|

By Diane Schivera, M.A.T.

Deciding how to rotate pastures on your farm can be confusing! You have to consider many stable factors, such as soil type and slope of the land, and shifting factors, such as the amount of feed in the field at a given time and the weather.

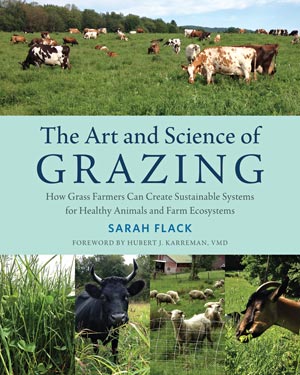

Many resources are available to help with these multiple decisions. Now Sarah Flack, a grazing consultant from Vermont, has written a comprehensive resource: “The Art and Science of Grazing – How Grass Farmers Can Create Sustainable Systems for Healthy Animals and Farm Ecosystems” (Chelsea Green, 2016). Flack took pasture management graduate studies at the University of Vermont and Holistic Management training. She has worked with farmers on their pasture systems for many years. This book is a culmination of that work.

Flack explains the benefits and systems of good grazing management. She tells how well-timed rotational grazing is key to everything, from thriving soil microorganisms to a healthy earth and everything in between. On the other hand, continuous grazing (leaving animals on a piece of ground for the pasture season) will not improve any part of the system. Animals must be moved to different paddocks as often as your labor force and plant growth allow.

Including “Science” in the title is apt, as Flack thoroughly and clearly explains how pasture plants grow in general, the growth patterns of specific plants, how plants adapt to different management and the importance of soil testing. The information about how different plant species grow is so useful when setting up rotations or deciding which plants you might want to seed into your pasture.

Flack also explains the physiology of ruminant animals, their dietary requirements, why they eat different plants and how they decide what to eat. She includes possible methods for preventing health issues that can develop on pasture and ways to judge how well fed your animals are.

She tells how to calculate how much your pastures are producing and how much acreage you need to support your herd or flock, and then she presents ways to design a rotation system that can work on your farm, taking into account its specific nature.

The “Art” in the title is reflected in descriptions of many individual farms and how they manage the idiosyncrasies of their operations, whether soil types, drainage, plant species or livestock requirements.

Following are some of the points I believe are important for grass farmers to emphasize.

A key benefit of grazing management using short grazing periods and recovery periods is that plants fully recover from being eaten, resulting in healthier soils with all the benefits of increased organic matter, including increased water-holding capacity – so important with today’s unpredictable climate. I see many poorly drained pastures that may be improved with ditching, subsoiling or drainage. Some, however, are so poorly drained that only sedges and/or rushes grow well. These wetlands are important to the ecology of the farm and the world, as they balance water flow and flooding. Often they are best fenced off permanently and only “flash grazed”(grazed for a very limited period just to manage some of the bigger growth) rather than being part of a rotation scheme on a farm.

The first thing to do on a new pasture is a soil test! This will provide information to assist and improve your management. Address pH first; other amendments and seeding should come second.

Well managed pastures – those with a high stock density per paddock, smaller paddocks and shorter grazing periods – result in evenly distributed manure. As the microbial community in the pastures develops, that manure will be broken down rapidly. This will eliminate the need to drag pastures, reducing your fuel bill and soil compaction.

Good spring growth of pastures is essential for the season’s production of the plants and animals. To have good spring growth, plants must not be grazed too short in the fall. This maintains plant crowns, new tillers and root reserves. Letting animals have the whole pasture late in the season “to clean up the pasture” often damages plants permanently by destroying their growing points, or damages them enough that they struggle to establish themselves in spring. This results in undesirable plants taking over.

Supplementation for animals – especially dairy animals – on pasture is very common. They must not be fed excess protein during the pasture season. Well managed pasture plants generally have more protein than the animals actually need. Supplementing with even more protein can upset animals’ metabolism, causing health issues. Also excess nitrogen on the fields from urine and manure can volatilize into the atmosphere.

Keeping animals on the same pasture for too long will damage the pasture because after three days (or longer if the regrowth is slower), grazed plants will begin to grow again. This new growth is like candy to grazing animals! They will search for these new shoots and will not eat the older, tougher growth. The overgrazed plants will have trouble surviving and will die if grazing is too severe.

Leaving plant material after animals have gone through the paddock is good. The goal is not to make the pasture look like a lawn. Leftover plant material is especially beneficial when animals trample it in densely stocked paddocks, because the plant material is broken down even faster by the pasture microbiome, increasing the organic matter level in the soil.

You can determine whether your ruminants have been getting enough to eat by – besides hearing them bellow when they are hungry! – knowing how to judge rumen fill. Check the triangular area below the short ribs in front of the hip and behind the ribs on the left side of the animal. If it is convex rather than concave, the animal’s rumen is full.

Planning is a great tool, but always do it in pencil; always be willing to revise plans to accommodate weather and other changes.

As MOFGA’s livestock specialist, I can’t help but talk about some additional resources available for grass farmers.

The Maine Grass Farmers Network (https://extension.umaine.edu/livestock/mgfn/), established 2004 with a USDA SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education) grant, presents a yearly conference the third Saturday in March. This year our keynote speaker will be Fred Provenza on grazing behavior. We also publish a seasonal newsletter and have a no-till drill and manure spreader (acquired from a Conservation Initiative Grant from NRCS) available for members.

The Northeast Pasture Consortium (https://grazingguide.net) is an alliance of graziers, extension and research personnel dedicated to improving pasture management in the northeastern United States. We share research findings, extension information, event announcements, photos and videos of interest to anyone involved with grazing livestock in our region and beyond.

On Pasture (https://onpasture.com) is a terrific weekly e-newsletter put together by Rachel Gilker and Kathy Voth. It has an amazing amount of material written by experienced farmers and grazing professionals.

Holistic Management International (https://holisticmanagement.org) is an organization that offers courses on grazing planning, farm goals, financial management and other topics. Its grazing planning charts can be a great foundation for recording your pasture rotations. I would be happy to help you use any of HMI’s information.

Diane Schivera is MOFGA’s organic livestock specialist. You can reach her at 568-4142 or [email protected].