|

| Organic blueberry grower Doug Van Horn, left, and insect ecologist Frank Drummond, Ph.D., of the University of Maine, Orono, stand by a newly installed native bee nesting box at Twitchell Hill Blueberries in Montville. Lynn Ascrizzi photo. |

|

| A leafcutter bee (Osmia atriventris), commonly called the Maine blueberry bee, forages on blueberry blossoms. This native bee, and other important wild pollinators, help offset the recent die-offs of honey bees, called colony collapse disorder. Frank Drummond photo. |

|

| One of 18 hand-built, native bee nesting boxes installed at Twitchell Hill Blueberries. Lynn Ascrizzi photo. |

Native bees are big part of Maine blueberry grower’s pollination plans

By Lynn Ascrizzi

Last summer blueberry grower Doug Van Horn launched a one-man agricultural experiment to boost pollination and production on a 15-acre organic wild blueberry field located at Twitchell Hill in Montville, Maine.

Van Horn, who lives in nearby Freedom, has been tending the fields for roughly 35 years. But for a couple of seasons, his fields had not been producing well.

“It got me to thinking about the whole pollination thing,” he said. So among a few other field improvements, he began a project to attract native pollinators, commonly referred to as mason bees.

“It’s a tiny bee. It looks like a bee, but it’s the size of a housefly,” said Van Horn. But size doesn’t matter when it comes to these hard-working wild pollinators. “Mason bees are about four to five times more effective as spring-season pollinators than honeybees,” he said.

In fact two native species in particular – mason and leafcutting bees – are associated with Maine blueberry fields, according to insect ecologist Frank Drummond, Ph.D., of the University of Maine in Orono. Both bees, collectively called megachilids (mega kyle’ lids), are important pollinators of blueberries, he said. For instance, there’s the leafcutting Maine blueberry bee (Osmia atriventris), which seals its nest hole with chewed leaf matter. Mason bees, such as Osmia lignaria, cap their nests with mud.

Both species are short-lived and solitary. In the wild, they build nests inside hollow reeds or holes left by wood-boring insects. Osmia bees, unlike the honeybee, do not create colonies of busy workers that produce honey and beeswax. With no hive or honey to defend, they are unlikely to sting, and their sting is mild, Drummond said.

To lure these productive little bees to Twitchell Hill Blueberries, Van Horn had a local woodworker create small, odd-looking wooden nesting boxes made of pine, hemlock and basswood. The variously designed boxes, roughly 8-by-8-inches in size, were comprised of a cluster of 20 individual wooden tubes. Tube holes were drilled about 1/4-inch in diameter (UMaine recommends 5/16- to 7/16-inch, depending on the bee species), and each tube was shellacked to prevent raw wood from absorbing moisture from food that mason bees deposit inside the tubes for future larvae.

Last March, Van Horn attached the newly made boxes to small trees growing around the edges of his windswept fields. “The bees go into the holes, lay eggs and deposit nectar and pollen, before they seal off the entrance. The eggs turn into larvae, and later, the larvae spin cocoons, which overwinter. In spring, they emerge as a fully mature bee,” he said.

Nesting boxes of various designs for wood- and cavity-nesting bees are available commercially; Van Horn did extensive research to incorporate what he hoped were the most practical designs. For instance, his boxes were created with whimsical variations. “Mason bees don’t like order. They like more random designs,” he said.

Why so much interest in native bee pollinators?

“There is renewed interest because of problems with honeybees caused by Colony Collapse Disorder,” Drummond said, referring to worldwide die-offs of honeybee populations, first noticed in 2006. “It’s caused, in part, by bees being exposed to pesticides, viruses, fungal pathogens, parasitic mites and poor diet,” he explained.

After trialing his nesting boxes for one season, Van Horn was delighted to find evidence of mason and leafcutter Osmia bee activity.

“Overall, it looks like the boxes are attracting the bees. About 50 percent of the nest-box holes had some sort of insect or bee in it,” he said. “I could tell, because the holes were plugged up. Some I know for sure were mason bees, because they have a clay-type plug to the hole. Some (plugs) looked like chewed-up leaves. So I think they might be leafcutter bees.”

Last winter, he brought all the nesting boxes indoors and put them in a cold, unheated section of a house at Twitchell Hill to protect them from woodpeckers.

Out of curiosity, he opened several tubes. “I clearly saw larvae inside. They looked like mason bee larvae. Then I taped up the boxes, hoping I didn’t disturb them. We’ll see if they emerge in late April,” he said in early March.

In one nest box he discovered other wild tenants. “One tube was full of ants. That’s why some people remove the (bee) larvae from the tubes and overwinter them, to protect them,” he said. Van Horn just cleaned out the ants. The nesting boxes were returned to the field in March.

After the bees emerge, he planned to drill out the used tubes in the nesting blocks and shellac them again for the next nesting season. “Too much time taken to husband the nests may not be worth it,” he said. He also evaluated nest-box designs. Those built to be split in half, so that tubes can be accessed easily to remove larvae or other insects lodged inside, seemed the best option.

Beyond Blueberries

In early spring 2012, Van Horn and Drummond inspected the blueberry fields at Twitchell Hill and the newly installed boxes.

Strategically placed nesting boxes (also called blocks) of the right design will attract native Osmia bees, Drummond said. “It may take a year before you get the full results. A UMaine study in the mid-1990s showed a fourfold increase of Osmia bees in blueberry fields that had nesting boxes. Fields without nesting boxes showed a decrease in native bee populations,” he said.

These little insects pollinate other crops, too, he noted.

“Osmia bees pollinate apples, wild cherries and sweet and sour cherries, especially in southern Maine. They pollinate highbush blueberries, cranberries, raspberries and blackberries. But, not so much on strawberries. Spring fruit crops that bloom in May and June – Osmia bees will take care of them,” he said.

|

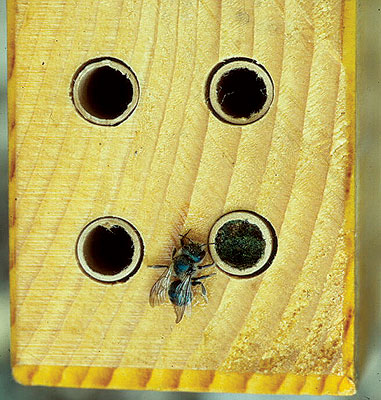

| A native bee on a nesting block. Frank Drummond photo. |

Maine has plenty of native bee pollinators, he added. “You can buy some Osmia bees, commercially, such as Osmia cornifrons, used in Michigan to pollinate cherries, and the blue orchard bee (Osmia lignaria), both sold in the U.S. But we have 17 different, native Osmia bees in Maine. People don’t need to go out and buy them. We can encourage them by installing nests, providing habitat and building up their numbers. And they’re better adapted to our climate.”

Native bees tend to nest in locations with southern and southeastern exposures. Farmers and gardeners can put nest blocks 30 to 50 feet apart around the edges of their property, he said.

“It’s more of a rule of thumb. The number of boxes varies for people who have lots of standing dead trees on their property or lots of shrubs with soft tissue in them, like raspberry canes. This increases the chances of bee nesting sites. Osmia bees tend to be an edge-nesting species. But if coniferous forests surround the property, there’s not much nesting habitat. Then you might want to place more boxes,” he said.

He also advised hanging nesting blocks at eye level and higher. “The bees don’t occupy nests as much if boxes are placed knee high. During the spring, when there are lots of insectivorous birds in the field, hang aluminum pie plates above nesting blocks,” he said.

According to UMaine statistics, Van Horn is one of about 50 wild-blueberry growers farming organically. Altogether, Maine has about 600 blueberry growers. Only about 20 Maine blueberry growers provide nesting boxes for native bee pollinators, Drummond said.

“I’d like to see a lot more. And not just nest blocks. I’d like to see more growers encourage native pollinators by selecting pest management strategies that reduce exposure of bees to insecticides and enhance flower sources,” he said.

He began working with organic blueberry fields about 10 years ago. Out of 65,000 acres of blueberry fields in Maine, about 400 acres are farmed organically. “But it’s not just organic growers who are encouraging pollinators. Some conventional growers are planting pollinator strips too,” he said. However, organic farming and gardening techniques offer safer support for native bee populations, he noted.

“Organic farms tend to have a greater diversity of plants. Since organic farmers are not using herbicides, farms with greater floral diversity have a greater diversity of bees, in general. And, the more pesticides applied during the growing season, the fewer the Osmia bees. Also, smaller bees are more susceptible to pesticides. There are approved organic insecticides, but some are lethal to bees. Growers that aren’t using insecticides at all, or who use them very minimally, will provide a safer environment for bees.”

Win Some, Lose Some

Ironically, despite Van Horn’s success with attracting native bees, his blueberry yield last summer was disappointing. “About half the blossoms got pollinated, but then a big wind and rain storm blew off the remaining blossoms before the bees could pollinate them. We got maybe one-third of what I expected, although I didn’t rake all of them, because the berries were sparsely distributed and time-consuming to pick,” he said.

His native bee nesting box project was funded, in part, by a $4,300 grant he received last year from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) program.

“They have a program for organic growers to improve organic farming operations,” he said. The federal grant provided funds to create an access road to the blueberry fields, to remove weed and brush growth, to plant pollinator-attracting native plants and to create 10 mason bee nesting boxes. He fulfilled those goals and more, creating 18 nest boxes.

“If not for that help, I wouldn’t have been able to take care of the fields as I did,” he added. For example, his weed control improved. “Three times in a season – June, July and August – I weed-whack everything taller than a blueberry plant and essentially defoliate trees and weeds, without herbicides. I can see the blueberries better, and more sun gets in to the buds,” he said.

A retired Unity College math professor, Van Horn owns the blueberry field collectively with a handful of friends who once lived communally in a large, hand-built, wood-and-stone house set on 70 acres of woods at the end of Twitchell Hill Road.

“Blueberries are my own personal project at Twitchell. They were there before I arrived in 1976,” he said.

Resources

Field Conservation Management of Native Leafcutting and Mason Osmia Bees, Fact Sheet No. 301, UMaine Extension No. 2420, by C. S. Stubbs, F. A. Drummond and D. E. Yarborough. https://umaine.edu/blueberries/factsheets/bees/301-field-conservation-management-of-native-leafcutting-and-mason-osmia-bees/ .

“The Blue Orchard Bee (BOB): Optimizing Fruit Tree Pollination for Maine Orchards,” by Adam Tomash, The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, March-May 2013. www.mofga.org/Publications/MaineOrganicFarmerGardener/Spring2013/BlueOrchardBee/tabid/2552/Default.aspx

About the author: Lynn Ascrizzi lives and writes in Freedom, Maine.

|

Resource “Farming for Bees: Guidelines for Providing Native Bee Habitat on Farms,” by Mace Vaughan, Matthew Shepherd, Claire Kremen and Scott Hoffman Black. 2007, The Xerces Society. This 43-page booklet is available as a free PDF download or for purchase ($15) at www.xerces.org/guidelines-farming-for-bees/. |

Bee-Friendly Plants

Besides introducing native bee nest boxes to his Twitchell Hill blueberry fields in Montville, grower Doug Van Horn also planted a half-acre strip of perennial wildflowers adjacent to the fields to attract native and non-native pollinators, such as mason bees, sweat bees, honeybees, bumblebees, cellophane bees and others.

Van Horn used a mix of perennials and self-seeding annuals designed by UMaine graduate student Eric Venturini, who is continuing the study this year. Seeds were donated by Applewood Seed Co. of Arvada, Colorado.

Venturini “worked out a planting of perennial plants that would not overrun a blueberry field and would blossom when blueberries don’t blossom, such as coreopsis, lupine, wild sunflower, purple coneflower, Indian blanket, bergamot and New England asters. We used an unproductive, south-facing blueberry field and tilled in lime to offset the low pH of the field,” Van Horn said.

Results were mixed last summer. “The seeding worked well in some areas and not in others. Ferns came up and shaded the perennial seedlings. It’s not yet successful, unless some of those plants re-emerge this season and take over,” he said.

– – – –

Many native and non-native flowers, trees and shrubs attract a diverse array of native pollinators over an entire growing season. Some of these bee-friendly plants are listed below by their common name and arranged in order of bloom period.

Spring

- Alternate-leaved dogwood

- Apple

- Blueberry

- Chives

- Chokecherry

- Daffodil

- Dandelion

- Plum

- Red maple

- Shadbush/serviceberry

- Wild black cherry

Early Summer

- Borage

- Horsefly weed

- Red clover

- Rose

Midsummer

- Boneset

- Culver’s root

- Joe Pye weed

- Lavender

- Northern evening primrose

- Oregano

- Purple coneflower

- Purple lovegrass

- Sage

Late Summer

- Goldenrod

- New England aster

Source: Applewood Seed Co.