Keep it easy, motivating and enjoyable

By Jennifer Wilhelm

As a small-scale fruit and vegetable farmer, I spend hours each year planning for the growing season. When the ground is still frozen and daylight is at a minimum, when the seed catalogs flood my mailbox — harbingers of the color, smells and tastes to come — I sit down with my laptop and get organized. I plan what to grow, how much to grow, and where on the farm to grow it. I create spreadsheets with seeding and transplanting dates, and make notes about how a crop performed on our farm in the past and what it needs to be successful again. I feel prepared.

When seed ordering is done and the catalogs are neatly stacked on the coffee table, I wait for the seeds to arrive. And when they do, I excitedly track what has been seeded and when, germination dates and rates, and the dates trays are moved from the grow room to the greenhouse. At the time seedlings are ready to be transplanted, I diligently track my progress, filling the spreadsheets with more data. Then, the harvest begins and I shift from typing data into spreadsheets to writing details in a paper calendar. At the farmers’ market I note items sold on a dry erase board (half of which is wiped off before I get back to the farm). A pest arrives and I scribble notes on random pieces of paper in one of the greenhouses or in the barn. By mid-July, when I can barely keep up with the harvest, watering and marketing, all my careful record-keeping plans fall apart.

It’s a familiar story. Farmer plans. Farmer’s plans are upended. But what if I told you there is a way to maintain organized records, even if, like mine, your record-keeping plans typically go sideways mid-season? Enter Taylor Mendell from Footprint Farm, who said, “If we don’t need a record, we don’t keep it. If we do have to keep records, we do it in the easiest way possible.”

This past January, MOFGA offered an in-depth record-keeping webinar with Mendell, and given my track record, I signed up for it as soon as it was posted.

Mendell runs Footprint Farm with her husband, Jake, and is the architect behind their uber-efficient record-keeping processes. In addition to managing the farm’s 120-150 family Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), she also founded and runs Habit Farming, a network focused on building community among farmers and sharing resources for how to increase efficiency (and financial stability!) with a variety of record-keeping tools.

She has honed her record-keeping skills over the last 10 years, seeing her farm through its own evolution from its beginning in 2013. Her farm is located in Starksboro, Vermont — zone 4 on the hardiness map — which means the growing season is short. But despite the northern New England climate, they manage year-round vegetable production on 1.5 acres outdoors and a quarter acre in unheated tunnels, with 1 acre in cover crop each year. The farm employs four full-time employees (plus two owners) May through October, and two part-time employees (plus two owners) November through April.

Mendell started off the webinar with an important question, “How do you determine which records to keep?” The answer is different for every farmer. For Mendell, adhering to a simple record-keeping philosophy of “keep it easy, motivating and enjoyable” helps her decide which records to keep. She and her farm team focus on tracking only the data they need, or have decided they want.

Of the many helpful tips Mendell shared, she suggests taking time to suss out how to categorize your data at the outset. Level one data includes all information that is mandatory, or a matter of law, such as information for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) or the Department of Labor. Level two data are obligatory but are more a matter of social or moral obligation to track rather than the rule of law, such as data required for organic certification or a granting agency. The last level of record-keeping captures the remaining data: all of the information that you’d like to track, but that is completely voluntary such as weather reports, pest issues or cover crop germination rates.

With an understanding of the different types of data and how they must be handled, Mendell shared a number of incredible tips and tricks for staying on track with record-keeping throughout the year.

She suggests “working clean” when setting up an office space. Everything you need to access regularly should be within reach and set up for the brain that is using it the most, she said. This includes everything from when and how to collect the data to how files are stored to how long the data need to be kept on file. Mendell’s office, while not always spic and span (it is the office of a working farm after all), has a natural flow.

Paperwork moves from left to right, and every type of paperwork has a proper filing structure. She can pick up a piece of paper in her inbox, turn to her computer and input data, then file the sheet in the appropriate storage unit, all while sitting in the same seat. To know where to find or file an invoice, Mendell uses file naming conventions that make sense to her as she’s the primary office manager.

“My husband thinks of everything in numbers and is able to remember when he went to Tractor Supply and bought that stuff in May, so he would want to have his receipts set up by month. I don’t think that way. I think I went to Tractor Supply, so I’m going to file it under ‘T,’” she said.

To reduce redundancy and increase efficiency, Mendell takes the time to identify places where she can “do the thinking once.”

“I fill out this form to send with our IRA contributions for our employees every other week,” she said. “All last year I was filling it out by hand every other week, and it was so annoying. Today I took five minutes and I filled it out on the computer, then I made copies of it for the year, so I never have to look up where to find that specific piece of paper. It’s just going to be sitting there waiting for me once the season starts.”

Her organizational systems aren’t bound to the office, they can be found in all aspects of the farm operation. I was reassured to hear that the team at Footprint Farm also switches from developing spreadsheets digitally during the off season to tracking data by pen and paper during the farm season. The difference at Footprint Farm is that they are very intentional about their pens and paper, which are kept in appropriate logbooks in convenient and accessible locations (in other words, not on random pieces of paper scattered around the farm).

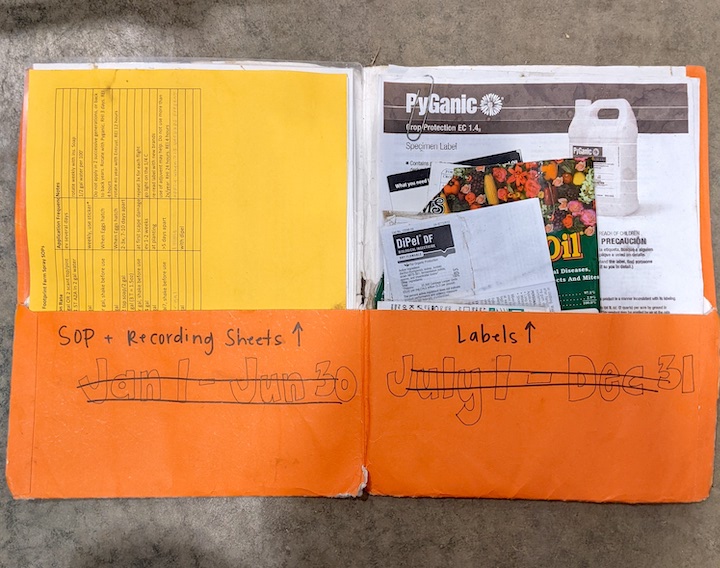

Finding the right tools for the job is part of “making it easy for people to be successful,” said Mendell. The Footprint Farm team simplifies complex spreadsheets before printing, and uses “write in the rain” paper, which doesn’t smudge or get eaten by rodents, when collecting data in the field or wash station. Important standard operating procedures (SOPs) are laminated and kept in the associated logbook. For example, their spray log includes a list of all of the organic fertilizers and pesticides they use, the application rates, and scope of use for each product. That logbook also includes the labels from each product in the event that a new pest or problem pops up that they haven’t encountered before; they don’t have to go look it up, they can just reference the label.

Mendell and her staff track their pack-out quantities on a dry erase board and take photos of the board each day for their permanent records (duly noted). They also use reusable plastic totes for packing produce that get labeled with liquid chalk markers that can be erased. And importantly, everyone knows whose responsibility it is to log each type of data they are tracking.

All of these examples demonstrate Mendell’s record-keeping philosophy of keeping it easy, motivating and enjoyable at work. She also stressed the importance of “doing the thinking once,” setting up systems where decisions have already been made and just require execution, by developing SOPs, ensuring everyone knows where to find them and how to use them, and procuring the tools that fit the job.

Let’s say that you adopt and implement some of these record-keeping strategies. How will you know if you’re successful? Part of organized record-keeping pertains to understanding your bottom line and budgeting in a way that allows you to not only pay the bills but to also set money aside for savings and retirement. Mendell and her husband made a very calculated decision at the outset that they didn’t need to have a deep understanding of their “cost of production,” which requires a well of data and commitment. “How much does it actually cost to produce a bunch of carrots on my farm?” said Mendell. “I don’t know what it costs to produce any single crop on my farm, and that’s because it was a choice that we made early on that instead, we really wanted to focus on the question, ‘Is it enough?’”

If knowing how much it costs to grow a bunch of carrots (or a pound of onions, or a bushel of apples) is not a priority for you, then you don’t need to collect all of the data needed to answer that question. Mendell uses a Holistic Management Institute (HMI) form of bookkeeping and budgeting, which spins the process around. Instead of focusing first on how much money can be made given the land area and resources, HMI allows the focus to be on setting financial goals that may at first glance seem unrealistic.

“So instead of saying, I’m farming on this much land, and I’m growing these things, and this is how much money I can probably make, and then trying to squeeze expenses to fit, we’re going the other way around,” explained Mendell. “I didn’t think that an acre and a half could make $300,000 when I set our budget last year, but it was a very motivating way to do budgeting because it pushed us to find other sources of income.”

To meet that goal (and they did), Footprint Farm included “add-ons” in their CSA from other businesses, and pushed their own production beyond what they thought they could. Now, with a better sense of financial security and 10 years of farming experience at Footprint Farm, the Mendells are ready to dig deeper into cost of production analyses. Instead of focusing on if they’re making enough money, they can ask: “What should we be charging for these things?”

“I feel motivated to do a cost of production study in a different way,” said Mendell. “Because we’ve had really bad germination in our high tunnels for our first round of carrots, I’m curious about comparing direct-seeded versus paper-potted carrots.”

Looking at cost of production in this way, Footprint Farm will not only be able to understand how much it costs to produce carrots on the farm but also which production methods are most efficient. And they are now in a position to spend the organizational time on this type of record-keeping, which may not have been possible when they were first starting out.

Incorporating the theories behind “working clean” into their record-keeping strategy has put Footprint Farm in a position to be successful long term. Though careful planning might not translate into successful record-keeping, implementing systems strategically across the operation can.

This article was published in the summer 2023 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, MOFGA’s quarterly publication.