’s largest organic farms. With more than 20 years of success, the farm has become well known around the world and is often visited and studied by scientists, researchers, journalists and other farmers. A three-year study conducted by the U.K.’s three Research Councils looked at the results of the organic regime on the farm, comparing, where necessary, with neighboring conventional farms. The findings produced solid evidence of the environmental benefits of organic farming, particularly regarding nutrient management and wildlife.

Visiting the Duchy Home Farm

Located about two hours west of London near the beautiful village of Tetbury in Gloucestershire, the farm adjoins Highgrove House, the Prince’s primary residence. Arriving for my meeting with Wilson, who has managed the farm since its inception 25 years ago, I found him in coveralls doing maintenance on a tractor. What I remembered most from my 1994 interview was his enthusiasm. Like the Prince, Wilson is passionate about organic farming, speaks earnestly of the need to work in harmony with nature, and has dedicated his life to winning the hearts and minds of others to the cause.

The Perennial Importance of Healthy Soil

Wilson says his conventional agricultural training made him skeptical of growing anything without using fertilizers and sprays, so his eyes were opened during his first years as he discovered the soil building quality of red clover and various grasses.

“The key to everything we do here is rotation. We have a seven-year rotation, three years of clover and grass, where we’re building nitrogen and increasing fertility, followed by four of arable crops. The first one will be wheat, followed by oats, then beans, and either rye or barley. Rotations were what enabled us to grow crops in the past, and I think will probably be the only way of growing crops in the future.”

Wilson singles out red clover as an amazing green manure. “When I first came here, I thought, my gosh, we normally would spend a lot of money on fertilizer to get a crop, and here we are getting this crop absolutely free, because it fixes atmospheric nitrogen in the soil.”

Spreading barnyard manures onto the paddocks also builds the soil. Over the years, Wilson says, he has learned to lightly compost barnyard manure before spreading it, which makes it much more effective.

The 15 miles of hedgerows around the paddocks have also been important. “The Prince is very keen about hedgerows,” says Wilson. “There’s a lot more to them than just the nice look. These hedges not only slow air flows, but also offer winter habitats for predatory insects, birds and small mammals, all important to the organic system.”

Preserving Rare Native Breeds and Plants

The Prince is patron of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust and has worked hard over the years to preserve native breeds in the U.K., many of which have been replaced by foreign breeds more conducive to intensive farming.

“The whole subject of gene preservation is very important,” Wilson asserts. “We are now dependent on fewer genes than ever for our food, which leaves us in a very vulnerable position, but nobody seems to realize it. The multinationals shape everything that we grow and everything that we breed, and it’s getting extremely narrow, worryingly narrow.” Animals such as Tamworth and Large Black pigs, Irish Moiled, Gloucester, Shetland and British White cattle, as well as Hebridean and Cotswold sheep, are utilized at the farm and valued for the quality of their produce and their natural affinity with the British farming landscape.

“For example,” Wilson say, “the smooth, pure white fat quality of our rare breed pigs cannot be obtained with modern hybrid pigs. Makers of preserved meats provide a ready market for this quality produce.”

Wilson believes that every farm should do its part by preserving a few rare varieties of plants or a couple of rare breeds of animals. Recently the Brogdale Collection could no longer afford to maintain its 2,500 or so rare apple varieties, so the Prince, because of his concern about the rapid loss of plant species, agreed to take responsibility for 1,000 of the varieties. Wilson now companion plants rows of apple trees between his veggies.

“These old breeds were developed for all kinds of purposes, such as to produce fruit which stores well, or trees which perform well in drought conditions. Over time we will graft together some of the most desirable of these characteristics.”

Commenting on his 180-head dairy herd, Wilson says, “The Prince told me he didn’t want another black and white breed, so we keep Ayrshire cows, which are a native breed, well suited to organic production, and very good producers from forage. At the end of the day, that is what we should be using our cows to do, to produce milk from grass either in its grazed form or preserved form as hay or silage. So our cows are producing a humble 5,000 liters [1,100 gallons], but they do it off a very, very low amount of concentrate feed.” Wilson explains that intensive herds can produce 8,000 or 10,000 liters, but with the direct cost of expensive grain feeds, the indirect environmental costs associated with those inputs, and the detrimental effect on the animals’ health, it is neither cheap nor sustainable.

Interaction Between Farm and Community

Wanting the farm to interact more with the local community, the Prince encouraged Wilson to develop direct ways to engage consumers. The farm now has about 50 acres in vegetables, supplies about 200 local families through a veggie box delivery scheme (a Community Supported Agriculture system, in U.S. terms), and three days a week sells directly to the community through its on-farm Veg Shed.

Because of the strict grading standards of supermarkets, much of what organic growers send to market is often rejected. “Over the years we’ve gotten infuriated with the supermarkets with this whole business of out-grades,” says Wilson. “In the U.K., in overall terms, we throw out over half of what is grown. I’ve yet to meet anybody who says, ‘Can’t eat that carrot, it’s curved,’ or, ‘This carrot has a bit of a ripple halfway down.’ It is quite ludicrous. We now bypass the supermarkets because we don’t want to get involved in this whole business of long distance transportation, centralized packing, sorting, grading and distribution. We now have more contracts supplying directly at reasonable prices. One contract we have is with South Gloucestershire County Council, where they buy our organic potatoes for use in school lunches.”

Sustainability: the Measure of All We Do

“Sustainability in its truest sense is how we have always looked at everything,” Wilson asserts. “It involves the efficiencies of the way we produce our food. How sustainable is everything we do?” He argues that one important outcome of applying more sustainability measures (carbon footprint, etc.) will be documenting the huge unsustainable damage caused in making and using artificial fertilizer, such as ammonium nitrate. Wilson contends that over half the energy used in the conventional farming system comes from the manufacture and transportation of ammonium nitrate; and applying it to the soil causes a massive release of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide. “As more people realize this fact,” Wilson points out, “the strength of the organic system, which builds its own soil fertility naturally, will be validated.”

Regarding methane release from ruminants, Wilson envisions fewer ruminants in the future but feeding them naturally. “Feeding grains to ruminants on a big scale is incredibly inefficient. A huge amount of energy is embodied in growing cereals, plus, because they have evolved to eat low grade plant material, the ruminants process it [grains] very inefficiently.”

The Future of the Duchy Home Farm

Prince Charles is devoted not only to the ideas of organics and sustainability, but he also is keen to walk the paddocks, visit the dairy shed and witness a harvest.

“Not more than three weeks go by without the Prince visiting the farm,” says Wilson. “Some weeks he’s here on three or four occasions. I send him regular reports and he’s always interested in what’s going on.”

When Prince William becomes the Duke of Cornwall and oversees the Duchy and the Home Farm, Wilson expects that he will follow his father’s passion. “Both Harry and William enjoy the countryside,” he says. “It’s where they were brought up, and they have a good understanding of it. Both are countrymen at heart.”

For more information

www.duchyofcornwall.org

www.princeofwales.gov.uk

The Duchy of Cornwall

In 1337, King Edward III set aside huge tracts of land into a trust to provide an ongoing income for the eldest surviving son of the Monarch. When the male heir becomes the Duke of Cornwall, the income and eventually the management of this huge landed estate (the Duchy) becomes his entitlement. Charles is the 24th Duke of Cornwall. Today the Duchy consists of about 135,000 acres in 23 counties located predominantly in the Southwest of England. All of the estate, including some residential and commercial properties, is tenanted out. The vast majority consists of about 300 small family farms. In 2008-09, the Prince’s income from the Duchy was £16.5 million. Well over half of his after tax income was spent on official duties and charitable activities. His Duchy Originals organic food company, started in 1990, now offers more than 250 products, has exceeded annual sales of £50 million, and has generated over the years more than £7 million in after tax profits, all of which go to the Prince’s charities.

Accounting for Sustainability

In 2006 the Prince convinced the leaders of some 200 U.K. businesses and government agencies to agree to develop and test measurement tools to assess the impact on the earth of their various products and services. Within a year there was broad participation from all around the globe. A reporting scheme called “Connected Reporting Framework” (CRF) has been developed and is now showing up in the financial reporting of major corporations. Herein are reported measures of greenhouse gas emissions, energy usage, water use, waste, and significant use of other finite resources. The overall goal is to develop measures of well-being and sustainability so that the performance of business and government enterprises can be evaluated in those terms rather than simply in terms of growth in consumption.

In a lecture at St. James Palace on July 7, 2009, the Prince said: “It seems to me a self-evident truth that we cannot have any form of capitalism without capital. But we must remember that the ultimate source of all economic capital is Nature’s capital. The true wealth of all nations comes from clean rivers, healthy soil and, most important of all, a rich biodiversity of life. Our ability to adapt to the effects of climate changes, and then perhaps to reduce those effects, depends upon adapting our pursuit of ‘unlimited economic growth’ to that of ‘sustainable economic growth.’”

Robert Taylor is a freelance writer. His articles on environmental and health issues have appeared in Organic New Zealand Magazine, New Zealand Farmer, and The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener. His travel stories have appeared in the New Zealand Herald and the Herald on Sunday.