|

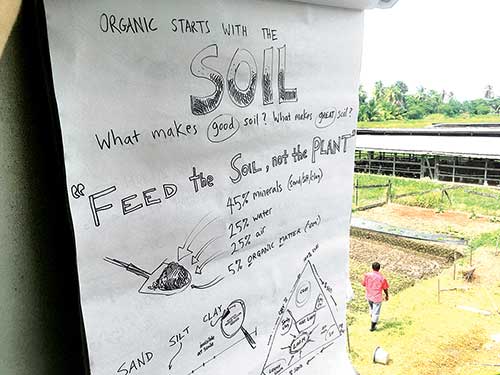

| The author conducted trainings on organic farming on various farms using on-hand demonstrations and flip-chart illustrations. |

|

| A Rastafarian farmer gives a tour of his diverse production area. |

By John Bliss

What does it take to build a movement? At what point does despair transform into hope; stagnation into motivation? How is a movement embodied in leadership, in community and in the landscape?

In November 2019 I had an opportunity to travel to South America with a U. S. Agency for International Development (USAID) project. I have written in The MOF&G in the past about the USAID Farmer to Farmer program (not to be confused with MOFGA’s Farmer to Farmer Conference) that recruits volunteers with specific expertise to share knowledge with farming communities throughout the world. This time I was sent to Guyana, which lies on the coast of the Caribbean Sea between Venezuela and Suriname.

Although these aid programs usually have conventional goals such as “cold-chain development” (temperature-controlled storage and transportation) or “finance for cooperatives,” this time I was to conduct short introductory trainings on small-scale organic vegetable farming. This was very exciting for me since it felt solidly in my wheelhouse, having been farming organically for 18 years as well as doing inspections for MOFGA Certification Services for the past three seasons.

Learning About Guyana

Preparing for a volunteer assignment in a place you have never visited is difficult. The climate, the culture, the markets as well as the expectations placed on you are mostly unknown. But diving in and being flexible make the experience a bit of an adventure. Learning about a part of the world and meeting interesting people is the reward.

In short order I learned that Guyana is a small country in population with a vast and sparsely populated rainforest ecology extending away from the coast. Along the sea the landscape is flat and fertile, although heavily exploited and abused throughout a long colonial history. Agriculture is still oriented toward sugar plantations and large-scale rice farming, but it is no longer competitive in global markets, so deindustrialization or underdevelopment has proceeded painfully for decades. Partners of the Americas, the NGO that implements Farmer to Farmer in Guyana, is at the forefront of educating communities in self-sufficiency and small-scale farming.

I met Jermaine during a heavy downpour on my first morning in Georgetown, the capital city. He is the program manager for Partners of the Americas and was my guide, my driver and my patient culture decoder for the duration of the assignment.

Guyana is a Caribbean country, sharing the heritage of Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and other “West Indies” countries. Driving the coastal highway revealed a landscape as clear as any history textbook of the colonial project. Dutch-engineered dikes divide the land with alternating irrigation and drainage canals. British measuring systems rationalize ownership in chains, rods and acres. The naming of places may not be particular to colonialism, but the British who took control of the coastal plain echo get-rich quick schemes from the early 19th century: “Good Intent,” “Three Friends,” “Maria’s Delight” and “Land of Plenty.” One might get the impression of lake-house camps or suburban developments, but these are plantation names with brutal histories where wealth was extracted only by the ubiquitous oppression of black slaves. A plantation called “Bachelor’s Adventure” earned its place in history after a huge slave rebellion in 1823 was quashed, with hundreds killed. The legacy of slavery, land exploitation and colonial resource extraction is obvious at every turn. After emancipation by the British in the 1830s, slaves were replaced by indentured workers from other parts of the British Empire, often working in comparably harsh conditions. Easily the most ethnically diverse country I have ever visited, people of Indian, West African, Chinese, European and Amerindian extraction live a narrative of resilience to historical trauma.

A Permaculture WhatsApp Group

During my first week, Partners of the Americas introduced me to a group that had organized around an online listserv on social media – the Permaculture-Sahakari WhatsApp Group. Its goal was to learn about and apply organic and permaculture techniques to members’ backyard plots and small farms not far from Georgetown. They had regular meetups and workshops, but the main function of the group clearly was encouraging and advocating for each other’s projects.

This was my first window in on movement building. The group started small, and the core members shared a desire to eat healthily. Seeing no organic food options at the markets, they resolved to educate themselves about growing their own food. Their motivations were varied and layered, but one theme I heard from several people was sickness – either of family members or of themselves. It is easy to forget that fundamental to change is suffering, and although we all suffer some hardships, acute illness can induce lifelong purpose. Here was a small group of educated people, well-off in society, who had been touched by pain. Either on advice from doctors, the internet or intuition, all had come to the not-unlikely conclusion that conventional food was central to their health problems, and their solutions had a feel of desperation, as we all experience when there is a glimmer of far-off hope.

I wanted to sit with this awareness and absorb it as much as I could, but there was a depth of feeling in their personal narratives that I did not need to probe. I saw that the social media platform was performing an emotional need, reinforcing commitment and persistence. These members often did not have the support of their family or neighbors, so without the WhatsApp group, their struggle would be lonely.

I toured their growing areas, some big, some small, some a decade old and others still dense with jungle vegetation. After most of a week of informal and structured conversation, I conducted a training day, based on the fundamentals of organic farming as I know it, and on research I had been gathering over the previous month. First and foremost, I shared the fundamental principles of organic farming, which I took from a training manual from the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM, which publishes loads of documents on organic farming and organizing):

The principle of health

The principle of ecology

The principle of fairness

The principle of care

Although focusing on these concepts took time away from the practical concerns of organic farming, I found that the discussion of principles revealed some important misconceptions. What makes organic farming different from simply farming without synthetic chemicals? Isn’t an Amerindian farmer (the term for those indigenous people living mostly in the interior of the country, in the rainforest) an organic farmer? Here I found it helpful to situate organic farming as a response to industrialism, and thus as part of a family of social and political movements stretching back in history.

We also discussed multiculturalism, often overlooked by even well-established organic advocates. Within the principle of fairness is acknowledgement and respect of the diverse cultural traditions that have inspired organic farmers. Especially as advocates of permaculture, which has folded so many indigenous techniques into its brand, the wider struggles of social justice should be embraced. Far from being an academic diversion, these conversations laid groundwork for movement building.

Production in this group was, in most cases, minimal, but all participants were openly sharing what they had. I was added to the WhatsApp group, and soon notifications on my phone were dinging every few minutes. The group shared ideas about leafcutter ant defense (as opposed to a pesticide bait), described trials and tests, and freely gave seeds and seedlings to one another. I was shocked by how networked this group was! If one member posted a picture of a vine full of butternut squash, that member was inundated by offers to buy two or three. Here was a waiting market, but without much in the way of product.

Organic Production Farms and a Participatory Guarantee System

As far as the Farmer to Farmer program goes, spending time with a community of affluence in the capital city was unusual. During my second week Jermaine and I traveled southeast along the coast into the farming villages more in line with my past experiences in East and southern Africa. Each day we toured production farms and met with a different group of farmers. I had two or three hours to offer an overview of the techniques of organic growing and led a discussion on organizing growers around a standard that could be leveraged in the marketplace. These farmers were already self-selected to have an interest in farming without synthetic chemicals, and previous trainings had covered concepts of composting and nutrient cycling, for example. But all were frustrated that the marketplace did not support a transition to all-organic production, given the higher costs they experienced by not using synthetic chemical fertilizers.

These conversations mirror those we have in our own communities in Maine. My farming colleagues have invested tremendous effort in developing Community Supported Agriculture enterprises, farmers’ markets and farm-to-restaurant relationships, all while driving the organic standard marketing message forward. Likewise Cooperative Extension, MOFGA’s farmer services and various other nonprofits participate directly in training and networking. Although the imperialist muscle of USAID is at the fore of my awareness, I do not see Partners of the Americas as implicated in that brand of influence or covert “consensus” building. Doing so would be turning a blind eye to quotidian global poverty of farmers like ourselves. But movement building is ideological by nature, and being honest about this is crucial to our effort.

One farmer in particular raised my awareness in this regard. His place was along a canal where he was alley cropping with beds of annuals between diverse tree crops. Working alone he had created a beautiful 2- or 3-acre market garden, striving to eschew conventional methods. A member of the Rastafarian community, he was on his guard as we came to visit his farm. A small delegation of municipal and state employees accompanied Jermaine and me. With open frustration, he vented about the politics governing the use of canal irrigation water for his crops. Rastafarians in Guyana are a significant religious minority whose black-nationalist roots can set up barriers between them and non-Rasta community members. The dispute over irrigation water as well as other frustrations in the local market seemed to be based on prejudice. While his religious and cultural identity had strongly fortified his independence from synthetic chemical inputs, it also jeopardized his integration in a community of producers (through irrigation rights). The local market also required close cooperation, and here I thought I could offer some insight.

Organic or close-to-organic production was indeed happening in these farming regions of the country, but no marketing strategies were communicating and guaranteeing its importance. As MOFGA Certification Services knows, being an accredited third-party certifier of organic products is a complex and expensive process. Exporting globally increases this complexity and is viable only where lucrative markets express a demand. Throughout my assignment in Guyana, a sense of priority emerged that, while export production may exist in the future, the near-term goal was to build an organic movement domestically. A Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) is a quality assurance system designed to function cooperatively, as in a peer-to-peer network. IFOAM again came to my assistance in articulating these ideas to the various stakeholders with whom I was networking. Many regions worldwide depend on a PGS to bring trust and security to markets, and their development has charted a decidedly nonhierarchical path. Here was another example of “organic” as a broad historical movement in the tradition of democratic grassroots activism.

Avoiding a top-down regulatory agency does not make a Guyanese organic movement easier. It places responsibility on individuals in the community to agree upon a standard and regulate each other. A PGS has structural aspects designed to accentuate democratic power, facilitate transparency and yet enable profit. My new friends from the Permaculture WhatsApp group were well-positioned to explore PGS development and create secure markets for producers. Farmers would still need plenty of technical assistance to achieve organic standards, but the networks were all but inevitable.

By the third week of my stay in Guyana, I had witnessed the potential of the movement: consumers searching for product, farmers considering new markets and activists willing to do the heavy lift of organizing. The single biggest obstacle to success was trust. The hungry consumers in the city did not trust the rural farmers to be honest about their production. The rural producers did not trust the urbanites to be loyal over the course of a growing season. Class issues were at the heart of this breakdown. This was my outsider perspective of course. Although I could say the same thing of the challenges in markets in Maine, I would instinctively inject all sorts of nuance into the assessment. Still, classism is the most helpful umbrella concept with which we can move forward progressively. On one hand, discrimination of all kinds can be addressed through regulatory means: building or dismantling justice standards through the state. On the other, as many farmers know, there is a natural beauty in a farmers’ market where conversations and familiarity can erode divisions.

A Participatory Guarantee System brings these two approaches together: An organized group decides its own rules and creates a protective market space. A peer-certification network achieves compliance and elevates everyone’s level of education around production.

Through this volunteer work in Guyana, my understanding of geography, culture and history grew – and I gained a deeper understanding of social justice movements globally. The work has allowed me to look more clearly at our own organic farming community in Maine, where we have been and where we need to go. MOFGA started with a PGS mentality, providing for the needs of its members. Although it has matured alongside National Organic Program protocols, it maintains its grassroots commitment more than most third-party certifiers, and to have the best of both worlds, we in Maine, as farmers and consumers, are truly lucky.

About the author: John Bliss works at Broadturn Farm in Scarborough, which grows MOFGA-certified organic vegetables. He wrote about subsistence farming in the Ethiopian highlands for the summer 2016 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.