|

| Salvador Cruz understands the importance of maintaining soil fertility organically. Photo courtesy of Karen and Paul Volckhausen. |

|

| Pineapple plants are good perennials for a permaculture-based farm because they help hold the soil and produce a crop in the second year. Photo courtesy of Karen and Paul Volckhausen. |

|

| Papaya is one of the crops that thrives in El Salvador’s climate. Photo courtesy of Karen and Paul Volckhausen. |

|

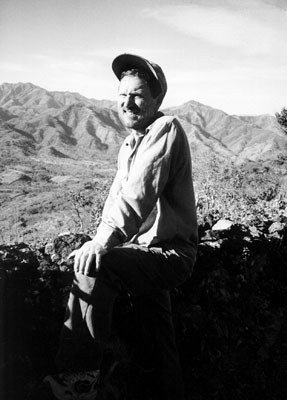

| Paul Volckhausen in El Salvador. Photo courtesy of Karen and Paul Volckhausen. |

MOFGA’s Salvadoran Sisters and a Relationship of Solidarity

By Karen and Paul Volckhausen

We recently returned from a four-month journey to El Salvador, where we had the privilege of living in a remarkable village in the northern department of Chalatenango. This fulfilled a long held dream of ours to live with the people from this region, sharing in their lives and learning more about their struggles. This interest in came in part from our involvement with the Bangor/El Salvador Sister City Project, which sponsors a sistering relationship between Bangor and Carasque, the village where we made our home. This relationship was initiated in 1991, during the years of the civil war in El Salvador, to help give hope and encouragement to a people trying to survive a terrifying situation. With the end of the war came a shift in the relationship that included accompanying their efforts toward sustainable development in a country that ignores the needs of its poverty stricken population. Through this relationship we were learning the value of cross border solidarity and receiving inspiration from a people who never gave up hope for achieving a just life.

Many delegations have visited El Salvador from Bangor, and several delegations have traveled to Bangor to share the reality of their lives with us. In 1989 Esmeralda Rivera, then the president of the non-governmental organization (NGO) CCR, was in Bangor speaking about her organization’s work in Chalatenango. Among the many groups she spoke with were Russ Libby and other representatives from MOFGA. She talked about the fledgling efforts of CCR working with another NGO, CORDES, to encourage campesinos (farmers) to convert to organic farming methods for the health of the land and the people. A striking part of this conversation was the discovery of the similarity of problems between peasant farmers in El Salvador and small organic farmers in Maine. From this the seeds of an idea were planted; an idea of organization-to-organization sistering to support and recognize each other’s work. In the realm of sistering, this would be an innovative and ground breaking project. An agricultural delegation to El Salvador in January of 2000 expanded this idea, and in April of 2001, the MOFGA board unanimously approved a sistering relationship with CCR (Association of Communities for the Development of Chalatenango) and CORDES (Foundation for Communal Cooperation and Development of El Salvador.)

Survival has always been on the edge in Chalatenango. The land is rocky and steep, the soil is poor. Monocropping has been the practice for centuries as campesinos grow corn and beans for consumption and to bring in a little money for family necessities. The weight of overpopulation, civil war and poverty has taken its toll on the environment; water sources are 100% polluted, the land 98% deforested. With deforestation comes the problems of massive soil erosion and loss of water sources, further endangering the sustainability of the land. Rather than attempting to address these problems, the Salvadoran government is embracing “modernization” through an attempt to industrialize the country. In effect, it is turning its back on agriculture and encouraging people to leave the land to work in the maquilas (sweat shops) where workers are underpaid, working under abusive conditions, and forbidden to organize. Complicating the situation even more are the free trade agreements that have allowed cheap grain from other countries to flood local markets, preventing farmers from earning sufficient money to survive. As a result, more and more people, desperate from lack of income and opportunities, are coming to the United States. With the drain of their best and brightest, many villages are in danger of becoming ghost towns. The problem is going to worsen if trade agreements such as FTAA, a NAFTA for South and Central America, are approved.

Strong efforts on the part of many organizations, including our sisters, are being made to find solutions to these very serious problems. CORDES is doing much to increase awareness of environmental issues. Through public talks given by CORDES technicians at village assemblies and the formation of ecology committees in the towns, people are being educated and educating each other about some of the major environmental concerns. Burning of fields, deforestation, harmful effects of chemicals and poisons, soil erosion, the loss of water sources, and improper disposal of garbage and trash are among the important issues discussed, with a focus on how they impact health and agriculture. Results of these efforts are evident. A municipal ordinance now bans burning. Some of the larger towns have trash projects that include burying of inorganic and composting of organic waste.

CCR and CORDES have been working hard to promote agricultural sustainability. Over the past five years they have worked with farmers to teach organic growing methods, crop diversification and successful marketing techniques. With individual farmers, they develop plans for their parcels, taking into account soil types and water availability. They have been instrumental in forming regional commercialization committees that deal with issues of processing, marketing and credit. In the micro region where we were living, they have developed a weekly farmers’ market, and they hope to form others in neighboring towns where farmers will have an opportunity to market their goods. While working regionally and nationally, they also have dreams of international marketing. A drying cooperative run by women buys excess fruit for processing. In the future, CORDES hopes to receive organic certification of these products and export them to other countries. The chief barrier to this dream is financial; they cannot afford the price for certification.

As they strive to make a living off their land, the farmers of Chalatenango are increasingly interested in the programs of CORDES. We were fortunate to have the opportunity to travel with a CORDES technician as he visited farms in our region and to see the many innovations taking place. The parcels we visited are being farmed organically. A key shift in practice is diversification of crops. Although corn and beans are still being grown for family consumption, a wider variety of vegetables, such as peppers, tomatoes, squash and cucumber are being grown also. Many farmers are converting from annual to perennial crops, mostly in the form of tropical fruit trees. Crops such as bananas and pineapple, which can be harvested in the second year are interplanted with mangos, oranges and other fruits that take longer to come into production. To deal with the steep grade of land, plants are cultivated on the contour, crops are terraced and living barriers are used. Drip irrigation is becoming more widespread for farmers lucky enough to have a water source. This is of great benefit, as it allows them to grow during the dry season, November through April. Generally they irrigate at the end of the day into the night to avoid the drying effects of the sun. They are also making their own compost, including worm composting. Periodic workshops at different farms give the farmers an opportunity to learn from each other.

Among the farmers we met, two remain deeply etched in our memory. Benigno Menjivar, at age 31, is one of Carasque’s visionaries. He fully understands that the future of his village and his country rests on the sustainability of the land and never ceases trying to raise the consciousness of his fellow villagers concerning this fact. He farms very steep land that has been in his family for generations. Relatively new to the program of CORDES, he has converted from corn to permaculture by planting fruit trees, natural barriers to prevent erosion, and thousands of pineapple plants along the contours of the slope. At the same time he is very involved in regional development through his role as a member of CCR, working on a micro-regional level, plus being a member of several committees that deal with sustainable development in the municipality. He realizes that this leaves less time for farming but makes this choice understanding that the work must go beyond individual efforts.

Likewise, the parcel of Salvador Cruz was a joy to tour. Four acres of a wide variety of healthy, organically grown crops, including cocoa, mangoes, pineapple, oranges, papaya, cashews and shade grown coffee, are a tribute to his love for the land. He sells his produce through a small store in his home. What a pleasure to watch him sit back and survey his own land with such intense feeling! He is an excellent example of continuing the tradition of farming through nontraditional methods to ensure a healthy future for the land.

We returned to Maine with a new appreciation for the problems campesinos in El Salvador face and the solutions they are working to implement. We also have an enhanced awareness of the importance of the sistering relationship that MOFGA has embarked on and the role we can play. We can see the possibility of many projects in the future. Delegations to El Salvador; tours for our sisters here in Maine during big events such as the Common Ground Fair; our representation at their biannual organic farming meetings; and fundraising to help them with their dreams of organic certification and market expansion. We are all working toward the same goals of healthy land, healthy families, a healthy society. Through our sistering project we can support and learn from each other as we endeavor to fulfill these goals.