|

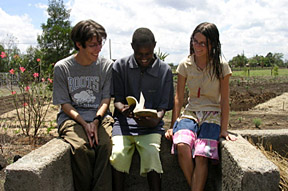

| Jesse Rusak (left), Raphael Nd’ung’u Kimani and Saima Sidik share a humorous moment looking at a book while sitting on a compost bin. Photo courtesy of Expanding Opportunities. |

by Saima Sidik

Saima Sidik of Lincolnville, Maine, and Jesse Rusak of Halifax, Nova Scotia, spent January to July 2006 in Kenya with an organization called Expanding Opportunities (EO, expandingopportunities.org). This non-governmental organization based in Brooks, Maine, facilitates the Joseph Waweru Home School (JWHS), which is an orphanage in Mangu, Kenya. The organization offers service journeys during which people can volunteer at the JWHS, experiencing Kenya’s culture while doing something more useful than tourism. Sidik and Rusak, for example, worked in the JWHS organic garden, wrote newspaper articles publicizing EO, experimented with and promoted solar cooking, finessed EO’s Web site, and tutored some of the JWHS boys in algebra. Here, Sidik writes about her impressions of agriculture in Kenya.

Once when I was cutting up potatoes, Pastor Waweru, the “father” at the JWHS, asked me, “Are those from here?”

“Yes!” I said. I was in North American mode, and thinking that by “here” he meant “Kenya,” the way I think of “here” as meaning “Maine” when I’m at home. In retrospect, I’m sure Pastor Waweru was referring to our garden.

|

| Saima Sidik plants kale in the Expanding Opportunities organic garden in Mangu, Kenya. Photo by Jesse Rusak. |

Many Kenyan families depend on their land to provide sustenance. Thus, “local produce” takes on a new meaning. Kenyans often grow most of their year’s supply of staple foods on their farms and raise their meat in their front yards. They might buy some food from neighbors, but the essentials for their lifestyles are almost always from within 20 miles of their homes. Treats such as mangos, which aren’t grown in arid regions, are transported from the Kenyan coast to inland towns, where they’re sold from small stands. Even these non-local foods are transported only from the other side of a small country, though; not from halfway around the world, like the bananas from Ecuador that I see in Maine supermarkets. (To read about preparation of local Kenyan foods, visit www.expandingopportunities.org/cookbook.)

Kenya also has supermarkets, in cities, to cater to the upper class that has moved away from farming. These feature pretzels from Italy, canned meals from India and cheese from France. Rural Kenyans see this food as foreign and extravagant. “Can you eat our food, or do you have to eat supermarket food?” my friend once asked me. I assured him that their food was fine and wouldn’t hurt me. The dichotomy that he and other Kenyans see shows how strange the ideas of potato chips and boxed lunches are to them. While eating locally reduces carbon dioxide emissions, lowers dependence on automobiles and is generally a good thing, Kenya’s environment is still suffering from its current agricultural setup. Halfway through my stay, I visited a national park about a half hour’s drive from my house. Inside the park’s borders were trees that had been there since before Kenya gained independence in 1964, with deep undergrowth hiding lions, leopards and antelope. But five minutes outside the park’s boundaries, I was back in a deforested, dry land whose soil has turned to dust. More Kenyan land is being cleared every day, either to make way for more crops or to produce charcoal and firewood, and this clearing is turning the country into a desert.

I don’t have any single solution to this problem. Importing goods and instating factory farms aren’t useful solutions. Teaching Kenyans space-efficient methods of farming could be helpful. Devising irrigation methods so that Kenyans can farm on a small area all year, instead of planting many acres during the rainy seasons, might also help.

Solar cooking is one way to reduce deforestation and desertification. Solar Cookers International (SCI, solarcookers.org) is an organization focused on promoting the use of solar ovens worldwide. Its main project right now is spreading the use of CooKits—cardboard apparatuses, consisting of four panels coated with reflective material, that focus sunlight into a plastic bag in the center of the panels. A cook can put a pot of food in the bag and use energy from the sun to cook. SCI has an office in Nairobi, and its employees do demonstrations throughout Kenya, explaining to their fellow Kenyans that by using CooKits, they’ll be able to reduce the amount of firewood and charcoal they need, thus helping to curb deforestation.

I tried to introduce CooKits to the JWHS, but found that Kenyans (at least the ones I was talking to) were very reluctant to try this new technology. Having piping hot food is a status symbol in Kenya. If your neighbor uses charcoal and cooks a hot meal in an hour, whereas you have to wait three hours for your solar cooker to provide you with your supper, then your neighbor appears stronger than you. He can afford to use more resources, whereas you’re stuck with second-rate equipment.

Unfortunately, Western influence in Kenya has exacerbated the country’s agricultural problems by inflicting a lot of our ideals of industrial agriculture onto it. Pesticide use is common in Kenya. Even people who can’t really afford these chemicals make sacrifices in order to buy them, because certain crops are considered impossible to grow otherwise. I had a terrible time trying to explain to my neighbors why I wouldn’t spray my tomatoes. “But caterpillars will eat them!” they kept saying.

“Yes, but a little damage to the fruits is better than a lot of damage to the soil,” I answered. Unfortunately, the green movement is almost unknown in much of Kenya (despite the successes of Nobel Prize winner Wangari Maathai and her Green Belt Movement, greenbeltmovement.org), and schools haven’t yet provided the level of education necessary to let people understand what’s at risk (which isn’t that different from some areas of the United States, frankly). Consequently, my neighbors just shook their heads and whispered about how crazy I was.

The Kenyans’ point of view is understandable. For people who rely on their gardens as much as my neighbors did, pesticides must seem like as great a miracle as antibiotics. It’s hard to see things on a long enough time scale to realize that pesticides are promoting the desertification of this fragile country, especially when you’re trying to feed your kids. I would love to go back to Kenya 10 or 20 years from now to see what has changed. The country seems to be at a turning point where people are finally starting to demand accountability from their government and better schools for their children. Food will be a very interesting issue in the next few decades. I hope Kenyans will retain their tradition of being self-sustaining instead of choosing to eat only supermarket food, and I hope they do so while maintaining the health of their land.

The JWHS Gardens

The JWHS gardens cover about ¾ of an acre. Since Kenya’s main crops are corn and beans, and that’s what people there like to eat, a lot of the garden space is devoted to these. Much of the remaining space is covered by sukuma wiki—a kind of kale (B. oleracea var. acephala) that Kenyans absolutely adore and eat in vast quantities. A small patch of garden consists of vegetables such as tomatoes, onions, carrots, cabbage and cucumbers. Some fruits, such as bananas and papayas, were planted a few years ago and aren’t mature yet.

For fertilizer, the JWHS uses what Kenyans call boma fertilizer. A boma is a pen for animals. Once a year, Kenyans cover the ground of their bomas with corn stalks. At the end of another year, they dig down past the partially decomposed corn stalks and take out the manure beneath them, which has now been composting for a year. This boma fertilizer is then mixed with the soil. We got our boma fertilizer from our neighbors, who owned several cows.

Aphids abound in Kenya, and I fought hard to control them through a combination of organic methods. Spreading ash on the plants seemed to deter them quite well, although it made the vegetables look a little unappetizing. My friend also taught me to make a broth out of garlic, hot peppers and the leaves of Mexican marigolds (Tagetes lucida) by soaking these in water for about a day. I sprayed this mixture on many plants, and it usually seemed to clear up any pest problems.

I never thwarted the ravenous ants that chewed up my tomatoes. I’ve never seen ants actually eat the fruits of a tomato plant in the United States, as they did in Kenya. I suppose in Kenya they, like the people, have to eat what they can get their hands (er… legs) on. – SS

Humanure

Flush toilets are not widely available in Kenya, as water and quality plumbing are both in short supply. The JWHS has chosen instead to install a composting toilet. The orphanage collects human waste, adds sawdust and hay to it, and allows it to compost in cement bins. After composting is complete, the resulting fertilizer is used on fruit trees and ornamentals. The system used by the orphanage is one recommended by J.C. Jenkins in his book The Humanure Handbook. According to Jenkins, it takes one to two thousand tons of water to flush one ton of human waste. The vast amount of water that goes into our toilets contributes to the 188 gallons of water that the average American uses every day. Composting toilets, if used correctly, are a clean, safe and environmentally sound alternative to flush toilets. – SS