|

| These foxes are residents at Becky Weed’s Thirteen Mile Ranch in Belgrade, Montana. Photo courtesy of Becky Weed. |

By Tim King

Coyotes, fox, raccoons, hawks, owls and, in some places, wolves, cougars and bear can make strong farmers weep. Coons in the chicken coop or coyotes in the new lamb crop can bring tears to your eyes, then make you see red, then cause you to reach for a gun, trap or poison. It’s what farmers have always done, right? Maybe not.

A new breed of farmer is learning to live in harmony with predators. Whether livestock producers in the Himalayas in India, on the vast grasslands of Namibia, on the high plains of Montana, or near the north woods of Maine, predator friendly farmers share a similar idea. “We don’t want to kill them because it’s just as much their place as ours,” says Gloria Varney of Nezinscot Farm, a diversified organic dairy in Turner, Maine. “We need to learn to coexist, and what that means for us as farmers is we’ve got to get better at things like keeping the fence up.”

Knowing the Predators in Maine

One of Varney’s most predacious predators is a female fox. “She’s got to eat, too, but if you have good fence and good predator control, she’ll find that she’s not going to get an easy lunch here, and she’ll hunt somewhere else,” Varney explains.

Most farmers wouldn’t sympathetize with the needs of this fox. She destroyed 25 of Varney’s turkeys a few years ago, three weeks before Thanksgiving, after “the young man that was working for us threw a bale of hay into the paddock and he knocked the electric fence in,” says Varney. “That grounded the wire, and that’s the main source to my Flexinet that I use for the poultry. What’s frustrating about fox is she just keeps killing and pulls them out and tucks them somewhere and then goes and gets another one. She tucks them under bushes so she can bury them later on.”

|

| A guard llama protects sheep at Thirteen Mile Ranch in Montana. Photo courtesy of Becky Weed. |

Part of being a successful, predator friendly rancher or farmer is understanding your neighborhood predators. Varney knows what the local fox does with its prey. She also knows her daily hunting routines and her den location. “She comes at dawn, just before the sun comes up,” notes Varney. “That’s usually when we’re working outdoors. The commotion with us being there deters her.”

Human noise keeps the dawn hunting fox away from the area where humans are working, and Nezinscot Farm’s noisy and aggressive llamas, alpacas and donkeys, which are often with the farm’s sheep, keep the fox from going to that part of the farm.

“She has to come through the pasture, but she’s figured out how to keep on the perimeter and keep away from the donkeys and llamas. With the donkeys I can tell when the predators are around, because they start bellering,” Varney says.

Varney has had some problem with coyotes, but she’s learned to work around them. They travel through her riverside farm along a set route. “It kind of bypasses my back pasture and heads down through my front pasture,” she says. “You can’t disrupt their pattern; it’s been there longer than we have. But the coyotes are predictable and kind of scared of you.”

Varney doesn’t mind if a predator has a snack on the farm. In fact the farm has a regular spot in the woods where animals that die are placed, and predators know that an occasional sanctioned meal of livestock can be found there.

|

| The Predator Friendly logo is available for predator friendly farmers to use on their products. |

Predator Friendly Certification

Nezinscot Farm’s electric fences and Flexinet, guard animals, and understanding of predator behavior have allowed the farmers not to kill predators. When Varney heard about the Predator Friendly certification program, based in Montana, she thought it might help market the yarn made from her sheep’s fleeces as well as the farm’s organic beef, veal, lamb, turkey and chicken, all sold at the farm’s store.

The nonprofit Keystone Conservation, based in Bozeman, Montana, promotes and administers the national Predator Friendly certification program. Janelle Holden, the Keystone Conservation staff person who oversees the program, says that getting a Predator Friendly Label approved by the USDA for use on meat products would be a long and expensive process similar to that involved with getting the Certified Organic label on meat products. The organization is currently promoting the concept of Predator Friendly livestock production to farmers and ranchers. A common label has not been developed yet.

The Predator Friendly certification concept was developed originally by Montana sheep rancher Dude Tyler and conservationist Lill Erickson early in the last decade. They organized a group of people, including a predator biologist, a clothing designer and a couple of ranchers, to work out how a third party certified predator friendly label might work. In the process they created Predator Friendly, Incorporated. In 2003 Keystone Conservation took over the certification program.

|

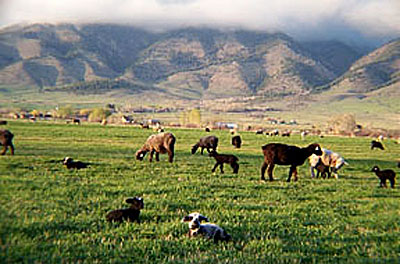

| Lambs in this pasture are close to Becky Weed’s house, which offers some protection from predators by its proximity. Photo courtesy of Becky Weed. |

Living with the Locals in Montana

“The main point of the Predator Friendly standards is you make a written commitment not to shoot, trap, poison or kill native species like coyotes, bears, mountain lions, eagles in order to protect your flock,” explains Becky Weed, a sheep rancher from Belgrade, Montana.

Weed, whose Thirteen Mile Ranch was one of the very early ranches to be certified, has a philosophy similar to Varney’s. “Our guard llamas have developed some kind of an understanding with a local population of a fairly stable coyote pack,” Weed says. “They know the ropes and we know the ropes, and I think they understand that we don’t bother them. We see them frequently. We like to have them around, because they hunt gophers.”

Thirteen Mile Ranch’s ewes lamb on pasture, which would seem to add risk, but that risk is minimized by having lambing occur in a pasture close enough to home that Weed can look out the window and see the lambs. They’ve had no problem with coyotes in the lambing paddock.

Weed’s personal experience with her local coyotes jives with research conclusions of predator biologist Bob Crabtree, one of the founders of the certification program.

Crabtree studied coyotes in the Yellowstone area and in Washington state a few years ago. He concluded that shooting a coyote gives a shepherd only brief reprieve. Before long, he claims, another one replaces the marauding coyote.

|

| A scenic view of content, protected livestock. Photo courtesy of Becky Weed. |

“It sounds counter-intuitive, you know, if you kill adult coyotes that you’re not alleviating the problem. But the problem is, coyotes are social, and they pass this right on to other members of the pack, and often the next night there’s another coyote to take its place. So there’s immigration into the area, and there’s immediate filling in the vacancy. So you’d think that if you kill a bunch of coyotes that there’s going to be fewer, and less lambs are going to be killed, but that’s not the case,” Crabtree told the radio program Living on Earth.

Plenty of people disagree, but Weed’s experience is that at least her trained coyotes fit the research model. They’re not bothering the sheep, and they’re keeping sheep-eating coyotes out of the area.

Mountain lions are different, according to Weed. No resident lions in the Valley have been trained, and a lion may not take training lessons from a llama.

“Last fall we had a lion problem,” Weed says. “That lasted about six weeks or so. Because we’re in a four-year drought, the deer and elk come out of the mountains looking for feed, and the predators follow. We lost eight sheep last fall. That was a significant loss.”

Under Predator Friendly certification, Thirteen Mile Ranch could have gone after that lion and killed it. Weed would have lost her certification for the year but could have reapplied the following season. Instead, she chose to show the lion it wasn’t worth eating sheep instead of deer and elk.

“Part of the problem was that we were away in the beginning, and then, before we realized what was going on, we lost the sheep,” Becky says. “We debated about getting guard dogs, but in the meantime we sometimes sleep out in the back. We’ll take walks at unpredictable hours during the night, and we have a really powerful flashlight we’ll shine around. We just do a lot of unpredictable things. We move our sheep around to different pastures, for instance. Once we started doing that we stopped having trouble. It didn’t stop right away. It was sort of incremental. Every time we have an episode like this, we feel we learn more about the predator’s behavior and learn what to do to keep it off balance.”

Weed never saw that lion. So, she figures, she wouldn’t have had an opportunity to shoot it even if she had wanted to. Instead she matched her shepherd’s guerrilla tactics with the lion’s guerrilla tactics and, apparently, won.

Weed uses her Predator Friendly certification to promote the meat and wool products she and her husband direct market from Thirteen Mile Ranch.

“The reason eco-labels work,” says Janelle Holden of Keystone Conservation, “is that they give producers a way to tell their story. People won’t necessarily buy a product just because it’s predator friendly, but it does make someone unique enough to highlight their product in the market.”

|

| Pakistani farmers make corrals to protect their livestock from endangered snow leopards. Photo courtesy of Rodney Jackson of the Snow Leopard Conservancy. |

Saving Endangered Species Abroad

Predator friendly farming and ranching isn’t just a marketing scheme, however. It does protect predators from the ravages of conventional agriculture. That is perhaps most telling in settings where endangered species are involved. Rodney Jackson works with the Snow Leopard Conservancy in the Himalayas in Ladkh, India, and in Pakistan. His work has revolved around such simple things as improving corrals for night-time confinement.

“We have predator-proofed corrals in more than six communities. No loss of livestock has since occurred from these livestock pens. For each set of improved corrals, we estimate that up to five snow leopards are removed from the threat of retributive killing,” Jackson writes in an email.

In southern Africa, and especially Namibia, the Cheetah Conservation Fund has worked for years with farmers to establish predator friendly livestock management. Laurie Marker, the organization’s executive director, says that cheetahs and leopards prefer wild game to cattle.

“Here in Namibia we have a mixed and integrated farming system – all our cattle farms have free-ranging game on them,” Marker writes in an email. “And, instead of having game-fenced farms, many of our good, conservation minded farmers are members of what is known as Conservancies. Conservancies practice this integrated and mixed livestock and wildlife management and also are able to manage their farms with predators a part of the system, as they also practice sustainable use – therefore, maintaining a high enough prey base of wild, free-ranging game, so that their livestock is not in as much threat [from] predators. We have found here in Namibia that the game farmers have removed or killed more cheetahs than the livestock farmers – as they want the game only for themselves and they do not want to share it with the predators.”

The purpose of a certification program, whether in Maine or Namibia, is to allow farmers who want to pursue these practices to connect with consumers who care enough so that they will reward the farmers for their predator friendly farming practices.

For more information about predator friendly farming certification, contact Keystone Conservation, P.O. Box 6733, Bozeman, MT 59771; 406-587-3389 (ph); 406-587-3178 (fax); [email protected]; www.keystoneconservation.us

Other contacts:

Nezinscot Farm, 284 Turner Center Rd., Turner ME 04282; 207-225-3231

Thirteen Mile Ranch, 13000 Springhill Road, Belgrade, Montana 59714; Tel. (406) 388-4945; www.lambandwool.com

Laurie Marker, Ph.D., Executive Director, Cheetah Conservation Fund, P.O. Box 1755, Otjiwarongo, Namibia; (264) 67 306225; www.cheetah.org

Rod Jackson, Snow Leopard Conservancy, 236 North Santa Cruz Ave., Suite 201, Los Gatos, CA 95030; (408) 354-6459

About the author: Tim King and his wife, Jan, farm in Long Prairie, Minnesota. Tim wrote about his farm in the June-August 2004 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.