By Caleb Goossen, Ph.D., MOFGA Crop Specialist

With gardens put to bed for the winter, now is the time when gardeners reflect on the prior season and begin planning for the next. For many, it is the time to evaluate seed supply, and order seeds for the coming year. This is also a great time for new gardeners to start planning their first garden.

How to Choose Varieties

Variety selection is inherently very personal. I encourage you to first think about your gardening needs and desires: What do you enjoy eating? How much space do you have in your garden? As with most gardening decisions, selecting varieties is always easier if you have past experience to draw upon. This is one reason why I encourage people to set aside garden space for experimenting with new things, like new varieties, as well as to keep some records — whether that’s writing highly detailed notes in a calendar or simply taking photos throughout the season. Looking back through them can refresh your memory of how you felt a crop was doing in the moment.

If you don’t have prior experience, or are looking to try out some new varieties, a great first step is to ask other gardeners their favorites: What has worked well for them? What do they find easy to grow? Or what is difficult to grow but worth it for the flavor?

An independent recommendation you can look for in seed catalogs is the All-America Selections (AAS) logo, indicating a winning variety from their nonprofit trialing. Every seed company differs in what information they share, but most will provide a description, “days to maturity” (though take caution that different suppliers may use different definitions, some start that count at seeding date while others start it at transplanting date), information about disease resistance (if present), whether a variety is open pollinated or a hybrid (often denoted “F1”), and if a variety is subject to intellectual property restrictions. If you intend to save your own seed in the future, it’s best to stick with open-pollinated varieties, and to avoid F1 hybrids which may yield a highly unpredictable second generation from saved seed. Sometimes suppliers like Fedco Seeds will provide even more information, like if a given variety supports the efforts of independent breeders, small independent growers or cooperative seed growers, or pays royalties to specific seed keeping communities.

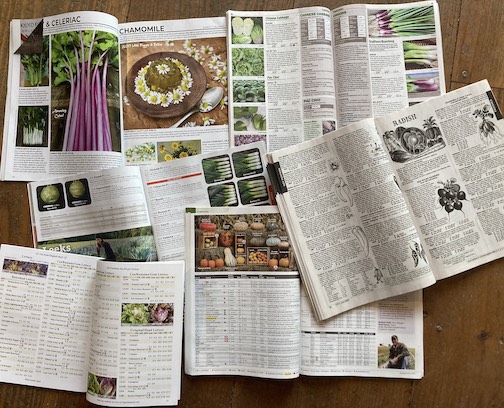

I find the allure and promise of seed catalogs’ beautiful photos and descriptions, bringing my winter imagination into the summer months, to be one of the great joys of growing, and I encourage every gardener to let their imagination wander a bit (within budget) and devote a little space to trialing a new variety or two, as that can greatly inform your future plans!

How Many Seeds Do You Need?

Similar to selecting varieties, buying the right quantity of seeds is easier with more gardening experience, and even more so if you keep records. What did you grow last year? Was it enough? Did you run out of a fresh or storage crop earlier than you would have liked? If you use social media, pictures that you posted previously can help jog your memory if, like me, you struggle to keep garden records.

Without prior records, a good first step in determining your seed needs is to estimate your normal usage of a crop. If your household uses about seven onions per week you would probably want to aim for somewhere in the neighborhood of 400 onion plants. Heading crops like cabbage or lettuce, and root crops like carrots, parsnips and rutabagas are particularly easy to estimate seed needs this way, as one seed produces one plant that is equivalent to one individual vegetable — though it’s always safest to assume that some plants won’t make it, or may be smaller than desired at harvest. Fruiting crops like tomatoes, squash, etc. are a little trickier to estimate. Some seed companies provide yield estimates, and Johnny’s Selected Seeds has some nice tables describing average yields per 100 feet of row, as well as examples of succession planting schedules. Succession planting is probably an under-utilized method in most gardens, but its benefits do come with an increase in the amount of seed used for a crop over the course of a year.

Different seed starting styles can dramatically change the amount of seeds used for a given crop. If you start seedlings in trays, and then prick them out individually into seedling cells/pots, you can get away with very little seed, versus sowing multiple seeds in each cell/pot that you later thin out. Both of those methods may use much less seed than sowing directly into soil outdoors, however.

Are Old Seeds Ok to Use?

Like most things biological, the answer is “it depends.” Seed viability varies by species, seed size and, to a great extent, its storage conditions, but most garden seed is estimated to remain viable for two to ten years. Smaller seeds often have a shorter “shelf-life” than larger seeds, but all seeds exhibit the greatest viability and vigor if stored dry and cool — I keep all of my seed in a chest freezer.

Seed vigor (how well it starts growing) is almost as important as viability (can it start growing). To give your garden its best shot, it is important to use healthy and vigorously growing seedlings. Seedling vigor is the product of many factors, but one of the most important is how quickly it germinates and makes leaves to fuel further growth. Extended germination time in the soil provides more opportunities for damping-off diseases to damage or kill a seedling before it has started to make its own food, which it will use to better defend itself.

Older seeds’ vitality can be easily checked with a quick germination test. There are many examples online, but the basic idea is to wrap at least 10 seeds in a moist paper towel, and place them inside a slightly open plastic bag to protect them from drying out. After a week or so in a warm location the percentage of seeds that fully germinated is that batch of seeds’ germination rate. A lower germination rate can be compensated for by seeding more densely and pricking out vigorous seedlings for transplant to individual containers/cells or simply thinning out less vigorous seedlings at an appropriate spacing if already planted where desired.

When to Buy Seeds vs. Seedlings

Starting your own seeds may feel like one of the key elements of being a gardener — I always enjoy it as a way to start my spring regardless of the outdoor conditions — but it doesn’t always make sense for folks to start all of their own seedlings. If you’re already well set up to grow your own seedlings it is typically less expensive, but professionally grown seedling starts are more expensive than seeds precisely because they represent a lot of value from the time, experience and everything else that has been invested in them. Greenhouse production can often result in strong vigorous starts that are already better acclimated (“hardened off”) to the bright light and windy outdoor conditions that will be present in a spring garden. However, seedlings of certain crops might be just as easy for gardeners to start indoors, or to seed directly in the ground, with similar or better results as those purchased from a greenhouse — and with a lower cost. Crops that I recommend against buying as finished seedlings, and instead growing from seed, include short-season crops that grow quickly like small greens (lettuce mix, Asian greens), quick root crops (spring turnips, radishes), beans and peas, some annual herbs (dill, cilantro), and crops that can be more difficult to transplant such as tap-rooted root crops (carrots, parsnips). Cucurbit crops (squash, cucumbers, melons) are more nuanced, as they are quick growing and often considered difficult to transplant — but I start all of my cucurbits as seedling transplants and wouldn’t hesitate to purchase cucurbit starts if they’re well grown. Their reputation for poor transplanting likely stems from folks attempting to plant out seedlings that are overgrown — most transplants do best when they’re planted out before their root systems get too big for their containers (which happens quickly with cucurbits, and they are more sensitive to root disturbance). I recommend seedlings (purchased or grown yourself) for long-season, easily transplanted crops that do best with a head start, like nightshades (tomatoes, peppers, eggplant), alliums (onions, leeks) and brassicas (broccoli, kale, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, etc). A very common problem encountered when starting seedlings at home is not providing enough heat and light, especially for heat-loving plants like nightshades. For this reason, even some farmers choose to buy in their nightshade seedlings. Every spring, MOFGA updates a map of locations where one can buy certified organic seedlings (mofga.org/mofga-seedling-map/), and at the very least it’s nice to know where to go as an “insurance policy” if your own starts do poorly!

This article was originally published in the winter 2022-23 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.