|

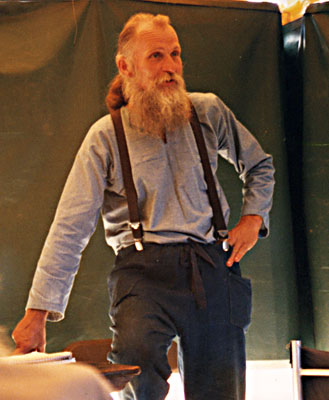

| Will Bonsall spoke about intercropping and succession planting at the Common Ground Country Fair. English photo. |

By Jean English

Will Bonsall’s original inspiration for growing crops intensively on his farm came from the book Farmers of Forty Centuries, by F.H. King. Paraphrasing a point from the book, Will told an audience at the Common Ground Country Fair, “Such crowding of plants on the land must be accompanied by crowding of gray matter in the brain.”

Another source that he found useful in developing his farm plan was John Jeavons. Following Jeavons’ advice, “We’ve experimented with raised intensive beds. We liked the intensive but not the raised. Some people swear by [raised beds]; we swear at them!” He and Molly Thorkildsen found that raised beds were too dry (Will and Molly don’t irrigate), so germination was poor. Rains washed seeds off of the beds and into the paths. Raised beds were a lot of work, too. “We still do beds, we just flattened the beds.”

The beds at their farm, Khadigar, are 6 feet on center, 4-1/2 feet wide, with 1-1/2-foot-wide paths. “My wife and our apprentice don’t like the width” and would like narrower beds, but the lanky Bonsall says that he wanted 75% cropland, not 67 percent.

Interplanting plays an important role in achieving high yields at Khadigar. Squash, for instance, doesn’t go into the ground until around Memorial Day, and it doesn’t spread much for a good four weeks after that. So in early spring, they set cabbage plants in rows 12 feet apart, with oats, barley and peas in between. The resulting biomass can be turned under, or mowed and then mulched with shredded leaves, when the squash is planted midway between the rows of cabbage around the first of June. (Actually, some biomass can keep growing in the paths between the cabbage and squash until the squash starts to spread.) By August 1, the cabbages have been harvested and the squash fills the plot.

Bonsall pointed out that peas and carrots, and soybeans and corn, are often recommended as good “companion plants,” and that some gardeners believe that the legumes benefit the nonlegumes by providing nitrogen. “But the nitrogen is not available to plants until the next crop” is grown, Bonsall explained. “The legumes don’t help the [companion] crop, they just don’t hurt them. The legumes get their own nitrogen, so they’re not robbing soil nitrogen from the carrots or the corn.” Still, however, the yield on such interplanted plots is greater than the yield if both crops were grown alone.

For example, when planting vegetable soybeans and sweet corn, Bonsall said to plant the sweet corn at 100% spacing: rows 3 feet apart, with 6 to 8 inches between the kernels. Then drop a soybean in about every foot. This is a “much reduced spacing” for soybeans-maybe 25% of their normal plant density. So, theoretically, the best yield you would get would be 125% production. “You may not get that much, but the soybeans are gravy. You get a huge windfall of soybeans with 100% corn.”

To increase the yield of fava beans, Bonsall said that after harvest they die back, but a large percentage of the plants (sometimes all of them) send up suckers, which give a small, late crop of fava beans. When some members of the audience asked how to grow soybeans that taste good, Bonsall said, “People either like or don’t like the taste. The Windsor types have a tough skin. The larger seeded ones are more tender.”

Carrots and Rocambole garlic are planted together at Khadigar. On a 474-foot-wide bed, he plants two rows of carrots, a row of peas down the middle of the bed, and two more rows of carrots on the other side of the bed. The peas (or pole beans) are held up with alder branches.

Pole beans are grown on an A-shaped trellis, with lettuce, parsley, radishes, etc., going in the center of the trellis before the beans are planted. Melons can be grown on a trellis, also. “Think of the garden as three dimensional,” said Bonsall. “Grow up.”

To interplant field corn and pumpkins, Bonsall recommended planting three rows of field corn, one row every 3 feet, then skipping the fourth row; that’s where squash or pumpkins are sown. “So the pumpkins are planted every 12 feet,” he explained. This is a 100% planting density for pumpkins and 75% for corn. “You could expect a 175% yield,” Bonsall said “Actually you get about 80% on the corn, because more light hits it where the corn row was left out.” On the other hand, you get 50 to 60% productivity from the pumpkins due to shading by the corn. Still, the total productivity is greater than 100 percent.

Three rows of cabbage can be planted in a 4-1/2-foot-wide bed, with lettuce sown between the rows. The lettuce is harvested before the cabbage grows too big. Likewise, lettuce can be planted before and between tomato plants.

Onions are grown in rows that are 8 inches apart, with nothing in between. “Onions do best by themselves.” They are mulched with shredded leaves.

In early May, sunflowers are seeded 1 foot to 1-1/2 feet apart in a row down the middle of beds that are 6 feet on center – a 50% density planting. Three weeks later, white runner beans are grown on the sunflower stalks, with four seeds being sown at the base of each sunflower – close to 100% density. A single row of soybeans is planted on either side of the row of sunflowers and runner beans to complete the bed sowing.

Wheat and field peas can be grown together. The wheat is sown at 100% density, the field peas at about 10 percent. The peas get physical support from the wheat, while the wheat gets some weed control from the broad leaves of the peas. “The trick is,” said Bonsall, “you need a field pea that matures at the same time as the wheat and is compatible in height. And what is the correct density? I’m still not sure.” To harvest wheat and peas, Bonsall said that you could combine or sickle them all together, bind them together, put them in shocks together, thresh and winnow them together, then screen them to separate the two crops. “In India, they grind and mill it all together to make chapatis.” Bonsall has tried planting this combination and has found that it looks promising, but hasn’t come up with the right varieties or spacing yet.

Some members of the audience said that the traditional “Three Sisters” planting of corn, beans and squash hadn’t worked for them, and even the corn-bean combination hadn’t worked. “The beans pulled the corn over.” Bonsall said that a shorter variety of bean may have worked, and added that the Three Sisters planting idea is a good illustration of the complexity of intercropping. Native Americans must have had it worked out, with specific varieties and planting times, to make the system work, he explained. It won’t work with just any variety or planting time.