|

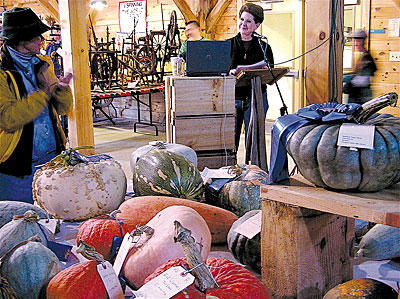

| Noted author and seed saver Amy Goldman talked about the many pumpkins and squashes displayed in the Exhibition Hall at the Common Ground Country Fair and described in her exquisite book, The Compleat Squash: A Passionate Grower’s Guide To Pumpkins, Squashes and Gourds. English photo. |

By Jean English

Amy Goldman is a passionate gardener, seed saver, author and well-known advocate for heirloom fruits and vegetables. She has been putting food on the table since she was a teenager. Among her many affiliations, she is board chair of the Seed Savers Exchange (SSE) – the premier U.S. nonprofit seed saving organization, with 11,000 members saving and sharing heirloom seed. Her books include Melons for the Passionate Grower (Artisan, 2002); The Compleat Squash: A Passionate Grower’s Guide To Pumpkins, Squashes and Gourds (Artisan, 2004); and The Heirloom Tomato: From Garden to Table – Recipes, Portraits and History of the World’s Most Beautiful Fruit (Bloomsbury, 2008).

At the Common Ground Country Fair, Goldman spoke eloquently about pumpkins, squashes and gourds of unsurpassed beauty, exceptional flavor and rare form. “I’m delighted to be at the Common Ground Fair,” she said, “where heirloom vegetables are the rule, not the exception.”

Goldman called herself a devotee of pumpkins and squashes, “so much so that my house is a shrine to the almighty cucurbita,” with decorative pumpkins and gourds and a portrait gallery of squashes. She stores hundreds of squashes in her basement storehouse, and “pumpkin, of course, is always on the menu.

“I’ve discovered what Howard Dill, breeder of the world’s biggest pumpkin, knew long ago,” said Goldman. “Pumpkins, silly things, have the power to make people happy.”

|

| Goldman is “devoted to” ‘Marina di Chioggia’ squash – yet another first-place winner in the Exhibition Hall this year, grown by MOFGA’s own Mary Yurlina. English photo. |

Steeped in Variety – and Rarity

The blue-skinned ‘Triamble’ squash was the first to catch her attention. When she grew it in her garden, “I discovered that its wall-to-wall orange flesh was fabulous, even when eaten raw like a carrot.” Now she is devoted to many more squashes, including ‘Marina di Chioggia,’ ‘Winter Luxury Pie,’ ‘Seminole’ and ‘Hubbard.’ (Many of these are pictured and are available from www.seedsavers.org.) She has traveled the world attending pumpkin festivals and tastings and collecting seed.

Goldman steeped herself in the cucurbits when she aspired to winning the Grand Champion rosette in vegetables at the Dutchess County Fair in Rhinebeck, New York. “I eventually won the grand championship with 38 blue ribbons,” she said. “Apparently no one else was crazy enough to grow zucchinis and straightneck squashes into Ziploc bags to preserve their pristine complexions.”

Regarding this experience, Goldman paraphrased Liberty Hyde Bailey: “I became aware I grew miracles. I fell in love with heirloom vegetables, treasures from the past handed down. I learned that squashes like ‘Triamble’ lead a tenuous life, available from only one or two small seed companies that could go out of business at any time. Thousands of good, old-fashioned vegetables are dead and gone, victims of a wave of consolidation in the seed industry, market forces, and the advent of first generation, F1 hybrids. Open-pollinated standard varieties represent agricultural biodiversity, which is, of course, necessary to our very survival.”

Goldman went on to win three grand championships at various fairs and to immerse herself in the heirloom seed movement. Still, she struggled with stringy, watery, smelly pumpkin flesh when carving pumpkins and resorted to cans of Libby’s when making pies. “I didn’t realize then that those punky orange pumpkin heads were more fit for livestock than as pie stock,” she recalled.

|

| Goldman called Cucurbita maxima ‘Iran’ “a showstopper” for its beautiful bi-colored skin, but its “pabulum-like taste suggests letting it sit as an ornamental.” This prize-winning specimen was grown by Heron Breen of Little Bird Farm. English photo. |

Through SSE, she learned more about squashes, “the edible members of any of the five domesticated species of Cucurbita, which is a genus native to the Americas. Pumpkins are included. They’re simply edible, round-fruited cucurbitas of any color.” The family also includes ornamental gourds, which are bitter or bland but never sugary.

Regarding taste, “we’ve got blinders on if all we see are the round orange balls of the pumpkins of Cucurbita pepo and mediocre immature acorns and butternuts. Far better to set a table with the starchy, dry, thick, flakey, floury, nutty-melting and fine-textured winter squashes, the mature squashes of some of the other species. Heirloom squashes and pumpkins are good, old-fashioned, soul-satisfying food,” providing appetizers, soups, salads, entrées and desserts. Her book The Compleat Squash includes information on growing and saving pure seed of these plants, cooking with them, and gorgeous photos by Victor Schrager of 150 “extraordinary heirlooms” that Goldman grew and evaluated over two years.

A Few Favorites

‘Connecticut Field’ pumpkins were domesticated by Native Americans, who used them for medicinal and culinary purposes, but Goldman prefers ‘Winter Luxury Pie’ pumpkin for its finer, sweeter flesh. ‘Connecticut Field’ is now used primarily for jack-o-lanterns and decorations.

|

| ‘Queensland Blue’ is one of Goldman’s favorite table squashes. Herbert Birch of Coopers Mills, Maine, grew this beauty and earned a Judges’ Award in the Exhibition Hall at Common Ground. English photo. |

“Show me a squash with warts and boils, and I’ll show you the way to my heart,” Goldman continued, as she showed a photo of ‘Marina di Chioggia.’ “Her blue-green armament of blistering bubbles simply does things to me.” Goldman finds this variety not only oddball but “deliciosa.” Originally from South America, ‘Marina’ now “lives and thrives in the salt air and sandy soils of Chioggia, the Adriatic port famed for its vegetable and fruit market, located at the southern tip of Venice.”

‘Sucrine du Berry,’ although fibrous, cooks up beautifully, said Goldman, especially when roasted or baked, with stunning, deeply and intensely red-orange flesh. It also makes good chowder.

For size, Cucurbita maxima are the behemoths – the biggest fruits on earth, said Goldman. They aren’t especially good for eating but are “the new fat lady” of circus-like giant pumpkin festivals, weighing well over 1,000 pounds. Giant pumpkins are direct descendants of ‘Jaune Gros de Paris,’ or ‘Large Yellow Paris.’ In her talk and book, Goldman traced its history from France to the United States, where Henry David Thoreau first grew it. “Today, Howard Dill of Windsor, Nova Scotia, is the pumpkin king” for having developed ‘Atlantic Giant,’ “the world’s biggest pumpkin,” said Goldman.

At the other end of the spectrum is ‘Jack-Be-Little’ – which some believe is actually an acorn squash. “‘Jack-Be-Little’ tastes like an acorn,” said Goldman. “These are not just for ornament.”

‘Nest Egg’ gourds can be placed in hen houses where you want hens to lay, getting hens accustomed to the idea of laying in those places. They can also encourage hens to set on fertilized eggs. Put the gourd in the hen’s nest, and when the hen gets the idea, replace the gourd with a fertilized egg. “Just remember to snap off the stems,” said Goldman, “or you’ll be goosing your chickens.”

Regarding ‘Hubbard’ squashes, “we should all get down on our hands and knees and thank James J. H. Gregory for introducing the original green Hubbard to the American public 150 years ago,” said Goldman.

Zucchini, now the most popular squash in the world, was virtually unknown 100 years ago, Goldman continued. It was first grown in Italy in 1901, and was likely brought to the United States by Italian immigrants. Goldman showed two ways to use zucchini: as a filler for quiche, and as a crust for pizza.

‘Iran’ squash (or ‘Empress of Persia’) is a showstopper for its beautiful bi-colored skin, but its pabulum-like taste suggests letting it sit as an ornamental; it remains intact for up to two years.

Harvesting and Curing

Goldman prefers harvesting squashes a little early rather than leaving them to the vagaries of frost and chilling damage, insects and diseases. Once they have reached their maximum size and have started to color up, bring them in to cure at a temperature in the 70s, if possible.

“If you are kind to your pumpkins, they will reward you with a long shelf-life. Be careful to minimize stem injury, since a damaged or missing stem is an open invitation to pathogens. Dropping, throwing or stacking pumpkins can bruise them, so lay them down gently and treat them as if they were eggs.”

Goldman suggested curing pumpkins and winter squashes for two to three weeks in a well ventilated place out of direct sun to heal wounds and toughen rinds, enhancing their storage life. She cleans and bathes hers in a 10 percent chlorine bleach solution before curing them, to reduce surface contaminants. After they’re cured, store them between 50 and 60 F with a relative humidity of 50 to 70 percent – conditions often found in basements. Well prepared squashes and pumpkins will store for three to six months before decaying, becoming sweeter during storage, as starches turn to sugars. “For sheer endurance, the cheese pumpkins are peerless,” said Goldman.

Among her favorite table squashes are ‘Queensland Blue,’ ‘St. Petersburg’ and ‘Blue Banana’ types. ‘Winter Luxury Pie’ “makes the most velvety pumpkin pie I’ve ever had.

“I could go on and on,” said Goldman – and her book will take readers on and on, into a spectacular world of cucurbits that deserve to be conserved.