|

| Japanese knotweed or Japanese bamboo is not a true bamboo. Eliminating it takes diligence – cutting it back frequently during the growing season and then mulching heavily. English photo. |

|

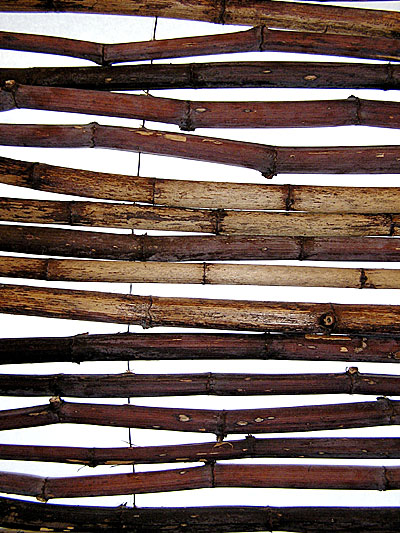

| A window covering made by Cleveland artist Eric Vanyo from Japanese knotweed stalks. English photo. |

|

| Close-up of the bamboo window covering. English photo. |

By Bruce Blake

The landscape of Maine has been altered almost beyond recognition over the last 400 years. I don’t want to suggest that this land was some sort of Rousseau-like paradise before Europeans arrived or that change is inherently negative, but the land has been enormously changed by human activity. Among the most significant alterations has been the arrival of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of exotic species. While many of these introduced species have had minimal impact, some have produced substantial and undesirable consequences.

In a time when one-third of the remaining native North American bird species are listed as endangered, threatened or in serious decline and when over 300 of Maine’s native plants are now rare or worse, we can no longer be cavalier about conditions we can change.

Among the culprits are introduced exotic plant species. These can significantly disrupt ecological balance by crowding out native species, sometimes creating areas of monoculture where little other than a single exotic species survives. The displaced native species have evolved over millennia in the context of their environment and usually provide a superior source of food and/or habitat relative to exotic species.

Not all exotic species are inherently bad. That notion greatly oversimplifies some very complex issues. But some of Maine’s most common invasive exotic plant species have proven very problematic and are addressed here; sources listed at the end of this article lead to additional information.

Perhaps the most prevalent of Maine’s invasive species is Rosa multiflora, the Japanese, rambler or multiflora rose. Introduced as an ornamental and escaped from cultivation during the late 19th century, it is now found in every county in Maine.

This species can be quite difficult to eliminate. Small plants will be killed if they are kept mowed close to the ground for two consecutive years, but this requires at least monthly mowing from May through October. Plants can also be dug or pulled with a Weed Wrench (see Resources). You will probably need to cut larger plants back with loppers to get close enough to the base to dig or pull them. In areas with large infestations, often the easiest solution is to strip out the plants with a skid loader or bulldozer and then cover the area with a barrier layer to prevent reinfestation. Cardboard or a thick layer (six to nine sheets) of newspaper covered with several inches of mulch, wood chips or sawdust is usually adequate, but the barrier needs to remain intact for at least two full growing seasons.

Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and common barberry (B. vulgaris) are both found throughout Maine, as is a hybrid of the two, Berberis x ottawaensis. Barberry mutates readily, so dozens of cultivars exist. The red- or purple-leaved selections are probably the most familiar, but green-, yellow- and variegated-leafed forms also exist. Some selections are less prone to producing viable seed, but none of the common forms is 100 percent sterile.

This is another plant that should be dug or pulled with a Weed Wrench. The very fine thorns often work their way through even leather gloves, so use caution. Cut the shrub back with long-handled loppers to allow easier access to the base. Barberry may sprout again from root fragments or dormant seeds, so watch the area after removal and either hoe or apply a barrier layer if sprouts appear.

Many imported honeysuckle species are quite invasive. Tatarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica) is common in Maine. It was introduced to North American in the 18th century from Russia and Central Asia and has been widely used in New England as a robust and cold-tolerant shrub. Morrow honeysuckle (L. morrowii) is another invasive, large shrubby form that is fairly common and can hybridize with L. tatarica.

Although they grow into large shrubs, honeysuckles tend to be relatively shallow rooted, and even large specimens can often be pulled relatively easily with draft animals, a tractor or pickup. They can also be dug by hand or pulled with a Weed Wrench. Root fragments will often sprout again, so you may need to watch the area for several years. With large infestations, a controlled burn during the growing season is often the most efficient eradication method, but it may need to be repeated several times, often over two consecutive years.

The vining Japanese honeysuckle (L. japonica) is perhaps an even greater threat to Maine’s native plants. Like many vines it grows rapidly and is quite aggressive. It seems to particularly favor habitats along streams or woodland edges. Fortunately, L. japonica also tends to be shallow-rooted and can be hoed, dug or pulled with the usual caution to watch for sprouting.

Several less common invasive exotic honeysuckle varieties exist, while desirable native honeysuckles, such as the vining trumpet honeysuckle (L. sempervirens), are not invasive. If you have doubts about identification, seek assistance.

Asiatic bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculata) is another highly aggressive, exotic woody vine, but like honeysuckle it has a native cousin: C. scandens, American bittersweet. While our native species is also quite aggressive, it is not invasive in the sense that the Asiatic species is. Both can kill trees or shrubs that they are climbing, so even the native species may be undesirable in some contexts, but the native species can provide a valuable winter food for grouse, turkeys, songbirds, rabbits, squirrels and even fox. American bittersweet leaves are pointed at the tip, while those of Asiatic bittersweet are rounded at the tip.

This is another plant that is difficult to remove completely in a single season. Asiatic bittersweet produces seed prolifically, and people removing plants with a shovel or Weed Wrench will likely disturb the soil enough to permit some dormant seeds to germinate. The soil probably contains a substantial seed bank, so watch for seedlings. A temporary barrier of cardboard or newspaper and mulch will inhibit new growth, but if the soil is disturbed after the barrier breaks down, expect new seedlings to sprout.

|

| Burning bush is sold in some nurseries for its red fall color and for its interesting bark, highlighted in winter. It is, however, spreading in some forests in the Northeast and becoming invasive in places. English photo. |

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica, a.k.a. Polygonum cuspidatum) is familiar to most people in Maine as “bamboo,” although it isn’t related to true bamboo species. This plant is a nightmare to eliminate once established. It will sprout from even tiny root fragments, so attempts to dig it or pull it out are not recommended. The best organic control method is to cut it to the ground numerous times during the growing season; this will weaken it eventually, but requires a long-term war of attrition. If you have cut it to the ground every month to six weeks for a couple of years, it may be sufficiently weakened that a thick cardboard and mulch barrier may be adequate to finally kill it – but watch for new sprouts around the edges.

Black swallowwort (Cynanchum louiseae) is established in coastal Maine at least as far north as Lincoln County. The largest infestation I have seen is along the shore in Cape Elizabeth. This herbaceous perennial vine can be quite difficult to eradicate. Digging out the entire crown should kill the plant, but this is another species that produces huge amounts of seed, some of which will likely germinate after the soil is disturbed. Cutting the vine to the ground multiple times per growing season followed in subsequent years by cardboard or newspaper and mulch may eliminate it, but gardeners will likely have to battle the plant for several years.

Other terrestrial plant species that may occur in Maine as invasive exotics include Eleagnus umbellata, autumn olive; E. angustifolia, Russian olive; Acer platanoides, Norway maple; Rhamnus frangula, a.k.a. Frangula alnus, glossy buckthorn; R. cathartica, common buckthorn; Euonymus alatus, winged euonymus or burning bush; Alliaria petiolata, garlic mustard; Lythrum salicaria, purple loosestrife; Aegopodium podagraria, bishop’s weed; Tussilago farfara, coltsfoot; and Phragmites australis, common reed. Pyrus calleryana, the ornamental pear, also seems to be emerging as an invasive threat.

In addition to clearing invasive exotics from your own property, ask local land trusts and conservation organizations if they need volunteers for this job – if you have the time. The work is substantial, but the rewards inherent in restoring a bit of native Maine for future generations are worthwhile.

Resources

“Invasive Plants Threaten Maine’s Natural Treasures,” University of Maine Cooperative Extension Bulletin #2536; www.umext.maine.edu/onlinepubs/htmpubs/2536.htm

“Invasive Plants,” Maine Natural Areas Program; www.maine.gov/doc/nrimc/mnap/features/invasives.htm

“Controlling Invasives,” Native Plant Trust; https://www.nativeplanttrust.org/conservation/invasive/

Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health; www.invasive.org/index.cfm

USDA National Invasive Species Information Center; www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/index.shtml

I also recommended Douglas W. Tallamy’s book Bringing Nature Home, although I believe that he overstates the case for natives-only landscaping.

I have referred to using a Weed Wrench to remove woody plants. Several commercial variations on this tool exist, but I have the most experience using the original tool sold under that name. A well-regarded competing product with a larger base is the Extractigator from www.extractigator.com.

About the author: Bruce Blake is a landscape designer and horticultural consultant. His interests include gardening for wildlife and ecologically driven design, Japanese gardens, fruit trees and a broad range of other design, ecology and horticultural niches. He can be contacted through his website: www.blakegarden.com.