By Roberta Bailey

Close to 2 acres of the Common Ground Country Fair’s permanent site is being planted to an experimental orchard. Another quarter acre or so will be a tree nursery. Both sites will be test plots for soil amendments, cover crops, rootstocks, and new and old fruit cultivars, hardy and tender. A portion of the orchard will be devoted to fruit cultivars that originated in Maine over the last 200 years or more.

As you visit these experimental plots and watch them grow over the years at the Fairgrounds, you may cultivate your own desire to start an orchard. Here are some tips.

Choosing a Site

Unless you are buying land, choosing your site is limited by the property that you already own or manage. The best sites for fruit crops have well-drained, deep, fertile soils; protection from wind; good air drainage; and full sun. A gentle slope with six to eight hours of full sun per day is ideal. Good air flow moderates frost and fungal diseases. Choose the site on your land that encompasses as many of these features as possible.

Avoid the temptation to plant less hardy varieties, especially early bloomers, on sunny south- or west-facing slopes. These sites tend to warm up before the danger of frost has passed. Trees may flower early, then suffer frost damage and lose the current fruit crop.

A standard apple tree needs 30 feet, a semi-dwarf needs 15 feet, and a dwarf needs 10 feet of space per tree.

Choosing a Tree

Apples do not grow true-to-type from seed. Virtually all apple trees sold are grafted: A small piece of the cultivar is grafted onto a rootstock. The fruit type is determined by what is grafted onto the rootstock, while the rootstock determines the size of the tree and how and when it will bear fruit. A mature tree on standard rootstock can reach 25 feet or more and bears fruit in about five years under ideal conditions. A semi-dwarf will grow to 70 to 80 percent of the size of a standard, bearing in three to four years, and a dwarf will grow 6 to 8 feet and bear in two to three years.

Rootstock also affects lifespan. A standard will live over 100 years. The old trees that we pick now are all standard trees. A semi-dwarf tree will live about 10 to 15 years; a dwarf, about 10 years. Dwarf trees usually need a trellis or support system. Many dwarf and semi-dwarf root systems are sensitive to cold, wet soils and drought. Some roots anchor better than others. Ask about rootstock when you order trees. You need a rootstock that will do well in your soil conditions. The Backyard Orchardist by Stella Otto covers rootstocks in detail.

Choosing a variety or cultivar can affect your success rate and the amount of maintenance needed to harvest clean fruit. Clean apples are difficult to raise without some sort of spray program. (Steve Page and Joe Smillie’s Orchard Almanac is an excellent book on month by month orchard maintenance.) Many old varieties will give you at least 50 percent blemish-free fruit with little care. Some of the newly developed varieties are resistant to scab and other diseases. If your supplier does not offer you good information, the library or internet can. Research your choices.

Preparing Your Site

A year or two of forethought and ground preparation can result in decades of successful fruit growing. If preparing an entire orchard site, consider planting a series of cover crops. Buckwheat followed by a fall crop of rye will smother weeds and increase organic matter. A low-growing clover can be established as a perennial cover crop in the orchard by sowing its seed with oats as a nursery crop. The oats get mowed before they go to seed, leaving a protective stubble for the young clover.

Mark Fulford, a soil consultant from Monroe, Maine, advises loading the soil before planting by spreading minerals and organic matter on the surface of the soil. The nutrients do not need to be tilled into the ground, he says. Just spread the nutrients, then mulch with wood chips. This method brings the soil to a ‘highly active condition,’ cultivating microorganisms that are best suited for trees and enhancing the ability of soil particles to attract minerals.

A wide range of minerals can be added. (A soil test from Cooperative Extension or from a soil consultant is highly recommended.) Azomite, the A to Z of Minerals and Trace Elements, applied at 300 to 600 pounds per acre or 10 pounds per tree is an ideal source of over 67 beneficial minerals. Granite dust, dolomitic or high calcium limestone, or greensand can be added at a rate of up to 15 pounds per tree. Aragonite, usually crushed oyster shell, is an excellent source of calcium in soils that are too high in magnesium. (Magnesium can tie up other nutrients in your soil.)

Once the needed minerals are broadcast, spread a wheelbarrow load of seaweed or compost around each tree site. Then dilute 1 cup of sugar or molasses in 3 gallons of water and pour or spray this evenly over the soil surface around each tree to feed the bacteria. Do not add manure. Then mulch the area thickly with wood chips, covering the entire mineralized area. The following spring, dig your hole and plant.

This feeding program also benefits established trees greatly. The minerals should be spread out to the drip line. On newly planted or young trees, make a circle at least 2 feet out from the tree trunk.

Planting Your Tree

Dig a large hole at least twice as wide and 6 inches deeper than the root system. A larger hole is more beneficial. We mix a quart of rock phosphate, azomite, and a few shovels of compost with the soil. Try to plant on an overcast day or late in the afternoon. Soak the tree in a bucket of water for a few hours before planting and don’t let it dry out while planting. Nestle your tree into the hole so that it will grow at the same height it was in the nursery. Spread the roots in the hole and don’t let them wrap around the hole. Refill the hole, making sure no air pockets form around the roots by gently tamping the soil. Build a bowl or rim at the top of your hole that will hold water and then thoroughly soak the soil. Apply at least 1 inch of water per week – via rain or irrigation – during the entire first year. Mulch with wood chips.

Keep a record. Label your tree with the varietal name on a metal tag; the plastic tags that come with your tree are temporary. Write the names in a book. Make a map. I’ve seen orchard maps painted on the inside wall of a barn.

Prune your new tree to a whip, removing all side branches and cutting the central leader to a healthy bud at 3 feet. This ensures that the root system gets established without the stress of trying to maintain a large branchy top. For pruning in future years, consult Cooperative Extension pamphlets or a good pruning book.

Tree Survival Tips

Apple trees in Maine have three main predators: rodents, deer and apple borers. Deer are a difficult problem. We protect our orchard with a young dog who stays outside all night. Our nursery is protected with an 8-foot high woven wire fence. Electric fencing works well, but needs more maintenance. Individual trees can be fenced. Highly scented soaps are a partial deterrent. Some of the deer repellent sprays do actually work, too.

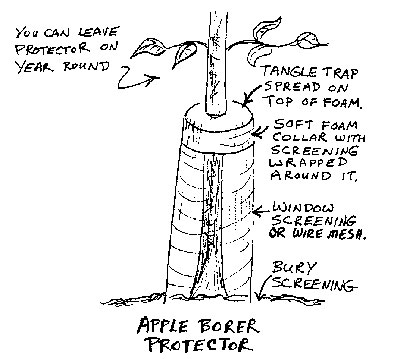

Fruit trees need protection from mice. A wire or screen collar or the commercial plastic collars offer good protection. They must be applied in the fall and removed in the spring. Apple borer guards double as mouse guards.

|

| Protect trees from apple borers by enclosing the base in window screening or wire mesh. Illustration by John Bunker. |

Roundheaded apple borers are one of the worst enemies of young apple trees. If you have ever had a tree that just stood there or even fell over, inspect the trunk within the first 18 inches above ground; you might see a small hole with rusty, chewed sawdust coming out of it – a borer hole. These insects chew and hollow the tree for up to three years. They can be dug out with a knife or killed by snaking a wire into the hole and piercing them. Even serious carving is less damaging than a borer.

Borers thrive in shady, moist environments and are most active in June and July. Keep tall grass away from tree trunks. Mulch is ideal for this. We have had great results with our homemade borer collars of 1/8-inch hardware cloth or metal screening wrapped around the tree trunk. It must be 1/8″ or smaller to exclude adult egg layers. Push the screening 2 to 3 inches down into the soil. Add a top collar of closed cell pipe insulation to prevent the adult borer from slipping beneath the mesh to lay its eggs, and smear Tangletrap on top of the collar to increase the deterrent. Be sure to loosen the screen as the tree grows. This guard can be left on year round, doubling as mouse protection in the winter.

For accurate information on what nutrients your trees are actually absorbing, you can pick live leaves in midsummer and bring them to Highmoor Farm for tissue analysis. Call Highmoor Farm for more information: 207-933-2100.

Watch the Fair site to see how the orchard progresses and keep listening for information on presentations on orcharding that will take place at the site.

Bibliography

Fedco Trees 1998 Planting Guide, John Bunker

Mark Fulford, soil consultant, Monroe, Maine

The Orchard Almanac, Steve Page and Joe Smillie, AgAccess, 1995 (The only remaining copies are available through Fedco Trees, PO Box 520, Waterville, ME 04903)

The Backyard Orchardist, Stella Otto, 1993, Ottographics