|

| Dr. Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani and Dr. Margaret Skinner of the University of Vermont gave a fascinating talk about saffron, the world’s most expensive spice, at MOFGA’s Farmer to Farmer Conference. English photo |

By Jean English

Dr. Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani and Dr. Margaret Skinner of the University of Vermont gave a fascinating and entertaining talk about saffron at MOFGA’s 2019 Farmer to Farmer Conference. Their team at UVM also includes Bruce L. Parker and Paul Rees. Ghalehgolabbehbahani, the main presenter, explained that his last name became a combination of his middle and last names, Ghalehgolab and Behbahani, due to an error on his passport. We refer to him as Arash in this article.

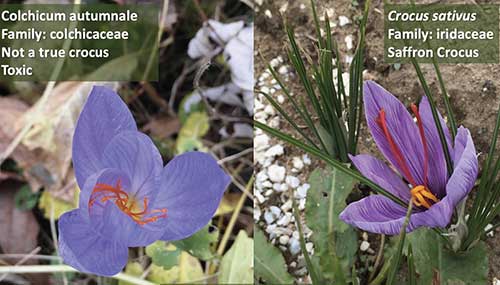

Saffron, the world’s most expensive spice, is the dried stigmas of flowers of the fall blooming saffron crocus, Crocus sativus, in the family Iridaceae, said Arash. That genus includes 90 species, he said, but only C. sativus is saffron. Don’t eat products from the autumn crocus, Colchicum autumnale, a member of the Colchicaceae family, he warned; it is not a true crocus and is toxic, but it blooms at the same time as C. sativus.

The saffron plant probably originated in Greece or Crete and has been cultivated for over 3,500 years. Saffron is used as a culinary spice, medicinal herb, medicinal extract with anticarcinogenic and antidepression effects, a perfume, ornamental plant, fabric dye and liqueur.

The spice brings a range of $3,000 to 9,000 per pound worldwide outside of the United States, while U.S. growers are getting $25 to 75 per gram ($11,350 to $34,000 per pound). It is expensive because most processing (removing the stigma) is done by hand and the yield is low: 150 to 170 flowers produce a gram of saffron, and it takes 4,000 blooms to produce 1 ounce (28 grams) of saffron. The average saffron yield is less than 4 pounds per acre.

The Backstory

Arash is originally from Iran, which produces 90 percent of the saffron in the world. He thought this might be a good crop for high tunnels in Vermont, so when Skinner got funding to research the spice, Arash started a post-doctoral project there.

Phytogeographically, most Crocus species occur within the Mediterranean region extending eastward into the Iran-Turanian region, said Arash. Now the major producers are Morocco, Spain, Italy, Greece, Iran, India and Tajikistan – although the Pennsylvania Dutch started growing C. sativus in the United States as early as 1700s. Producing and cooking with saffron is part of their culture, Arash reported.

The United States imported 46 tons of saffron in 2016, and imports are estimated to triple by 2025, so he thinks a market exists for the crop here.

Over 110,000 acres (over 80 percent) of the world’s saffron growing area is in Khorasan Province in northeastern Iran – yet Iran has only 4 percent of the market since other companies buy, repackage and resell saffron as their own product. Soils in this area are characteristically below 1 percent in organic matter, so Arash thinks that the relatively high level of organic matter (more than 5 percent) of some soils in northern New England and other U.S. regions could be good for saffron production. He said one study showed that humic acid released from organic matter and compost to the soil can increase saffron productivity up to 50 percent.

|

| Saffron is the dried stigmas of flowers of the fall-blooming saffron crocus, Crocus sativus. English photo |

|

| Arash warned Farmer to Farmer participants not to confuse Colchicum autumnale, the autumn crocus, with Crocus sativus, which produces saffron. Both bloom at the same time, but C. autumnale is not a true crocus and is toxic. Photo courtesy of Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani |

Saffron Production

The saffron production cycle begins with corms planted from mid-August to mid-September. Then, 40 to 50 days later, flowers appear for one month, from mid-October to mid-November. Growers must harvest the flowers every other day and separate the stigmas on the same day, requiring some labor during the two- to four-week blooming season. After bloom, the plant is dormant for months. With warmer weather, secondary corms form on the mother corm. The plants are dormant during the summer, so no leaves emerge then. Climate and planting density determine how long the secondary corms remain in the ground – typically three to eight years.

Noting the large number of small farms and the closing of many dairy farms in New England, Arash said that “diversification is key to the survival of small family farms.” Saffron has been shown to survive New England winters; the U.S. saffron market in 2018 was estimated at over $60 million; and the greatest labor demand for saffron occurs in October and November, when most field work is over; so the crop could fit into New England growing operations.

Planting

At first, Skinner and Arash did not think the corms would survive outdoors in a Vermont winter, so they wanted to determine whether saffron could be produced as a high tunnel crop. Arash sourced corms, 9 to 10 cm in circumference, from Pennsylvania in 2015 and from the Netherlands in 2016. He planted them by hand in raised beds and in milk crates between August 25 and September 1.

The researchers used milk crates because they are inexpensive (often free) and readily available, have a suitable depth for growing saffron, are lightweight but sturdy and durable, and they protect corms from rodent predation. Also, they are easy to move, so growers can start other high-value crops such as tomatoes in the spring. In September they can return the crates to the tunnel for saffron production. Arash said to keep crates on the ground, not on benches, in winter so that cold doesn’t kill the corms.

The 11-inch-tall milk crates were lined with weed cloth, and then 4 inches of topsoil were added to each crate. Corms were planted at a density of 118 corms/m2 (about 11 per square foot) in the crates and in raised beds. Then the corms in the crates were covered with 2 inches of topsoil and 4 inches of perennial potting mix.

For raised beds, Arash installed hardware cloth in 2016 to exclude moles and then added 4 inches of topsoil. He planted corms 2 inches deep in the topsoil and covered that with 4 inches of perennial potting mix.

Crates and raised beds were watered from above. Skinner said they are still determining when and how much to water milk crates in summer and whether to insulate them over winter.

Arash noted that growers can plant by dropping corms in a hole made with a soil auger. “We usually plant at a depth of 6 inches. You can go 7 to 8 inches in a colder, sandier soil.” If planted too shallow (4 or 5 inches), baby corms, which form on top of the mother corms, will be close to the soil surface after a few years.

The Vermont researchers are also trialing saffron crocus outdoors. A video of that planting process appears at https://www.uvm.edu/~saffron/. Large commercial growers use a saffron planter, said Aresh, which is like a tomato planter.

Harvest

The researchers harvested flowers by hand every two days from October 12 to November 20. They separated stigmas, stamens and petals and dried them in an oven at 50 C for one hour. (Vegetable dryers also work, said Arash.) They recorded fresh and dry weight of each part and assessed saffron yield and quality and corm yield. Mother corms die after a year, and secondary corms continue production for following years, so the number and quality of corms produced is important.

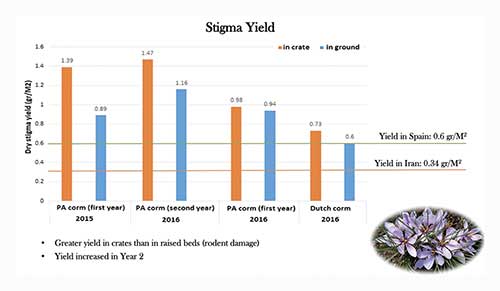

Yields in Vermont were good – sometimes three times greater than in other saffron producing areas. (See graph.) The researchers expect even greater yield in the second year of production. They attribute the greater yield in Vermont to good soil fertility and soil moisture and to protection from rain and wind in the high tunnel.

Skinner mentioned one couple who planted 2,500 corms outdoors in 2018 in a somewhat raised bed in a somewhat heavy soil, 20 miles south of Burlington. Yield was low (60 grams) in the first year, but they expected at least twice that for 2019. “So the corms do survive in the soil even without mulch or high tunnels over winter,” Skinner said, “but yields in high tunnels are considerably better.” Arash noted that in the summer, dormant corms can be covered with a black tarp to minimize weeding. One grower in the audience said that he grew zucchini during the summer over his saffron plot.

The most difficult part of the harvest is separating the stigmas from stamens, said Arash, noting that a machine is being developed to do that. In Morocco, blowers separate stigmas from chopped flowers.

|

| Yields of stigmas in Vermont exceeded those produced in Iran and Spain. Graph courtesy of Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani |

|

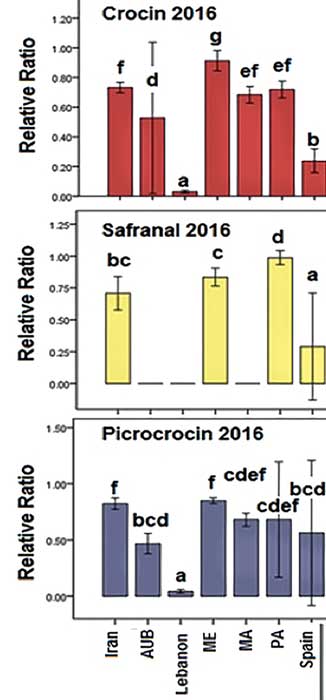

| The Vermont researchers obtained saffron from a store and from Vermont, Maine, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania growers in 2016 and compared levels of three chemical components: crocin, picrocrocin and safranal. Graph courtesy of Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani |

|

| In addition to producing saffron, C. sativus also produces saleable corms, which are sometimes more lucrative than the spice. English photo |

Quality

The International Organization for Standardization certifies saffron as class A, B or C, based on three chemical components: crocin, which imparts the red color to the stigmas; picrocrocin, which imparts the unique flavor; and safranal, which imparts the aroma. Results (see graph) from a store and from Vermont, Maine, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania growers in 2016 showed that crocin (which has anticarcinogenic effects) levels varied among Vermont samples; that the sample with the highest crocin level was from Maine; and the lowest concentration was from a sample stored since 2015. Corms from Pennsylvania produced higher concentrations than those from The Netherlands.

Safranal concentrations were very low in many samples, and picrocrocin levels for Vermont samples were generally similar to those from Iran and Spain.

A sample that Skinner bought in Lebanon and that was packaged in Switzerland was clearly adulterated, said Arash, noting that saffron is the most frequently adulterated spice in the world. “Mexican Saffron,” he said, is actually safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), a frequent filler or fraudulent product. “So we have the opportunity to introduce American saffron as a quality product,” he noted. “Persian people say Persian saffron is the best in the world. Same for Spanish people. Welcome to the party, Americans!”

Corm Yield

Treatment # primary corms 2015 # secondary corms 2016 Av. wt/corm 2015 Av. wt/corm 2016

In ground 465 407 11.2 grams 10.3 grams

In crates 465 756 11.2 grams 7.7 grams

As the table above shows, the researchers harvested almost twice as many secondary corms from crates than from raised beds; rodent feeding was a major factor in raised beds. Corms from raised beds were one-third heavier than those from crates, which suffered from soil moisture deficits.

Larger corms produced more flowers in year 1 but not greater yield. Arash noted that corms are sold according to circumference, from 7 to 10 cm. Larger corms are more expensive and are not worth the added cost, he said. The UVM trial showed that in the second year of production, plots with small corms produced more flowers.

Arash is collecting data on saffron yield, corm survival and reproduction from growers in three hardiness zones of Vermont (5a: -20 to -15˚F; 4b: -25 to -20˚F; 4a: -30 to -25˚F). In all zones, flowering peaks for two to three weeks around October 24 to November 5.

Pests and Diseases

Small mammals eat crocus leaves and corms and are a greater problem in the ground than in crates. Arash said that Mennonites top their plots with crushed oyster shells to control rodents, and that rodents didn’t eat crocus leaves in plots where he applied crushed oyster shells.

Diseases include Aspergillus niger, Penicillium sp. and Cochliolobus sp., and bulb mites (Rhizoglyphus robini) eat the bulbs and provide entry points for secondary infections from fungi.

Marketing

“Remember,” said Arash, “there are two products, the spice and the corms, which make more money for growers. In the field, 150 to 160 flowers produce a gram of saffron. In the high tunnel in the first year, 130 flowers produced a gram of saffron. If you want to be a corm producer, high tunnels and greenhouses will probably be better for that.”

Corms sell for 25 to 30 cents each, produce two to eight secondary corms the year after planting and are productive for three to six years. Arash doesn’t like to keep the crop beyond four years because of the potential for disease.

Skinner said that value-added products probably will be the way to make the most money from saffron. People add it to beer and honey, make saffron honey, and infuse gin with the petals to make a purple-colored liqueur.

Arash noted that bees and butterflies love saffron pollen, and he mentioned that one person was selling saffron pollen in the Boston area as natural dye.

Stigmas must be dehydrated to form saffranal. Asked if the stigmas can be dried legally in a certified kitchen, Skinner said that varies from state to state and depending on quantities. “We need to look into it more,” she said. The dried product can be stored and sold the following year.

One Farmer to Farmer attendee asked if saffron might be sold as pick-your-own? “Maybe,” said Skinner. “Then they [the customers] can do the drying.”

Those interested in producing saffron can learn more from The North American Center for Saffron Research & Development (https://www.uvm.edu/~saffron/).

Support for the UVM Saffron Research Project has been provided by the UVM College of Agriculture & Life Sciences, Peck Electric and Roco Saffron. Thanks to Arash for providing his PowerPoint for this write-up.