By Jean English

|

| Michael Zuck gave an inspiring talk at MOFGA and Cooperative Extension’s Farmer to Farmer Conference about using teosinte and other plants as “banker plants” in greenhouses – plants that support pests that, in turn, support beneficial insects. English photo. |

Michael Zuck’s fascination with nature’s multiple interactions, combined with the fact that his wife developed severe multiple chemical sensitivity a few years ago, are polar but complementary forces that have made Zuck pursue biological pest control with determination. In his nineteenth year with the business that he and his wife own, Everlasting Farm in Bangor, Zuck has “had fantastic successes and dismal failures in almost equal balance” as he’s experimented with biological control.

Everlasting Farm sells floricultural crops and herb and vegetable seedlings in the spring. Ninety percent of the income comes in between May 1 and June 15; so this year, the farm will not even be open in July and August. “It’s not worth it to squeeze out that last 10 percent,” Zuck told participants at MOFGA and Cooperative Extension’s Farmer to Farmer Conference in Bar Harbor last November.

While their business may be open for only six weeks, the Zucks keep hundreds of stock plants year round, “so this means we grow our own bugs, our own pests, on a year-round basis. So we have very different challenges from, say, organic vegetable growers who may have an empty greenhouse” in the fall and winter. Zuck describes his operation as “a big petri dish. We roll up the sides of the greenhouse in summer and we just say to Nature, ‘What have you got?’ And that works both ways – we have beneficials coming in, but we also get lots of pests.”

Zuck tries to get pests under control in the fall by “scouting, scouting, scouting, which to me is kind of like meditation. There’s nothing I’d rather do than walk around with my hand lens and look.” His 10x lens “is my little rosary.”

If the lens is his rosary, beneficial “bugs” are the indulgences he buys to turn his greenhouse into a piece of Nature’s heaven. He buys these primarily from The Green Spot in New Hampshire (see Resources) and refers to The Green Methods Manual, written by Michael Cherim of The Green Spot, as “the commercial bible as far as information goes. It’s very well organized and quite funny.”

In addition to this bible, Zuck was inspired at a day-long course put on by Cooperative Extension at Longfellow Greenhouse in Manchester a few years ago. These resources added a whole new level of interest to his business, said Zuck.

The first year Zuck implemented biological control, “I was pretty much on top of whiteflies and thrips, but aphids were an ongoing concern for us.” He has all natural ventilation in his greenhouses. “There’s no way I would even consider using microscreening [a physical barrier to exclude pests from greenhouses], simply because we rely on a very gentle, passive movement of air through the roll-up sides and out through the ridge vents of our greenhouses, and I just can’t see spending the money to power ventilate…” However, roll-up sides also admit aphids. “They are early pioneers. You can get through January, February and March in pretty good shape and still get clobbered if you have a greenhouse full of fuchsia baskets.”

Adventures with Banker Plants

Zuck learned about banker plants at the Longfellow conference. These plants shelter aphids and the wasps that parasitize them and offer a way of transporting beneficial insects to “hot spots” in the greenhouse. Zuck’s alternative was to order a small, $40 vial of aphid parasitoids for each of his eight greenhouses each week. “That’s $320 a week. It was a no brainer to me.”

So Zuck started Niagara Giant pepper plants (from Stokes) around the first of February, because peppers are “about the best thing to raise [for aphids]. I didn’t have much trouble getting the aphids to go to them.” He built small tents of Reemay and framework to hold the aphids in, put the parasitoid wasps in the tents, and “basically forgot about them for two weeks.” When he rolled the Reemay back, “Voila! They were covered with aphid mummies. That first year we had better control of aphids in our greenhouses than we had ever achieved.”

The following year he started his peppers on January 1 instead of February 1, “and could I get aphids to go to those pepper plants? Absolutely not!” This was a different variety of pepper, which may have been the problem. “Finally I went to the University of Maine and found some people who were working on the green peach aphid, and they supplied me with abundant aphids. So I put the aphids on the peppers. Would they proliferate? Absolutely not. So it was a dismal failure, and I have no explanation for that. The only way I got through the second year was that I had this huge Bougainvillea plant that was a banker plant all by itself. And that’s the beauty of this whole system: If you learn when to stand back and let Nature take over, wonderful balances have a way of asserting themselves. So I spent the second year just transporting this Bougainvillea around the houses, sort of limped through with not as much comfort level as I had the first year. It does take nerves of steel to do this, because you’re allowing aphids to proliferate… It changes your perspective 180 degrees when you see aphids in the greenhouse… I say ‘hee hee!’ and if I need to, I’ll order some parasitic wasps.” He finds that Aphidius matricariae is the most effective wasp against the green peach aphid.

After mixed success with establishing banker plants, Zuck was visiting the greenhouses at the University of Maine when the manager there, Brad Libby, showed him a teosinte plant. Zuck learned that this ancient relative of corn was rediscovered about 25 years ago by a botanist in the highlands of Mexico. The plant looks like corn but has rhizomes and is perennial. Breeders have been hoping to use its genes to make perennial fodder corns for southern climates.

Libby’s teosinte was 8 feet tall and was making seed heads. He told Zuck that he could find aphids and mummies on the plant any time of year, so he never sprayed it and it provided a constant source of aphids for beneficial insects. “That’s the golden high,” said Zuck. “That’s what we’re looking for. The whole trick with this system is to try to balance it so that the parasitoids don’t put the aphids out of business, and the aphids don’t put you out of business.”

Zuck recalled learning that Europeans can buy banker plants of barley that are infested with a cereal aphid that doesn’t bother floricultural crops but does feed parasitoid wasps. Europeans claim six weeks of protection in their greenhouses from the barley-aphid-wasp ecosystem, but the insect-inhabited banker plants cannot be shipped to the United States, because they’re too big and perishable, and “because it’s very hard to convince the authorities to let you ship a pest,” said Zuck. Ironically, he added, most people don’t realize that virtually all beneficial insects sold to growers in the United States come from Europe. “When you call up The Green Spot and order them on a Friday, they book an order right then with one of the European firms. They come across the Atlantic on the weekend to The Green Spot, and I get them on a Wednesday.”

Zuck is trying to grow banker barley himself. “I’d like to be the first person to introduce barley bankers to this country. I don’t know how serious I am. If somebody wants to take this ball and run with it, I wouldn’t chase you. I’m here to share.” He urges anyone who has any interest in this topic to contact him.

In January of 2002, Zuck started some barley and got aphids from Libby’s teosinte plant. “I did not know at this time if it was a cereal aphid. I was just putting two and two together. Teosinte is a cereal grass, and I knew that in Europe they had cereal aphids.” He was unable to get the aphid identified in Maine, partly because “the aphid collection that had been preserved by the great Edith Patch, the legendary entomologist at Orono, had been shipped to McGill and would be there forever.

“So I had to take a big risk, going to the University and getting this population of aphids and introducing them into my greenhouse just on the faith that they hadn’t bothered Brad’s plants. So I put them on the barley and put them in big plastic boxes with Reemay over them, and they took right off – covered the barley plants… But I’m still very nervous; my stock collection is more than 600 species, widely varying – tropicals and desert plants – so it’s the perfect opportunity to get in trouble by introducing a new organism. So I kept them as carefully contained as I could. It’s pretty hard to keep aphids in, because they make winged flyers, and they’re always trying to get out.” Unfortunately, his boxed barley produced such a moist atmosphere that mold became established and the aphids died.

Zuck started more barley and eventually got a banker plant system that enabled him to “limp through” the year by moving the banker plants to aphid populated areas of his greenhouse. “I had one fabulous demonstration of the power of this system; I had bought in a large crop of Spanish lavenders, potted them up, and they seemed fine.” He put them in one of his 30- x 100-foot greenhouses that attaches to the head house. This house had no aphids that he knew of, but about a month later he realized that the lavenders themselves had brought in aphids when he “spotted them just everywhere. I panicked because I hadn’t had any protection.” His only banker plants were in another greenhouse that attached to the head house. But he looked a little closer and realized that the parasitoids had already found the aphids. “They’d flown through the head house and pounced on them. It’s a very powerful system.”

He then started teosinte using seeds from Libby. “Things got busy in the greenhouse. I had these teosintes for future reference. I put them as far from everything else that was going on as I could. Those cereal aphids sniffed those [teosinte plants] out, and the flyers found them 150 feet away. By the time I got around to paying attention to them, they were already fully colonized with the cereal aphids and the parasitoid wasps. I concluded: This is a natural system that is just dying to balance itself. All you provide is the house, and everything else will take care of itself.”

Because teosinte grows to be 8 feet tall, Zuck did not believe it was very shippable, so he decided to try growing sweet corn to a shippable height and seeing if he could get the aphids and parasitoids established on that. “I had huge success with teosinte last summer; after the barley plants had gone to seed and were essentially defunct as banker plants, I was able to rely on my teosinte plants. I put them wherever I had problems and never had an aphid infestation anywhere.”

By the end of the summer, the teosintes were “horribly potbound.” Zuck repotted them and put them on the floor of his stock house in a sunny spot, and “the earwigs pounced on them. Everywhere I’m accustomed to seeing aphids, which is in the tightly wrapped whorled leaves of the tip, there was an earwig by the end of summer. They had completely kicked [the aphids] out or eaten them or whatever. I actually had to go back to Brad this fall and get more aphids.”

He put the aphids on the sweet corn, “and they went into the tightly wrapped whorled leaves. I believe that is the key to the system: The physical shape of this plant is perfect for providing a constant source of aphids. Aphids are reproducing right down in the tightest cleft between the leaves. They’re sort of burbling up all the time as they grow, and the parasitoid wasps are polite enough that they just eat the ones that burble up and leave the breeders down below alone.”

When he put the aphids on the sweet corn, however, they quickly grew wings and vacated, looking for better habitat. Zuck hypothesizes that the newer breeds of sweet corn have had some very important genetics bred out of them. So “at this point I’m stuck with barley, which kind of works, and teosinte, which really works.” He has only a tiny seed crop of teosinte, not enough to share, “but I’m very willing to share aphids at any time,” he quipped. He is hoping to study ornamental grasses as potential banker plants, too. [An Internet search showed that Abundant Life Seed Foundation carries teosinte. See Resources.]

“Teosinte really is a neat plant,” he continued. “It flowers on the tassels on top; it has no ears on the side. The tassel has male flowers on top and female on the bottom. It makes a little ear, like a one-wrapper husk, with a tiny chain of energy-packed grains in there. You can just imagine how it would have excited the Indians as they came down from Alaska and found this fairly lush grass they could pound into flour. So I’m enjoying just having the relationship with the plant for that reason.”

Other Pests

Zuck pointed out that in order for most biocontrols to work, your greenhouse must maintain a certain temperature and relative humidity, as noted under each listing in The Green Methods Manual. Beneficial wasps, for example, are cold-blooded creatures, “very delicate little wasps,” who are not happy below 65 degrees, so working with them through the winter can be challenging. Because Zuck maintains a lot of stock plants in a small area, he can maintain 65-degree night temperatures and a high relative humidity. He also uses some supplemental lighting from a 1000-watt sodium light when the days are short, because aphids don’t make winged forms during short days and without supplemental lighting, their populations crash. Growers raising crops in greenhouses or tunnel houses in other seasons will have a different perspective.

Regarding thrips, Zuck has used Neoseiulus cucumeris but with little demonstrable control, as others have also noted. He has not tried to control the pupal stage in the soil with the soil mite, but he has resorted to Conserve. “Use Conserve and you don’t have thrips,” he said. “With my stock collection, I was not prepared for how different my plants looked after I controlled thrips. They were in there hammering away at everybody pretty much. Plants that had acceptable growth suddenly had spectacular growth.” Conserve is very expensive – $150 per quart – but a very small amount (3/8 tsp. per gallon) is needed, and the re-entry interval is four hours. “I’ve learned to share with people to keep costs down,” said Zuck. “But if you’re maintaining plants year-round, it’s the only way to go.”

He added that a Canadian company has a “super high powered garlic and soybean oil product they claim is a very good irritant of thrips. That’s half the battle with thrips: to get them to come out so you can do something to them. They’re in the tiniest, tightest little clefts of foliage. You just can’t get at them with any spray.” He will try the garlic product and thinks it may be useful on onion crops, too. “If there’s any way to drive [the thrips] out, you can hit them with Safer Insecticidal Soap or something.”

Learn to see the very beginning of thrips’ damage, Zuck added, such as curly tips and flower petals with streaking coloration. “You can take a double impatiens, shake the flower cluster in your hand, and they’ll fall out.” Colin Stewart of the University of Maine Cooperative Extension said that he finds the “dragon breath method” useful: Breathe into a flower so that the carbon dioxide in your breath flushes out the thrips.

Two-spotted mites are “a snap to control” with beneficial mites, according to Zuck. He doesn’t even think about two-spotted mites. “If I see them, I know that they’re going to self-control.”

Cyclamen mites are another story. “I got tangled up with those this spring for the first time. They are the mite from hell. They’re so small, they drift on the air. Their host range is infinite. They cause absolute unsalability of plants. I spent a lot of money on Neoseiulus californicus.”

He has used nematodes to control fungus gnats and shore flies. “Don’t wait until they’re out of control, because you’re not going to get them back in control.” The nematodes must be kept in suspension as they’re applied. Zuck puts a paint mixer on an electric drill and suspends the drill over a 5-gallon bucket of the nematode solution, running the drill at low speed. He has also used Gnatrol in the summer to knock these pests down. This formulation of Bacillus thuringiensis is conveniently applied with a fertilizer injector.

Zuck has not had success with the fungus Beauvaria bassiana, sold as BotaniGard and Naturalis-O, to control aphids, and he has had serious problems with phytotoxicity when he used Naturalis-O as an emulsifiable concentrate in oil. The powdered form was less toxic.

“I like neem extracts,” Zuck continued, but neem oil can be phytotoxic to anything with fuzzy or tender leaves. “So I’ve resorted to Neem extract – Azatin – which unfortunately is in a petrochemical carrier, but we use such a small amount of it. It’s quite volatile. After a day or two, it is quite volatilized. (He has since found a formulation of Azatin from the Green Spot that has no odor, and is using that.)

Neem extract solved a pernicious whitefly problem that Zuck had one November, after trying every other control listed in The Green Methods Manual.

During the discussion section of his talk, Zuck noted that Asian ladybugs have a very poor track record in the greenhouse. They’re hard to keep in the house, filtering out through cracks.

|

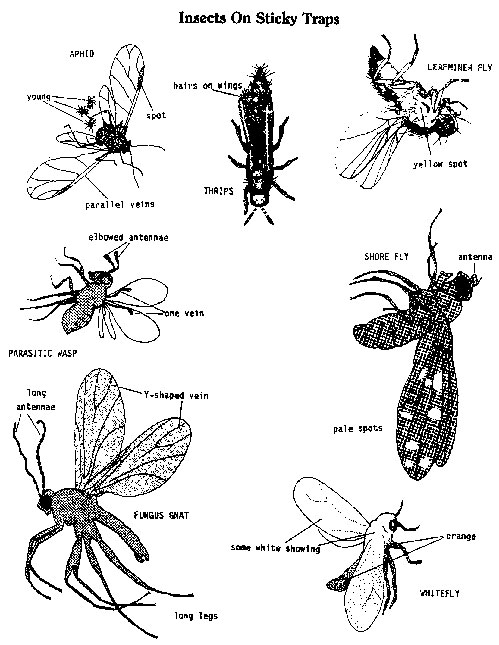

| These are some of the pests – and a beneficial, parasitic wasp – that may be found on sticky traps. Zuck pointed out that sticky traps should not be left in the greenhouse very long, since they do kill beneficials. Illustrations from “Identifying Insects on Your Sticky Cards,” by Dr. James R. Baker, Extension Entomologist emeritus, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C., used with permission of North Carolina State University. |

Scouting Tips

For scouting, Colin Stewart recommended using an Optivisor, a magnifier that you wear on your hat and pull down as needed. It comes with a 10x magnifier and can be adapted with a side lens to go up to 20x. Zuck recommended an 8x monocular sold for bird watching, from Haverhills.com, that has a screw-in piece taking it up to 30x magnification, “so it’s as good as a dissecting microscope.” He got one for about $60 to look for cyclamen mites.

Anyone who is using biological control, said Zuck, should use yellow sticky cards to monitor pest populations only one day per week, at most, and preferably one-half day per week; otherwise, too many beneficial insects will be caught. Stewart added that the thresholds of pests on sticky cards will vary among growers, greenhouses and crops. “It depends on the potential for things getting out of control.”

Sticky cards can be used repeatedly if little pest activity is occurring. Simply circle insects that you find one week with a marker so that you don’t count them again the following week. As cards lose their stickiness (after about a month), discard them. Use a minimum of one card per 1000 square feet; one per 250 square feet is better. Use yellow cards for white flies, fungus gnats, aphids and thrips, but if you’re particularly concerned with thrips, use blue. Cards should be just above the plant; you can put stakes in pots and attach the cards by clothespins. Don’t move stakes from one plant to another, Stewart warned; moving may spread disease. Do keep them in the same place each week for valid comparisons. “I’m a little dubious about how good [sticky cards] are for shore flies,” said Stewart, “unless you put a couple of them horizontally; that’s supposed to be good for catching fungus gnats and shore flies.”

Zuck finds that aphids are the “scariest” pest for him, “because they can get out of control faster than any other bug. Whiteflies build up slowly. If you let them, it’s your mistake, because sanitation is the first line of defense. We spend hours just picking off leaves that have whiteflies on them.

“Look for indicator plants,” Zuck continued. “If you have peppers and you’re not visiting them once a day, you’re missing half the show right there.” If your eyesight isn’t great, he suggested bringing glasses along or finding an employee who is interested in scouting and has good eyes. “I’ll give them an hour and have them look each day,” he said of such employees, but generally, “we just look automatically.” He turns up leaves, looks at new growth. “For green peach aphids, never look at old growth; always look at the tips.” Likewise, he can scan a fuchsia basket from the floor and tell if one leader has aphids. Stewart recommended training employees to look for problems while they’re watering.

Asked about moving plants outdoors if pests are found, Zuck acknowledged that you can shock aphids that way, and you slow down plant growth, reducing the amount of succulent tissue that aphids prefer. Also, when plants are moved outside (or when sides of greenhouses are rolled up), syrphid flies (hover flies) often appear to control aphids. “They’re right there the first of the year; they clean up the periphery.” The larvae of syrphid flies, said Stewart, are like little slugs “thrashing around in the middle of the aphid colonies. Sometimes they’ll also put the cadavers on their back.”

Regarding viruses, Zuck said that tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is an issue. “If anyone is handling Super Petunias, such as Wave petunias, and you have anybody smoking cigarettes, keep 100 yards between them and the plants.” He threw away 675 plants once because the person who transplanted them smoked cigarettes during the lunch break and infected them. “Eighty percent of tobacco is infected with tobacco mosaic virus,” Zuck added. “It’s very persistent on your fingers if you’re a smoker. Even if you smoked the night before and washed your hands normally and you’re handling some gooey crop like tomatoes or petunias, it just comes out. We’ve had unexplained problems with Gerbera daisies, and that’s very TMV susceptible. Marigolds take a very light infection, and they just don’t perform well. Last year we had no smokers transplanting, and we could see the difference. If you have to have smokers transplanting, the way to neutralize TMV on their hands is to wash their hands in milk.”

Stewart said Calypso, Super Blue Magic and Summer Magic Super Petunias are indicator plants for the virus and for thrips that carry it. He recommended scattering Calypso throughout a crop, cutting its flowers off to force thrips to feed on foliage, and hanging a large blue plate from the top of the greenhouse so that it hangs just above the plants, attracting thrips. “If you’ve got thrips that have the virus, you want them on that plant. They feed, and within a short time you see a diagnostic sign. You can get rid of that leaf; it lets you know you do have the virus in the greenhouse.” The virus is not systemic (moving throughout the plant) on these petunias, as it is on fava beans, which, therefore, he does not recommend as an indicator plant.

Leaves infected with TMV look lighter green or yellow; the color change can be subtle. When Zuck had TMV on Super Petunias, “they just didn’t grow. The foliage turned slightly purple, and there was virtually no root development. You could just pull them up after two or three weeks. In a full-blown infestation, you will get mosaicing so that the foliage looks flecked with green and yellow patches.” Sanitation can help; TMV persists in dry, leafy residue or in fresh plants, but not on surfaces in the greenhouse.

To monitor fungus gnats, said Stewart, put potatoes slices on top of benches or planting media and lift them after a few days to look for activity under them. French fry shapes stuck into the media work, too. Fungus gnat larvae have black heads. Get rid of the potato slices once a week, as they rot.

Zuck mentioned that Ageranthemums (Boston daisies or Marguerite daisies) make good banker plants because they attract green peach aphids. “You can trim them into a bush and have a nice big chunk of surface area, and the minute you know you have aphids and a host in a stable symbiosis of parasitism, that’s the minute you should have your Aphidius present. If you have the facility to be in year-round production, even on a small scale, you need to take charge of this instead of trying to predict it. My next step is going to be to see how practical it might be for people to have a goofy looking teosinte plant in their south facing window in their house to see if they can keep the aphids going that way.”

Stewart noted that Maryland researchers are trying to find plants that attract beneficials, such as buckwheat, cilantro, dill and alyssum, and plant them at different times of the year for continuous bloom, then monitoring how they encourage beneficial insects. Other research is looking at habitats and food sources that will keep parasitoids around nursery crops. Other growers at Farmer to Farmer said that cilantro, Gazania and Sweet Annie artemisia attracted aphids. One used to use Sweet Annie as a trap crop around peppers, peas and other susceptible crops.

Zuck mentioned that aphid midges (Aphilodetes) – the midges that make a cloud of bugs in the air on summer evenings while doing their mating dance – lay their eggs in aphids colonies and the larvae attack the aphids. They are available as ready-to-hatch pupae and are “your first line of defense” against an aphid infestation, with Aphidius following up.

Grower John Pino reminded Farmer to Farmer participants of his success with chickens. Since putting them in his greenhouses for a month in the winter before his seedlings go in, he has had good control of all insects into the summer, until he starts seeing cucumber beetles fly in. He doesn’t see any aphids until August.

Grower Mark Guzzi said that he now puts beneficial nematodes on everything he transplants to the field, mixing them in with the transplanting water. His problems with cutworms and root maggots have declined since using this prophylactic. He’s going to use Plantshield, a beneficial fungus that protects against soil-borne fungi, this year in the same way.

One grower brought up the lily leaf beetle, a recent pest in Maine. This bright orange beetle is smaller than most ladybugs and has a larva that looks like a slug. The insect can defoliate true lilies (not daylilies) and is more of a pest in the field than in greenhouses. Stewart said that neem oil works on the larvae and is supposed to repel the adults, but he’s not sure that works so well.

Resources

Abundant Life Seed Foundation, PO Box 772, Port Townsend WA 98368; $2 optional donation for catalog. www.abundantlifeseed.org/grains.htm

Gempler’s, Inc., PO Box 270, Belleville WI 53508; www.gemplers.com; scouting supplies

The Green Spot, Ltd., 93 Priest Rd., Nottingham NH 03290-6204; 603-942-8925; fax 603-942-8932; www.greenmethods.com and www.ShopGreenMethods.com.

Haverhills, 5575 W. 78th St., Edina MN 55439; 800-797-7367; www.haverhills.com

IPM Laboratories, Inc., Locke, New York 13092; 315-497-2063; fax 315-497-3129; [email protected]; www.ipmlabs.com.

Johnson, Warren T., and Howard H. Lyon, Insects that Feed on Trees and Shrubs, 2nd edition, Cornell University Press, 1988.

Sinclair, Wayne A., Warren T. Johnson and Howard H. Lyon, Diseases of Trees and Shrubs, Cornell University Press, 1987.

Stewart, Colin, Homeowner/Greenhouse IPM Specialist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension Office, 491 College Ave., Orono ME 04473; 866-7097; [email protected]; https://pmo.umext.maine.edu/greenhse/Grnhouse.htm

Zuck, Michael, Everlasting Farm, 2106 Essex St., Bangor ME 04401; 947-8836.