|

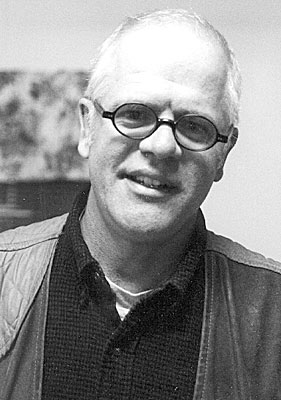

| Eero Ruutila, a featured speaker at the 1999 Farmer to Farmer Conference, talked about fast-growing greens and other ways to maximize profits on an organic farm. English photo. |

By Jean English

“The magical mesclun salad mix from Nesenkeag Coop Farm is consumed at Boston’s fanciest restaurants. It’s also consumed by the homeless and hungry population of greater Boston and southern New Hampshire.

“Such is the paradox of Nesenkeag Farm. Since its inception in 1982, Nesenkeag has straddled its double identity as a commercial organic farm and a non-profit organization providing affordable nutritious food to the poor and education on sustainable agriculture to the public.”

So begins the publicity pamphlet put out by Nesenkeag, and farm director Eero Ruuttila was fulfilling part of that education mandate when he spoke at the Farmer-to-Farmer Conference, sponsored by MOFGA and Cooperative Extension, last November.

Nesenkeag is New Hampshire’s largest organic vegetable producer, with 47 acres under cultivation. It ships more than a hundred varieties of vegetables and cut flowers all over New England, selling to restaurants, food stores, farm stands, regional wholesalers, and directly to consumers through the farm’s workplace delivery program.

Soil Improvement

Located in Litchfield, N.H., Nesenkeag is on the Merrimack River, between Manchester and Nashua, just 55 miles from Boston. The fields of this certified organic farm have very sandy soils along the river, where 2.5% organic matter is considered high (it was 0.5% before Nesenkeag), and less sandy upper fields, where an organic matter of 4% has been achieved.

Much of this organic matter is maintained by planting hairy vetch and rye as a fall cover crop, and field peas and oats in the spring. Ruuttila, who had been at the farm for 13 seasons when he spoke at Farmer-to-Farmer, has just started mixing red clover with the vetch/rye cover. He lets this mixture grow until mid- to late June, just when it begins to go to seed, then he mows it. This long growing time “gets things to full size” and gets the most nitrogen and organic matter out of them. The cover crop sits on the surface of the soil until two weeks before Ruuttila is ready to seed the ground with another crop.

After they are mowed, cover crops are incorporated using a $4,000 spader and Perfecta field cultivator rather than a rotovator. This has “cut in half the time to incorporate biomass into the soil,” says Ruuttila. The spader has eight parts that look like 8- to 10-inch-long spades and that perform a double-digging motion, going into the ground, chopping, and kicking back out at 40 degrees, so that the soil is not turned over. After the spader comes an attachment with tines, followed by a bar and rollers that smooth the bed.

The oats and peas are planted in early April, on fields that were harvested too late in the fall to have the vetch/rye cover planted, and about three seedings are possible to grow these crops into May. In addition to providing biomass, nitrogen and weed suppression, the pea greens from this cover crop “are a good source of income,” says Ruuttila. He has also planted Sudan grass, for “really good biomass,” and bell beans, “also a good biomass crop; they’re still green and alive [in November]; it takes quite a few frosts to knock them down.” The bell beans are sown in late July.

In the past, Ruuttila used stable bedding from a race track to increase soil fertility, but because he was not well set up to compost the bedding, and because it contained a lot of trash, he now maintains and has even increased the organic matter in his soil by using green manure cover crops.

Soil fertility is further maintained by liming every third year with wood ash from a power plant, and by applying sulpomag every year.

Quick and Lucrative Crops

The farm grows primarily greens, such as mesclun and “mesclun peripherals.” In fact, these crops comprise 60% of its production because they give a “quick income” – but they also “require a lot of management,” says Ruuttila. “You have to have the field ready for seeding every two or three weeks.”

Right now, “pea tendrils are very lucrative [on the] hotel and restaurant scene,” Ruuttila explained. He gets an income within 35 days of seeding from his green manure crop. The flowers and a very short part of the pea shoot can go into mesclun mixes as well, “but you get a much higher volume from pea shoots,” says Ruuttila. Shoots that are 6 to 8 inches long sell for $5/lb. wholesale and $7 directly to restaurants. He is selling 200 to 300 pounds a week.

These pea shoots, along with green garlic scallions, start the season as Nesenkeag, and are followed a couple of weeks later with the first of the mesclun mix. Ruuttila says that having people buy pea shoots from him “gets them used to buying from us by the time the mesclun is ready.” His customers include Chinese, Thai and Asian restaurants, where pea shoots are “not a garnish, but a vegetable” used in stir fries. “Chefs can build a foundation with these greens, which are quickly wilted [to maintain] their bright green color and pea flavor. Then they’re topped with meat, fish, pate … They fry them for only 20 or 30 seconds on high heat. This is a great potential market. One restaurant in Chinatown wanted 2000 pounds a week! There’s no weed management. It’s a great crop.”

The shoots are harvested by hand, by Cambodian women in their late 40s who know that when the shoots are tender enough to snap off with their fingers, they’re ready for harvest. They are harvested in the morning, when most tender, and washed (unless heavy dew has occurred). Three successive seedings are made to provide a new crop when the old shoots get tough. Irrigation also helps keep the pea shoots tender.

Twenty to 35% of Nesenkeag’s fields now grow field peas and oats, and last year the farm grossed $16,000 in pea tips. ‘Trapper’ peas from Blue Seal are used due to their hardiness and because there’s “not much downy mildew” on them.

Ruuttila plants in 3-row beds, with 15 inches between the rows, using an old Planet Junior, tractor-mounted seeder. He seeds one item per bed so that he can harrow up the crop if problems occur.

To avoid problems with flea beetles, Ruuttila doesn’t plant Chinese greens until fall.

Nesenkeag sells 80% of its produce retail and 20% wholesale. “It was the opposite,” Ruuttila explained, “but we couldn’t compete with California. We’re promoting the New England benefit – what grows best and tastes best in the New England climate at different times; what’s distinctive. It gives some anticipation.”

Other crops include spring, summer and fall mixes of lettuce, amaranth, chard, beets, New Zealand and smooth-leaf spinach, fennel, dill, thyme, pea flowers, calendula flowers, opal basil (because it doesn’t turn black when washed), arugula, purple mustard, tatsoi, scarlet runner beans grown on sunflower trellises, and more. About one-third of the farm production relates to mesclun, which generates 60% of the sales.

Weeding and Harvesting

He irrigates with overhead irrigation before seeding these crops, not just to help with germination and to avoid gaps in the availability of greens, but because moisture helps get the heat from his flame weeder into the soil. The flamer “cut in half the number of passes with the basket weeder” that Ruuttila had to make. He cultivates a stale seedbed, flames it, seeds it, then flames again for pre-emergent weed control, which “really cuts down on the in-row hand weeding” and does a great job on pigweed and lambsquarters. Ruuttila uses his intuition to tell when to flame after seeding, but says that growers could also put a glass pane at the end of a bed to promote sprouting and get some idea of when the crop will be emerging.

Ruuttila prefers the expertise of his dedicated workers, rather than machines, for harvesting. “Greens need to be the perfect height for machine harvest. My workers make adjustments as they’re harvesting. They know what to look for, and they’re fast.” They use paring knives to cut lettuce, keeping the knives very sharp with sharpening stones. “Each person harvests about 50 pounds an hour.” These workers are as much a part of the farm as the seeds and the soil. “I’m not a Buddhist, but I honor their traditions,” Ruuttila said. Thus, when they wanted to have a monk bless the fields, he agreed. They burn incense there every day as well. In return for their dedication, they are paid well: $8 per hour, with overtime after 40 hours.

Greens are washed separately in feed tanks using town water, which has a little chlorine in it. They are put in bread trays, then in a cooler – an old Star Market tractor trailer cooler that has been converted to electric and holds 18 pallets. The bread trays are stored on the pallets to provide good air circulation. Ingredients are spun dried in three used washing machines that have been wired to be permanently on the spin cycle. Seven to 8 pounds of greens are put in a machine at once and are spun for three or four minutes. Then ingredients are mixed by hand, in 30-pound loads, and from there are packed into 3-1/2-pound boxes or 1-pound bags.

Harvesters have learned to measure ingredients by the size of their palm or other ready measures. When ingredients are too large for mesclun mixes, they can be marketed individually, as baby lettuce, baby beets, and so on. Larger greens (the size of the palm plus the fingers) can be sold for $6/lb. as a braising mix. “Ten days after the mesclun is ready, the braising mix is ready. Very little gets harrowed up,” says Ruuttila. “There’s a good market for baby fennel in restaurants,” for example. Likewise, he lets some dill bolt and sells the flowers wholesale to the flower market. In a three-row bed of dill, he’ll let the middle row grow out for cut flowers.

When his greens start to “bleach out” in the summer, Ruuttila looks for reds to color his mixes. Red amaranth, for example, has a rich color, as does Medusa radicchio and Italian red ribbed dandelion.

He harvests lambsquarters and purslane – weeds growing along the edges of his fields – and sells them for $8 per pound. Pigweed is another crop.

Ruuttila has a novel method of growing potatoes: He cuts strips in the rye/vetch cover crop and plants potatoes in the strips. He hills the potatoes, then, around the solstice, he cuts the remaining vetch and rye with a brushhog and blows it onto the potatoes. “Potato beetles don’t like to navigate the straw,” he says. After using this method for a few years, he sees very strong results – even though he knows he still has beetles on the farm, because they covered his eggplants last year. They’re just not getting to the potatoes.

Regarding marketing, Ruuttila said that not only can gaps in production cause you to lose customers – hence the irrigation – but so can gaps in delivery. He said that he hasn’t missed a delivery in 13 years. “You need to be responsible,” he said, adding that he’s “gotten a lot of business from other growers not being reliable.” He delivers somewhere, five days a week, with restaurant accounts taking two of those days.

Delivery takes place in an ‘85 Ford truck that has an insulated, refrigerated box that runs off of the engine. Thus, his produce is delivered to chefs’ kitchens within 24 hours of harvest and is refrigerated until it gets to the restaurant.

Every Saturday, Ruuttila writes a weekly newsletter, which he uses to “create a story,” he said. “You’re the farmer going into the city. You’re marketing the locality of your farm.” Tell customers “what’s coming, what’s not so good any more.” The newsletter is emailed or faxed to customers.

The thorough and intense work performed by Ruuttila and others at Nesenkeag grosses $150,000 to $180,000 per year, and Ruuttila gets about $35,000 as salary.

Highway Intrusion and Pesticide Drift

Some of the farm income was spent on legal fees last year, as Nesenkeag spent $7,000 and Ruuttila attended some 25 meetings to try to stop the widening of a highway near the farm. Eventually 2 acres of the farm were taken by eminent domain.

Ruuttila was asked to comment on a spray incident that occurred in 1993 and affected his farming and his family. At that time, he lived a mile from Nesenkeag and raised transplants for the farm in his home greenhouse. When a neighboring farmer misapplied clomazone (Command), an herbicide that acts as a chlorophyll inhibitor, it left a “very visual trace of where the material moved. You could follow the drift 2 miles out of the field.”

The pre-emergent herbicide, used to kill weeds in pumpkins, soybeans and cotton, adheres to moisture in the field. As water evaporates out of the field, the herbicide drifts on the water molecules. It drifted to Ruuttila’s home and killed all of his plants in the greenhouse, as well as his animals. Ruuttila had blood in his urine, his hands shook for months, metabolites from the herbicide were found in his blood, and residues were found in his greenhouse and kitchen. His business and his reputation as an organic grower were damaged. Last spring, Ruuttila had to have his thyroid removed, and he now suffers acute arthritis and immune system problems Worst, his youngest son was a year old and nursing when the incident happened, and his family’s exposure to the herbicide continues to worry Ruuttila.

It took the N.H. Department of Public Health two months to visit the site. Eventually the 80-year-old farmer who applied the herbicide was cited with 17 violations of state and federal pesticide laws. The farmer has since died.

Because Ruuttila had had a fellowship for a year to study post-harvest pesticides, he knew how to get information about clomazone. “Every pesticide has a product manager,” he explained, “at the Office of Pesticide Programs in Washington, D.C. You can call your congressman and file a Freedom of Information Request for the entire file on a pesticide.” For anyone who is involved in a spray incident, “Give the information to a competent lawyer and to the media,” he advised.