|

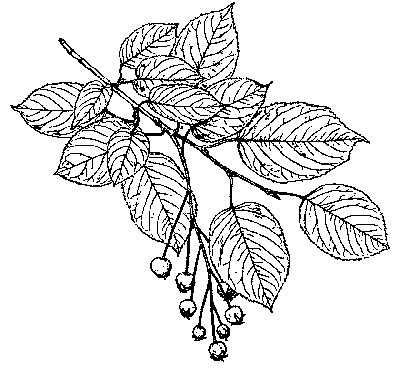

| Smooth Northern Shadbush. Amelanchier laevis. |

While traveling through Ontario last summer, my partner and I stopped at Niagara Falls and then the Whirlpool Rapids. Neither of us is fond of crowds or tourist traps, but the energy of all that water inspired an awe that made our tourist status worthwhile. Seeking a quieter picnic spot, we stopped at Whirlpool Rapids. Next to the parking lot was a large stand of Juneberry trees, laden beyond belief with ripe fruit. Late June, sun on our shoulders, we picked and ate juneberries until full, then picked and ate some more, and the memory of that picnic remains far more vivid than that of all the water.

What are Juneberries?

Juneberries, serviceberries, saskatoons, shadberries, or shadblow (Amelanchier species) are multi-stemmed trees or large shrubs ranging from 8 to 18 feet, depending on the species and variety. Extremely hardy (zone 2), they range as far north as Alaska. They are the first trees to bloom in the Maine or New England countryside, a week or two earlier than the pin cherries. Cultivated varieties can be quite ornate, with showy masses of white blooms. Fall foliage can be striking red, orange and gold. They bear fruit in late June or early July.

The fruit is similar to a cranberry in size, but soft and; red to dark purple when ripe. Its flavor is mild and sweet, sometimes compared to a blueberry, though that thought has never come to my mind. The fruit was a mainstay in the Western native diet, used fresh, then dried and mixed with venison or wild game to make pemmican. Later it sustained settlers on the Western prairies. Today the fruit is enjoyed fresh, canned, frozen, or dried like raisins. They are baked in pies and made into preserves and wine.

Juneberries are slightly higher in vitamin C when picked underripe. Fully ripe fruit has a higher sugar content, which is best for fresh eating and wine making. Juneberries prefer soils with a pH between 5.0 and 7.0. They thrive in a wide range of soil types, even tolerating wet areas, but not standing water. An understory species in the wild, they will grow in full sun to partial shade. They don’t need extremely rich soil; average soil will do.

Propagation and growing

Planting the trees

The berries are propagated from seed, cuttings, or rooted suckera that spring up around the plant. When buying a bare-rooted plant, choose one with a well developed root system. Take care not to injure the roots, and keep them damp and avoid even minimal exposure to sunlight.

Most varieties of Juneberries are self-fruitful, but to ensure optimal pollination, plant more than one variety. Space plants 8 feet apart for short varieties and 12 feet for taller ones. A 6-foot spacing will create an attractive hedgerow.

Dig a bushel basket-sized hole, mixing some compost with the topsoil. Next, Ppant the bush at its original depth, visible by the soil line on the bark. Then, fill in the hole around the roots, gently tamping out air holes. If the soil is very dry, water in the plant a few times as you fill in the hole.

Tree care and pruning

Mulch around the tree, eliminating the need for further cultivation. If you do have to weed later, cultivate shallowly to avoid damaging surface feeder roots. Water your young tree every week until fall.

Pruning juneberries is simple. Once plants have plenty of branches, prune in spring before growth starts and after danger of severe cold weather has passed. The best fruit is produced on second year wood, and some fruit is produced on older wood. If a shrub needs to be thinned or envigorated, remove older branches. Some people head their shrubs at 6 feet for easy picking. Remove any low branches as well. Plants start to bear in two to four years.

Plant breeders work with the wild serviceberry or shadberry to create many larger fruited, more shrub-like varieties. Recommended varieties include ‘Honeywood’ (6’ to 8′), which is full flavored, later ripening and ripens over a long period; ‘Thiessen,’ with large fruits and an open shape; ‘Smoky’ (6′ to 8′), a mild fruited, vigorous bush; ‘Regent’ (4′ to 6′), a vigorous plant with quality fruit and the most ornamental flowers and fall color; and ‘Pembina,’ the tallest variety (8′ to 15′), selected for heavy fruit yields.

Types of Juneberries

“Amelanchier taxonomy is fraught with difficulty and certainly not clear-cut,” says Michael Dirr in The Interactive Manual of Woody Landscape Plants. (PlantAmerica, Inc., Arlington, Virginia, 2001). “It is reasonably fair to state that what one orders and receives is not necessarily the same in the world of serviceberries. Although many nursery catalogs list A. Canadensis, in fact, what is sold is A. arborea, A. x grandiflora, and A. laevis.” He lists the following species:

A. arborea

Downy serviceberry, juneberry, shadbush, servicetree, sarvis-tree – a 15- to 25-foot-tall, multi-stemmed shrub or small tree, hardy to zone 4. Many introductions exist. Native from Maine to Iowa, northern Florida and Louisiana.

A. alnifolia

Also known as the Saskatoon serviceberry – developed for commercial fruit production; closely allied to A. florida (now A. alnifolia var. semi-integrifolia) and much confused with that species, but A. alnifolia has smaller flowers, thicker, rounder leaves, and is smaller in habit. Hardy to zone 4.

A. alnifolia var. semi-integrifolia

Also known as the Pacific serviceberry – an erect shrub or small tree to 10 feet tall or taller; native from southern Alaska to Idaho and northern California. Hardy to zone 2.

A. canadensis

Also known as the shadblow serviceberry, thicket serviceberry – “often confused with A. arborea and, in fact, the two are used interchangeably in the nursery trade.” An understory shrub with erect stems, spreading by suckers, in bogs and swamps from Maine to S. Carolina along the coast, hardy to zone 3. Flowers about one week after A. arborea.

A. x grandiflora

Commonly known as the apple serviceberry – a hybrid between A. arborea x A. laevis. Hardy to zone 4.

A. laevis

Commonly known as the Allegheny serviceberry – closely allied to A. arborea but with bronzy new leaves that are not pubescent. Black, sweet fruits were preferred by Native Americans. Native from Newfoundland to Georgia and Alabama, to Michigan and Kansas; hardy to zone 4.

A. stolonifera

Also known as the Running serviceberry – 4- to 6-foot-tall shrub that grows erect in thickets. Native from Newfoundland to Virginia; hardy to zone 4.

Other small, suckering species that are not common in commercial horticulture are A. humilis, A. obovalis, A. spicata and A. bartramiana.

Bibliography

Bart Hall-Beyer and Jean Richard, Ecological Fruit Production in the North, published by Jean Richard, 1983.

Fedco Trees 2001 Catalog, (P.O. Box 520, Waterville ME 04903).

St. Lawrence Nursery 2001 Catalog (325 State Highway #345, Potsdam NY 13676).

Stanley Schuler, Gardens Are for Eating, Collier Books, 1975.

Roberta Bailey is a long-time regular contributor for MOF&G.