|

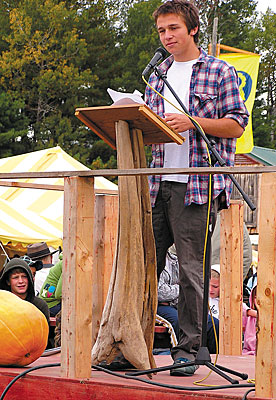

| High school student Sam Levin, who started a student-run garden at his school, told Common Ground Fairgoers, “We can change the world. It’s just going to have to happen one plate of bomb tomatillo salsa at a time.” English photo. |

By Sam Levin

A junior at Monument High School in Great Barrington, Mass., Sam Levin is one of three co-founders of Project Sprout, an organic, student-run, 12,000-square-foot garden on the grounds of his school. Project Sprout supplies the school cafeteria with fresh fruits and vegetables, helps feed the hungry in the community and serves as a living laboratory for students of the Monument school system. Levin’s story is a remarkable portrait of vision and persistence. Inspired by Alice Waters’ The Edible Schoolyard, Levin and his peers are transforming their community’s relationship to the land and their food. Levin was the keynote speaker on Friday, Sept. 25, at MOFGA’s Common Ground Country Fair.

This story begins with a basket of string beans. One afternoon in July, someone had harvested too many string beans from the garden, and we had a basket full of them with nowhere to go. I happened to be heading into town with some friends, so I decided to take the beans to Main Street. My friends and I went into each business with the basket, offering people to try the fresh produce. And the reactions were pretty hilarious.

The first store we went into was a fancy clothing store, and we held out our beans and offered them to try some. They looked at each other nervously, and then at us, and asked, “How much are they?”

We said, “Well, they’re free, we just want you to get to try them.”

They were shocked. Next we went into a coffee shop, and the girl working there was so excited that she announced it to everyone in the cafe.

In the hardware store, the two old men didn’t really say much, and didn’t seem that excited, but by the time we got to the door on our way out almost all of the beans we had given them were gone.

Right as the basket was being finished off by the last few businesses, my friends and I had to leave. On my way out of town, I imagined myself as a tourist walking down the street, looking in the shop windows, seeing every single store clerk munching on string beans and being totally confused.

Seeds of an Idea

Before I go on, I want everyone to imagine the last time you shared food with someone – whether it was cooking a meal for friends, selling your produce at a farmers’ market, or handing a complete stranger some free beans. Because my story that begins with a basket of string beans is really about sharing food, and it will help if everyone can remember the experience of doing just that.

OK, good. Now I need to backtrack a little bit. I said that the beans came from the garden, but I skipped over the explanation of what garden, and that’s because that’s a whole story in and of itself.

Growing up I would go out to Long Island every summer to where my grandparents live, and work on my grandfather’s farm with my brothers. In addition, down the road from my house in Western Mass. is a small farm with a few cows, a pig and some chickens. I spent a good portion of my childhood hanging out on that farm – jumping between hay bales, playing soccer with piglets, and riding cows. And when I wasn’t there, I was in the woods and swamps exploring the natural world.

In middle school, I began reading books by a biologist named E.O. Wilson, and I declared myself a biologist. [When I was] in eighth grade, he published a book called The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth. At around the same time, Al Gore came out with “An Inconvenient Truth.” I was struck by the urgency with which I needed to act to save what I had grown to love the most – the natural world.

In September of my freshman year, while thinking about what I could do to help the environment, I read an article in Sierra Magazine about the top 10 greenest colleges in the country. Most of them were getting their food locally, and a few had small gardens too. That same month, I picked up a book off my shelf that my oldest brother had given me. It was An Omnivore’s Dilemma. Suddenly the connection was merged between my love of biology, my urge to save life on earth, and my childhood on farms.

I began to think that our school should source its food locally. I met up with two other students, who had been thinking along the same lines, and we began talking about it. At first, we though that having a little garden would be a good idea too, for kids to get to see the connection between the cafeteria and what happens on the farms. But we realized that there was a lot of empty space around our school. We started thinking, well, if we could make a really, really big garden, sort of like a small farm, we could actually grow the food for the cafeteria ourselves, educating kids about food, farming and the natural world along the way. Thus, the idea of Project Sprout was born.

Luckily, we were naïve enough to not worry about all of the obstacles we would face. We simply decided we would make it happen, and went from there.

Early on, we started working with our guidance counselor to talk about our ideas. Soon after that, we connected to Project Native, a local environmental nonprofit that agreed to be our umbrella organization. We realized that the first thing to do would be to get approved by the school committee. So we spent months developing a concrete plan to present, and researching as much as possible.

A school committee meeting is something you usually spend five minutes preparing for in the car ride on the way to the meeting. But we knew that as high schoolers, we would be considered lazy, irresponsible, not able to follow through, and likely to just spend all of our time playing video games. So we knew we would have to prove that wrong by thinking everything through, and having answers to any questions they would ask.

We did, and we were approved. After that, we began working with Bridghe McCracken, a local professional gardener, to design year plans for the garden. We began fundraising, and planned a Local Food Pig Roast at a local restaurant to raise money for the garden. The Pig Roast almost fell through at the last minute, because we lost our pigs – which is tricky when your whole event is a Pig Roast.

We used the wrong machine to till the earth, and ended up having to do most of it by hand.

But by June of last year, we had a 3,500-square-foot garden between the three schools. We donated over 1000 pounds of produce to WIC, which stands for Women, Infants and Children.

Over the summer a kindergarten class came to the garden once a week, and we introduced them to things like sweet peas, and carrots that live underground instead of in a plastic bag.

At the end of the summer, I traveled to San Francisco, where I spoke at the eat-in to several hundred youth activists from around the country. That weekend, I was constantly looking around in awe, because it was the first time I realized how many people want to make the same thing happen – how many people, like all of you, want to make food, good food, real food, healthy food, a right of everyone, not just a privilege of a select few.

Faith in a Generation

We came back to school, sort of surprised that we had actually pulled it off, you know, actually grew a garden, and decided we might as well try having some lunches in the cafeteria. The director of food services agreed to check it out. At our cafeteria, on an average day, they sell between four and six salads. That day, with our produce, produce that kids had grown, we sold over seventy.

I still remember that first day, walking around the lunchroom, seeing kids’ faces light up as they ate fresh cherry tomatoes, cucumbers and lettuce. I actually have this picture of my friend cracking up as he stuffs his face with greens. It was a pretty awesome day.

Then I was invited to Turin, Italy, where I spoke to a group of 8,000 delegates gathered from 153 countries to discuss the food crisis. There, I made a promise that my group and I were not unique – that other kids could create similar projects in their own schools. I promised that we would be the generation to reunite mankind with the earth.

So, over the winter, as we made the plans for our expansion, and continued fundraising, we also started traveling to other schools, to make good on my promise that indeed, other kids could and would make this happen too.

I feel like a pretty confident person, and from what I see in my friends and siblings, I am even more confident in my generation than I am in myself. But I’m not gonna lie. I wasn’t so sure that my promise wouldn’t fall flat. At the first presentation, as my peers and I stood in front of 500 kids from across my state, for the first time since I gave a public speech, my knees shook.

We have been giving presentations – from New York to Martha’s Vineyard – and so far at every school that we’ve presented at, they have started a student-run garden.

And that’s a key word – student-run. The concept of a school garden is not a new one. But the concept of a completely student-run school garden is very different. High schoolers don’t listen to being told what to do. I am sure the high school teachers in the audience can attest to that. And I’m sure the other high schoolers out there can agree with me that we don’t take orders very well. You could walk into one of my high school classrooms and tell us that we had to eat the chocolate you had brought us, and just because you told us to, we wouldn’t do it.

It’s the same with a garden. But if you have your friends asking for your support in something they are working on, we will be there in an instant.

Plus, the little kids at the elementary school look up to the high schoolers, and when they see us in the garden, it makes the garden pretty much the coolest thing around.

Our school is not drastically different from any other public high school. But we’ve created a unique environment by having students driving the force behind this effort, and having teachers who support us in any way possible without trying to run the show or be overly involved.

Growing Pains and Pleasures

Now, in our second year, we have a 12,000-square-foot vegetable plot. Next to that are 100 raspberry plants, and on the other side is an heirloom fruit orchard that we planted in the spring. We had 60 high schoolers signed up to be a part of Project Sprout, about 40 of which come to the garden every once in a while, 20 who come about three times a week, and about 10 who are working on Project Sprout almost every day, either in the garden, fundraising, planning events and working with the cafeteria, etc. By the end of last school year, there was a class in the garden from one of the three schools in our district almost every day, usually taught by a high schooler.

We planned a second Local Food Pig Roast Fundraiser. Local farms donated produce, and we purchased three local pigs and got one donated. A farm-to-table restaurant hosted it again, and this time, we didn’t almost lose the pig. That day, about 30 high schoolers showed up in their Project Sprout T-shirts and lined up behind three tables to serve local food. Somehow, the rain held off, and we had 500 people gathered together, eating good food, listening to an awesome student band, and supporting Project Sprout.

Over the summer we worked four days a week, plus one day with a special needs program and one day with a preschool program. Our food service director was originally interested yet somewhat timid – which is expected and reasonable, considering we’re asking them to switch from frozen food in rectangular packaging to fresh produce still covered in dirt, crooked carrots, and some slugs mixed in with the greens. But now, she has stepped up to the plate in a huge way and agreed to use all of our produce. We deliver to her twice a week before school, and what she doesn’t use that day goes into the walk-in cooler for the next day. Not only that, but she has started to look up recipes for things like kohlrabi and soybeans. Who ever heard of a public school cafeteria serving organic kohlrabi from 200 yards away on a regular basis?

I love telling our successes, because I feel really good about them, but we have had just as many failures and mess-ups. We built a shed and farm stand this year and we got the wrong building permit and almost had to start over. We put in a moveable hoophouse like Eliot Coleman’s this year with the help of Four Season tools – but we waited too long and put it in a month late, missing our first rotation of crops. Oh, and I’m not sure if I have to say this or it’s just assumed, but we lost all of our tomatoes, a key food for the cafeteria.

Probably worst of all, over the summer we discovered that the land the garden is on isn’t actually owned by the district. We can’t be totally blamed, because the district thought they owned it, and the people who actually owned it had no idea either until they pulled up some maps. It ended up working out fine, but it was a pretty big scare for a little bit, and a pretty embarrassing mistake.

I am telling you about these mistakes because they are equally as important as our successes. Mostly, what I’m about to say is for the other youth that are here today. You’re going to mess up. Things will not always work out.

Over the winter, we were offered a $20,000 grant. That is a third of everything we have spent so much time and effort fundraising for. It is a lot of money. Project Sprout would have been set for a while, and the grant foundation really wanted to give it to us. But along with accepting the grant came changing some of our ways – losing some of our autonomy, becoming a little less student run. For the first time since we started, our board had a fight.

Now, our board is not some massive group of people who see each other twice a year. There are 10 of us, seven of which are students, and we work together, hang out together, every day. We had become a family. But some people thought we should accept the grant because we needed the money, even though it came along with letting go of some of our values, and others felt that we should be willing to give the extra time to raise the money our own way. It was the hardest time we’ve faced, and it seemed like we might be pulled apart. But eventually we realized that our values were more important than the money – that if we could not exist as an organic, student-run project, then we shouldn’t exist at all. We were an even stronger family after overcoming that fight than we had been before.

I have a close friend who is in AA, which stands for Alcoholics Anonymous. At one meeting, someone got up and said, “A good day is when everything goes right and I don’t have a drink. But a great day is when everything goes wrong and I still don’t have a drink.” Before that fight, we had had a year where pretty much everything went right and we had a garden. But after, we had had a really bad fight, and we still had a garden.

Three Stories of Sharing Food

And now we’re psyched for working with teachers from the three schools on their curriculum and tying [it] into the garden and the cafeteria. We’re pumped that it seems like some even more interesting and potentially more impactful projects are popping up all over the country. Our new goal for next growing season is to deliver food every day. The view ahead is pretty exciting.

But above all, what’s most exciting to me is this, right now. Because this weekend, we’re all together, sharing these moments of solidarity, sharing ideas, sharing stories, and of course, sharing food. I asked you to remember the last time your shared food, and here’s why. My story that began with a basket of green beans ends with the three stories that mean the most to me. And of course, they are stories of sharing food.

Throughout the summer, we donated all of the produce that we couldn’t save for the cafeteria to shelters and pantries around the county. So every Wednesday, this guy would come to the garden in his van, and we would harvest between 50 and 150 pounds of produce, load it up in his van, and he would deliver to two or three meal sites – so we were serving between one and 200 people each week.

One Wednesday, we had had a beautiful week of rain and sun – actually, it might have been the only week with sun, and the plants had taken advantage of the sunlight. Paul, the guy who comes on Wednesdays, came in his van, and that day we had a crew of about 20, and we harvested almost 200 pounds of produce. We had beets, kale, spinach, arugula, zucchini, beans, cucumbers, herbs and about five cases of chard. Paul’s van was filled pretty quickly, and by the time he left we couldn’t even see Paul in the driver’s seat.

When Paul showed up at the first meal site, a church, he went up to the door and knocked. Whenever they do dinners at that particular church, two homeless women who sometimes stay in the church have to let Paul in. They came down and opened the doors for him, and he started unloading the produce. As he walked by with baskets overflowing with rainbow chard and dark ruby beets, the two women became more and more amazed by the bounty. They began asking him about the food, commenting on how beautiful it looked, so he started to explain – about how it was grown by high schoolers, and it’s normally for the cafeteria, etc. As he continued carrying in the produce, telling the story of Project Sprout, the two women broke into tears and began to cry.

On Labor Day, Slow Food encouraged people around the country to plan eat-ins, which are pretty much community potlucks. We organized an eat-in at the Project Sprout garden. We set up tables lined up end-to-end at the back end of the garden and covered the center of each table with native wildflowers growing around the garden.

At 12, when the eat-in was supposed to start, people began flowing in. Pretty quickly, the tables were filled with kids, parents, teachers and community members. The 64 chairs were used up in the first 15 minutes, and people started spreading out in the grass.

The tables were filled with dishes made from people’s gardens and food purchased from the farmers’ market. The meals ranged from Project Sprout tomatillo salsa to chocolate éclairs made by a local high schooler.

After I felt comfortable that everything was running smoothly, I sat down in the grass with some friends. I looked around a saw the age barriers collapsed as 12 year olds passed soup to 50 year olds. It didn’t matter that a lot of us were strangers to each other in some ways – we knew we were all neighbors, and that day, we were sharing each other’s food. The sight of people filing through the paths in the garden, carrying their various bowls and platters to the tables, sitting next to people they didn’t know and laughing through mouthfuls of food still fills my head.

My last story takes place exactly where it should. In the cafeteria. And it takes place yesterday.

Before school, as we do every Thursday, we had harvested for the cafeteria. I had seen the look on the faces of the kitchen staff when we showed up with our beets and soybeans and green beans and chard and the other five types vegetables we had harvested.

It had reminded me that yeah, they get paid crap wages, but they chose that crap wage job (there are a lot of options for crap wage jobs out there) for a reason. Some part of them loved to cook. Some of the food had gone to the elementary school, some to the middle school, but the beans and chard had come to the high school. It was lunchtime, and I was walking around the cafeteria. It was very unlike the first day we had salads. There was no special excitement over the food – the food was on everyone’s trays just like any other day.

But that was the beauty of it. There was no show, no cameras, and most people weren’t talking about it. It made it so much more pure. Knowing the extra work that had to be put in to make rainbow chard, and the time it took to wash and cook raw beans. Seeing so many more faces that had worked in the garden – at least one at every table. There was a slowness to the way some people were eating – a cherishing. Not the exaggerating oohing and aahing you hear at a fancy restaurant sometimes, but just a carefulness that you don’t even see, and that someone else might not have noticed.

But most of all, I heard people congratulating each other on the food. They were not saying it to just me, as it had been that first season, but to each other. I could have spent all of lunch walking around, seeing the careful yet subtle enjoyment of the Project Sprout food.

But then I was stopped by a kid I didn’t know that well. I was pretty sure he had been to the garden once or twice, maybe in his Standard English 9 class. He was on the football team, I knew that much. He tugged on the sleeve of my shirt, and before he said anything I noticed something on his tray I had not noticed on any one else’s tray. It took me a second to realize it was tomatilla salsa, and I was amazed to see that the cafeteria staff had made it. The kid was pointing to it, and he said, “This tomatillo salsa is bomb man.”

Bomb means awesome, just so you know. That’s what sharing food is about. That’s what Project Sprout is about. And I’m pretty sure, if a kid I don’t know can tell me that the tomatillo salsa in his public school lunch is bomb, then we’re heading in a good direction.

Change – One Plate at a Time

Every once in a great while, a powerful leader appears and changes the path of history with some immense act of force. Those leaders are spotted randomly throughout history and are the ones we remember when we think of change – Martin Luther King, Ghandi, Lincoln. But those are just a few instances of change. Most of the change that has occurred throughout history was due to millions of small acts by millions of people that none of us remember.

We all know we’re hoping to make a big change. We’re asking people to drastically change their way of eating, and their way of life. But most likely, this won’t happen because one hero steps up and saves the day. It’s going to have to happen one gift of food at a time. The homeless women seeing our food in front of the church, the community at the eat-in, and the kids in my cafeteria are not enough to change the world. But there are a lot of faces here today. And I’m hopeful.

I’m hopeful that everyone here will get a chance to share food with someone. I’m hopeful that together, we can, and will, make a difference. But it might mean each of us handing green beans to strangers on the street. It might mean bringing friends to dinner, or bringing dinner to friends. We can change the world. It’s just going to have to happen one plate of bomb tomatillo salsa at a time.