| What is dementia? Dementia is a group of symptoms characterized by a decline in intellectual functioning severe enough to interfere with a person’s normal daily activities and social relationships. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia in older persons. https://nihseniorhealth.gov/alzheimersdisease/faq/faq2a.html What is Alzheimer’s disease? Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older people. It is marked by progressive and, at present, irreversible declines in certain cognitive functions. These impairments may include declines in memory, time and space orientation, abstract thinking, the ability to learn and carry out mathematical calculations, language and communication skills, and the performance of routine tasks. https://nihseniorhealth.gov/alzheimersdisease/faq/faq1a.html – National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the National Library of Medicine (NLM), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). |

by Lucie Arbuthnot

Is there anything we can do to lower our risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease? This question was far from my mind a decade ago when I wrote in these pages about the pleasures of growing winter-hardy chicories in my Sanford, Maine, garden. But a decade ago my mother hadn’t been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and my life hadn’t changed forever.

Following her diagnosis I left a 25-year career as a college professor to join the Maine Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association. As the organization’s statewide educator, I traveled from Kittery to Fort Kent and from Jackman to Eastport to lead workshops about Alzheimer’s disease. I spoke to healthcare professionals, the general public and families like mine who had a loved one on this challenging path. One of the most frequent questions I was asked was whether we could do anything to prevent this dreaded disease.

What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s is a chronic disease, meaning that it is a long-term disease and – unlike the mumps or chicken pox – it is not caused by an outside infection and cannot be transmitted through personal contact. While the central cause of Alzheimer’s is still unknown, its physical manifestations are clear. Persistent short-term memory loss is the first symptom, followed by difficulties with everyday tasks, such as following a recipe or balancing a checkbook. As the disease progresses over time, lasting an average of eight years, people face challenges with personal care and communication. In the final stages patients need total care, and the loss of brain function ultimately results in death.

As with other major chronic conditions – including heart disease, stroke, diabetes and several kinds of cancer – advancing age and a family history are important risk factors. While there are few satisfying alternatives to living longer, and we can’t change our family history, we can take several concrete steps to reduce our vulnerability to these diseases. Foremost among them are simple lifestyle choices, including physical activity, eating a healthy diet, maintaining a normal body weight and not smoking. For Alzheimer’s, staying mentally active is also essential.

Physical and Mental Activity

Physical and mental activities top the list for Alzheimer’s prevention. A 2005 Finnish study showed that middle-aged people who engaged in leisure-time physical activity at least twice a week halved their likelihood of developing the disease 20 years later. A 2006 University of Washington study found that even middle-aged couch potatoes could make up for lost time. People 65 years and older who engaged in 15-minute sessions of physical activity three or more times a week reduced their risk of dementia by about 40 percent. These were not seniors running marathons: Their activities included such low-impact pursuits as walking, stretching, calisthenics and swimming.

Mental activity – the “Use It or Lose It” approach – is also a central strategy for protecting the brain from cognitive decline. Studies in the 1990s showed that higher levels of education reduced people’s later risk of Alzheimer’s. More recently, researchers have also noted cognitive benefits for mentally stimulating everyday leisure activities. In a 2002 study, scientists surveyed 800 Catholic nuns, priests and brothers ages 65 or older. Those who were most engaged in reading books or the newspaper, playing card games and going to museums were about half as likely to develop Alzheimer’s as those who were least engaged in these activities.

What kinds of mental activities are most helpful? More recent studies are expanding the list of things we can do to benefit our minds. They include gardening, do-it-yourself projects, keeping mentally active at work, taking classes, traveling, volunteering, participating in politics, being involved in religious activities and playing a musical instrument. It’s increasingly clear, however, that even these longer lists are far from exhaustive. “Any kind of active, deliberate learning seems to challenge the nervous system in uniquely fruitful ways,” concludes Jeff Victoroff, M.D., author of Saving Your Brain, if it is “exciting enough, and pleasing enough, to keep us motivated and engaged on an ongoing basis.”

What about watching TV? Some television programs stimulate our critical thinking, but passive TV watching has the opposite effect. Researchers in 2005 found that for each additional daily hour of television viewing when people were middle-aged, their later risk of developing Alzheimer’s increased by 30 percent.

Healthy Nutrition

Studies about the role of nutrition for brain health are ongoing but, so far, have been less conclusive – partly because dietary studies are notoriously difficult to conduct. Few people are eager to spend years on restricted diets in order to test their potential health benefits. Nutritional supplements – such as vitamin pills – while easier to test, do not affect the body in the same ways as whole foods. And despite the media’s eagerness to publicize the cognitive advantage for mice that drink apple juice or for dogs that eat vegetables, evidence for humans is still lacking.

Funding challenges also influence dietary studies. Pharmaceutical companies sponsor clinical trials that cost millions of dollars if these show promise of financial profit. Meanwhile, other researchers compete for scarce governmental funds to demonstrate the effects of simply eating a healthy diet.

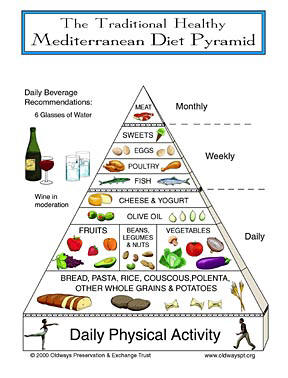

Epidemiological studies, which examine the prevalence of a disease in a given population, are an alternative to costly clinical trials. The “Seven Countries Study,” for example, was started in the 1950s to explore why some countries had lower rates of heart disease than others. Results showed that heart disease among inhabitants of the Mediterranean island of Crete was a small fraction of that in the United States. Researchers attributed much of the difference to the Cretan diet – one that was high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains and olive oil, that included more fish than red meat, and was consumed with a moderate amount of wine.

This same Mediterranean Diet is now being investigated for its possible role in Alzheimer’s prevention. Several studies have analyzed individual components of the diet, especially the fish and vegetables rich in healthy omega-3 fatty acids, but results have been mixed. In 2005 a U.S. government-sponsored review of hundreds of scholarly articles concluded: “Although the lay press and commercial advertisements have purported that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial for cognitive function and the treatment of dementia, we were unable to find strong evidence to support these claims.” A comprehensive British study published in 2006 also found “no good evidence to support the use of dietary or supplemental omega 3 PUFA [polyunsaturated fatty acids] for the prevention of cognitive impairment or dementia.” Both studies did, however, note a “trend” toward cognitive benefits for fish consumption, and new studies are underway. Stay tuned.

|

| Heart disease occurs much less among inhabitants of the Mediterranean island of Crete than among U.S. citizens. Researchers attributed much of the difference to a diet high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains and olive oil; with more fish than red meat; and with a moderate amount of wine. Researchers at Columbia University later found that New Yorkers’ whose diets most resembled the Mediterranean pattern had a 40% lower rate of Alzheimer’s Disease than those whose diets least resembled it. Other studies have had varying results. Illustration courtesy of Oldways Preservation & Exchange Trust, © 2000; used by permission. https://oldwayspt.org/index.php?area=pyramid_med. |

Other researchers are looking not only at individual ingredients – mostly fish and vegetables – but also at Mediterranean-style diets as a whole. Studies indicate that a Mediterranean diet can lower the risk of cardiovascular disease, some forms of cancer, and overall mortality. Could it also help protect the brain from Alzheimer’s?

Researchers at Columbia University published evidence in 2006 that it could. They divided a cohort of more than 2,000 New Yorkers into thirds based on the extent to which participants ate a Mediterranean-style diet. Results showed that the top third – people whose diets most resembled the Mediterranean pattern – had a 40% lower rate of Alzheimer’s compared with people in the lowest third.

Medical Risk Factors

Lifestyle choices are the first line of defense for reducing our risk of Alzheimer’s. As with other chronic diseases that disproportionately affect the elderly, however, medical conditions can also influence our vulnerability. Evidence of this connection was highlighted in 2005 by a long-range study in California. It tracked the health status of nearly 9,000 people over a 30-year period from their 40s to their seventies. Results indicated that midlife high blood pressure increased the later risk of Alzheimer’s by 24%, smoking by 26%, being overweight by 35%, having high cholesterol by 42% and diabetes by 46 percent.

Studies in other countries have reached similar conclusions. Scientists at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden reported in 2005 that middle-age obesity, high blood pressure and high cholesterol each roughly doubled the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease two decades later. When all three conditions were present, the risk increased about six-fold.

Not everyone is affected by these medical conditions, but my own mother’s situation illustrates their importance. She was university librarian and avid gardener, and she remained intellectually curious and physically active all her life. She was also committed to healthy nutrition and ate generous amounts of fruits, vegetables and fish. She even sidestepped the butter-vs.-margarine debate by using only olive oil on her morning toast.

But she still had serious health challenges, including high cholesterol, high blood pressure and a family history of Alzheimer’s disease. She started showing lapses in short-term memory when she was 78, and was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in her early 80s. Her physical and mental activity, as well as her healthy diet, likely delayed the Alzheimer’s symptoms. Nevertheless, even these beneficial lifestyle choices could not finally outweigh the influence of her medical conditions. She died one month shy of her 90th birthday.

Is there a special message here for Maine’s organic farmers and gardeners? The good news is that we tend to be physically active during our adult years, and we don’t turn into couch potatoes simply because we’re eligible for Social Security. We also keep our minds active by figuring out seed selections, crop rotations and pest reductions. If we eat our own homegrown food, our diets are surely healthier than most. Our remaining challenge may be to monitor key medical conditions – especially blood pressure, blood sugar and cholesterol levels – that can influence our risk of Alzheimer’s disease. And remember, it’s a win-win situation: lowering our risk of Alzheimer’s significantly lowers our risk of other leading causes of death and disability.

True, there are no guarantees. Nonsmokers can develop lung cancer and fitness gurus can be felled by a heart attack, but our ability to significantly cut our risk of Alzheimer’s and other chronic diseases remains the compelling message.

When Should We Be Concerned About Memory Loss?

Many people worry that Alzheimer’s disease is just around the corner when they lose their keys or can’t remember someone’s name. But we lose things at any age, and the “tip-of-the-tongue syndrome” is common – indeed normal – as we get older. Still, those who worry about Alzheimer’s are in good company. A 2006 survey showed that Alzheimer’s is second only to cancer as the disease Americans fear the most.

If you are concerned about your memory or that of a loved one, there are concrete actions you can take. Getting a solid diagnosis is important, because serious memory loss can be caused by conditions other than Alzheimer’s disease – including depression, vitamin deficiency and medication side effects – all of which, unlike Alzheimer’s, are reversible. Specialized clinicians can accurately identify the reasons for memory loss in 90 to 95% of cases, and Maine’s multidisciplinary memory clinics are excellent places to look for qualified answers. The Maine Alzheimer’s Association can provide a list of clinics, and it is the central resource for other information, support groups and educational workshops for people with memory loss and their caregivers throughout the state. You can reach the Association in Portland at 1-800-660-2871.

What if someone you know already has Alzheimer’s disease? On this topic my mother’s journey taught me far more than my years of research. Even as I watched her frustration with everyday tasks, her struggle with forgetfulness and her fear of abandonment, I realized that she never lost her core identity. When I stopped reminding, explaining and correcting, and focused instead on what she had left rather than on what she had lost, we were able to continue having a meaningful – indeed, a wonderful – relationship. We could still listen to familiar music and sing favorite hymns, reminisce about family and friends, chat in French, and share joyful laughter and warm hugs. Through our journey together I learned how much less our personhood is defined by our head than by our heart.

©2007 by Lucie Arbuthnot.

Following her mother’s death in 2004, Lucie left the Maine Alzheimer’s Association in order to share her passion for preventing Alzheimer’s disease with audiences nationwide. When at home, she still grows winter-hardy chicories in her Sanford garden. She can be reached at [email protected].