|

| An organic farm in the Bacuranao River Valley, near Havana, Cuba, as viewed from 26th of July Cooperative’s headquarters. Jed Beach photo. |

By Jed Beach

The view from the hilltop headquarters of the former Empresa Pecuaria Bacuranao is just the sort of command-and-control, panopticon view to satisfy the manager of a large-scale, industrial farm. “All this below us was a giant dairy farm,” says Cuban agronomist Fernando Funes Monzote. “The government imported thousands of Holstein cows. This was a 13,000-hectare farm once.”

He sweeps his hand over the river valley that curls around the knoll on which we stand. Behind us is the old, concrete bunker headquarters. I imagine the previous managers admiring their command from there: the Bacuranao River meandering through a landscape of grain silos, tin-roofed milking sheds, red Soviet tractors patrolling the fields and doling out scientifically rationed pesticides and fertilizers, milk trucks leaving for nearby Havana, buses of farm workers headed for their urban communities, concrete post and barb wire fences, pastures filled with imported grasses and black and white cows. This farm was a model of industrial perfection, a page from a book called The Green Revolution Manual, owned and operated by the socialist state.

Today the milk sheds and silos are buried beneath palm trees and pernicious, thorny weeds, and orderly pastures have vanished beneath gray-green vegetation. In the midst of this expanse are a few clearings, and next to each clearing sits a concrete ranch house. These are pioneer farms of the post-industrial wilderness, members of the 26th of July Unit of Basic Cooperative Production, successor to the Empresa Pecuaria.

|

| The Bacauranao River Valley, with farmsteads in the foreground and the invasive marabou in the hills. Jed Beach photo. |

Now the Cooperative office sits in the old bunker, but its president, Ernesto Rebollar, spends most of his time in the valleys with farmers. While I wait in the office for Rebollar with Monzote, a young man studying for his doctorate, and Antonio Salinas, a livestock agronomist, we discuss our common enthusiasm for organic farming. I tell them how U.S. organic farmers try to prevent problems rather than having to treat them after they occur. They ask if rich American farmers have their own jets and airstrips.

I smile. “Not where I come from.”

Rebollar bursts into the room, shakes my hand and smiles. Fernando shows him what he brought – work gloves, grain sacks, whetstones, padlocks, alfalfa seed and other items that are difficult for a Cuban farmer to obtain. Ernesto reacts with joy and gratitude, then the two discuss fatality rates (“Sanitary Sacrifices”) from diseases. They examine spreadsheets of milk production of the Cooperative’s farms. They talk about markets and prices, ways to increase profit.

“We are looking to survey tourists,” says Monzote, “to find out how much they would pay for organic beef. We know that it’s the sort of thing tourists are looking for, and you could sell direct to hotels that way.” I tell them that we call that ‘niche marketing.’

Next we pile into Monzote’s Russian Lada, with its bumper sticker that reads, “Don’t Panic, Eat Organic!” in English. We drive toward the Bacuranao River Valley to visit one of the Cooperative’s newest, now typical farms: a small, organic, labor intensive farmstead that produces for local markets. If this sounds like the kind of farm that grassroots organic activists in the United States are championing, it is no coincidence. Cuba’s organic farmers are responding to a far greater urgency than their American counterparts, but they began with a similar discontent: the broken promises of industrial agriculture.

A Long History of Colonial and Industrial Agriculture

Despite the fertility of its soils, Cuba has not been agriculturally self-sufficient since Spain yoked its fortunes to the sugar industry in the mid-nineteenth century. Since then, Spanish colonialists, Cuban politicians and socialists, American captains of industry and Russian advisers have chased after fantasies of prosperity from cane. In the 1930s, they said, “Without sugar, there is no country.” After the Revolution, the economic planners considered diversifying Cuba’s agriculture, but industrialization brought their thoughts back to sugar. “The entire economic history of Cuba has demonstrated that no other agricultural activity would give such returns as those yielded by the cultivation of sugar cane,” concluded Che Guevara.

In 1963, Cuba signed a trade agreement in which the Soviet Union guaranteed petroleum and machinery in return for sugar. At last, the island would have access to the tractors and chemicals of the Green Revolution that U.S. investors had withheld.

“We’ll have so many bananas that we won’t sell them to you, we’ll give them to you,”

Fidel Castro promised a group of guajiros in 1967, adding that family farming was a tragic but necessary sacrifice in this quest. In the New Agriculture, workers would live in concentrated housing developments in the midst of vast fields, where they would enjoy electricity, indoor plumbing, and other comforts previously unknown in rural Cuba.

In the United States, green activists warned of the cataclysmic future, when industrial agriculture would ruin our natural resources just as the fossil fuels needed to sustain it disappeared. In Cuba, in 1990, the future happened, and they called it the Special Period. The Communist bloc collapsed, and Cuba lost its sugar markets as well as its source of machinery and fossil fuel. A massive economic depression ensued, and the entire agricultural system ground to a halt. Russian tractors fell silent, and exhausted soils could not support crops. Frustrated farmers watched as masses of short, squat marabou trees invaded depleted fields, as branches laced with interlocking thorns formed impenetrable walls. Within a few years, marabou covered almost 85,000 hectares of Cuban soil and more than half of all Cuban rangeland.

|

| The plants in this marabou thicket are 8 feet tall and have thorny, interlocking branches. Jed Beach photo. |

Invasive Plant Thrives on Greed

Marabou first appeared in Cuba during the sugar and livestock boom of the late nineteenth century. Since then it has been the evil twin of monocrop farming, as it preys only on weakened and damaged ecosystems. It gets shaded out in forests and does not grow on well-maintained cropland or pasture; it flourishes only when farmers disturb land, then let it sit fallow. Seeded within the thickets is a fable about human greed: Don’t plow more than you can handle.

In 1992, a group of veterans arrived in the Havana suburb of Santa Fe to start life after the armed forces – during the Special Period, when pensions were minimal. The government gave out land on the outskirts of town, hoping that the retirees could make it productive, feed themselves, and possibly produce a surplus. The land had been a large dairy farm that went under in the ’80s and hadn’t been working for almost eight years when the men arrived to find it covered with marabou. But beneath its thorny branches, the leguminous marabou had been enriching their soil via nitrogen-fixing bacteria in its roots. Leaves and fruit fell from the trees and began to build humus. In four or five years, a stand of marabou can make barren soil cultivatable.

However, marabou’s regenerative properties are best appreciated when you don’t have to cut any down yourself. For Cuban farmers, it will always be an enemy. One farmer I talked to, Juan Avila, had served in the army for 31 years. When he started farming here, the marabou were a foot wide each. “We cut them all down, with machete and axe. It took me a month to get my patch all cut down. Boy, it was hard work. I used to go home at night and pick the thorns out of my clothes and skin. Look, here.” He showed me the knuckles on his left hand, two of them swollen to twice their size. “That’s from the marabou thorns that got stuck in my hands.” Nine years later, he was still bearing the scars.

|

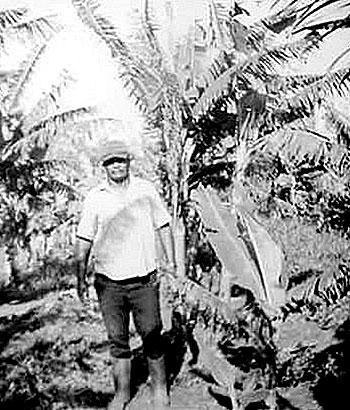

| Juan Avila: Juan Avila in his banana patch. Jed Beach photo. |

As one group of veterans hacked through the thickets, the soldiers could see five royal palms standing on the slope above them, reminding the former soldiers of a Revolutionary legend. When Fidel Castro and his group of insurgents crash landed on Cuba’s Oriental coast in 1957, they were attacked by dictator Fulgencio Batista’s troops and scattered. The would-be revolutionaries agreed to regroup beneath a stand of five palms. When those who had escaped the batistianos stood beneath the copse, Fidel asked, ‘How many guns do we have left?’ The answer: Sixteen. ‘How many men?’ Twelve. “And with that, we won,” said Juan Avila.

Patriotic, Organic Farming

Avila had served in the armed forces for 30 years after growing up in the Sierra Maestra Mountains, where his parents grew some coffee and small fruits and raised a few cows. Avila began helping his father with chores at age seven. He hauled water from a well 3 kilometers away. They worked 10 hours a day.

“Of the work, I remember very important things,” said Avila. “The fight of the plantings, the struggles against the weather, the low prices we got. But there was also a great enthusiasm, and a necessity too.”

Avila was part of the generation that came of age in the 1960s, when the Revolution was fresh and new and people talked earnestly of performing miracles. He joined the army at 15 and developed an unswerving patriotism that still serves him as he thinks, talks and acts in military metaphors. Everything is a struggle, a fight or a victory. Avila and his comrades call their new market gardens “Five Palms,” to commemorate this new revolution for a different age.

Now Avila’s generation is spread across the social spectrum and has had to compromise their lives with the present reality of Cuba, but many never question their paths nor their commitment to a more equal Cuba. “I came [to Five Palms] for the necessity of my country,” says Avila, scowling, then he adds softly, “Well, I like it. I like to watch things grow and know I’m part of it.”

Avila and his comrades at Five Palms engage in “the new battle” to produce food, as do many Cubans. They built gardens in cities and on abandoned State Farms while learning or relearning how to farm without machines and chemicals. They are the children of the guajiros, once pooh-poohed and brushed aside, who had persisted through the Green Revolution to preserve a locally adapted, low-input agriculture that was more resilient and sustainable than its would-be successor. They were the Cuban back-to-the-landers, who had made successful careers in the burgeoning industrial society, then chose to become farmers again.

“People from all the surrounding communities came here for help,” says Avila. “We were an example that yes, Cuba could do this. It was very important to prepare people for the new fight.”

They cut marabou with machetes, then plowed with oxen. They planted short-cycle crops, such as corn and squash, to break the marabou’s hold on the soil. Then they planted fruit trees and grass and began making compost with worms. The next year, they planted lettuce, tomatoes, medicinal plants, a few other small vegetables.

Help came. In 1994, agronomist Fernando Funes Aguilar (father of Fernando Funes Monzote) visited Five Palms, along with a California farmer from the American nonprofit, Food First! They brought tools, irrigation equipment and organic farming advice. Five Palms grew by leaps and bounds. By 1997, it had over 800 banana trees, guayaba and pineapple orchards, and a host of vegetables, livestock and medicinal plants, all grown in polyculture and fertilized with compost and legume rotations. The farmers dug a well and had a fish pond and a biodigestor. They are, by most measures, the ultimate “organic” farmers.

|

| A typical organic garden in Santa Fe. The banana trees (right) are planted around the perimeter to protect the annual crops (left) from windstorms. Jed Beach photo. |

They grew food for their families first, then began giving surpluses to local schools and children’s centers. In 1998, they began to sell their product at a farmer’s stand in Santa Fe, although they continued donating food to schools.

In 2000, disaster struck.. The government decided that their land would be better used as a municipal airport for the growing suburb. Workers cut most of the fruit trees and two of the original five palms to make a runway.

“It was for the good of Cuba,” says Avila, not criticizing but shrugging, as if to say, “What can you do?” adding, “It’s been frustrating.”

The men of Five Palms received new land – covered with marabou – on the hill above their old section. They cleared and planted their short cycle crops, as before.

“I will continue to do it,” says Avila. “I will continue to work until I lose my force. I like to farm. It’s a family tradition – we’ve always been from the fields.”

A Pioneer, Cooperative Farm

Monzote, Salinas, Rebollar and I hurtle in the Lado down the gravel road that runs through the middle of the Bacuranao River Valley. Derisabel Gonzalez Williams, the Cooperative’s Chief of Production, accompanies us. The farm we are going to visit, El Mango, is less than a year old, and the farmer, Hector Suarez, is having trouble. I am along to observe as the experts help, and I am excited: It is my last week in Cuba, and although I have visited many farms, all of them were established and well-maintained. This farm is still in the pioneer stage.

Before the sugar plantations and the Empresa Pecuaria Bacuranao existed, the valley was a fertile place, the black loam of the river banks supporting a profusion of bushes and wild orchids. Further from the river, the soil on the valley floor was red with iron and clay and was covered with native grasses and copses of palm trees – the tall and stately Royal palm, and the squat trunks of the palma barrigona that farmers hollowed out to make water tanks. In the hills the land was grey and dusty red, and palms flourished with such hardwoods as grey and stooped algorrobo.

By the time the Empresa went under, chemicals had bleached the reds and blacks out of the soil and left a dull, grey-white sand. Only two families remained. Since then, the 26th of July Basic Unit of Cooperative Production has slowly grown to 56 families living on 24 small, diversified farms.

Simply put, in a Unit of Basic Cooperative Production (UBPC), each farmer has a plot of land and a contract with the state – for milk and beef, in the case of the 26th of July. Farmers can manage their lands as they see fit, as long they meet the state quotas. They usually have an auxiliary outlet for fruits and vegetables at a nearby, urban farmers’ market, where they can set their own prices according to supply and demand. This is often the more lucrative venture. The Cooperative negotiates contracts and receives credit and technical services as a group. Profits go to a single bank account, but each farm receives a share according to its production. Some of this revenue must be reinvested in the farm; farmers can invest or spend the rest as they see fit.

Rebollar believes that the UBPC is the vanguard of Cuban agriculture and will replace the State Farm paradigm as organic farming replaced the Green Revolution. While they must solve members’ problems first, “the objective of all cooperatives is the same: How to resolve the problems of alimentation in the socialist system,” he says. “The Cooperatives will resolve the problem of feeding Cuba.”

As president, Rebollar, who is also a veterinarian and a visionary optimist, represents the Cooperative to the outside world. Technician Derisabel Gonzalez Williams works most closely with its farmers, paying close and often skeptical attention to the details of survival. For her, marabou is not a miracle-working legume but a thorny enemy. The Cooperative’s inability to clear more marabou frustrates her. “We don’t have enough machetes, even,” she tells me.

Williams is eager to expand the Cooperative’s farmers’ markets, to get a better road through the valley. Her goals are more short-term and concrete than Rebollar’s. “We want to improve the lives of the people who live here. Not to have a hotel for their house, but to have a television, a refrigerator – the same standard of living as in the city.”

The Cooperative’s beef fetches one peso (about four cents) per kilo, she tells me.

“How much does it sell for in the farmers’ markets?” I asked.

“I wish they sold it in the farmers’ markets!” she exclaims. “All the beef goes to tourism, where it fetches dollars” – reminding me of my many trips to the farmers’ markets near my apartment. In the markets, the successes of organic agriculture seemed distant compared with the needs of consumers. I found that urban Cubans were largely ignorant of the country’s organic movement. Ration cards provide each Cuban with some basic staples, but to eat a balanced diet, everyone must shop. Those who are lucky enough to have access to American dollars can go to air-conditioned supermarkets and buy things like beef, as tourists do. Beef is sold only in dollars because dollars mean higher profit margins for the state. In theory, these higher revenues return to the state’s socialist programs, such as health care and education.

Behind a small, concrete ranch house, we find Hector Suarez leading his team of oxen, pulling a wooden cart of sugar cane that he has just cut as forage for his cows. Suarez struggles against the wilderness and depleted soils left by agroindustry. He has sown a pasture grass called pasto estrella, although many bald or weedy patches still exist. The vibrant green king grass and sugarcane in his forage area look healthy. Marabou still reigns in many places: His land suffered heavy artificial fertilization for almost 30 years and lacks organic matter.

Salinas leads Suarez around his farm and talks in Business Mode. “You will need to get some organic matter in those pastures.”

“But I haven’t had the time. My crops haven’t made enough,” Suarez replies.

“A good farmer doesn’t need to fertilize his pastures, his cows do it for him,” chides Salinas.

“But I can’t put my cows in the main pasture until after five. The sun beats on them, they get too hot.”

“Then … you make shade. Plant Leucaena. In eight months, there’s shade.” Leucaena is a leguminous tree, popular with agronomists because the rhizobial bacteria in its roots add nitrogen to the soil, and its sparse canopy permits grass to grow beneath it.

“I planted Leucaena,” protests Suarez, “but it didn’t take.”

“Try again.”

In the milking parlor, everyone acknowledges that Suarez needs a new floor and hopes that the Cooperative can manage the funds.

When he started farming, Suarez received 25 cows and the right to use a little over 200 acres of degraded land from the government, and a mandate to produce milk for the socialist system. He tells Rebollar and Salinas that he cannot manage such a large milk herd effectively. He has to milk all 25 by hand, twice a day. His pastures cannot support that number, either. He wants to reduce his herd to 15, to focus on quality rather than volume. He wants to sow more vegetable crops, to see banana trees under the royal palms at the edge of his holdings.

Suarez tells me that he was a worker of the Empresa here. When it shut down, he left, but “I returned because I liked the work. I liked to farm, to make things grow.” He had no experience managing his own farm but is learning. He has more freedom to make decisions than he did on the State Farm, “more possibility – more chance to be happy.”

“In a few years,” says Salinas, “this farm will be a paradise.”

About the author: Jed grew up in Wilton, Maine, the son of back-to-the-landers. He is now based at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. He was the lead writer for the Maine Department of Agriculture’s Maine Food and Farms Resource Guide; and he spent three months traveling and studying in Cuba.