By Roberta Bailey

The hardy kiwi, Actinidia arguta, is a part of Maine’s heritage. Tucked away on coastal estates, climbing on the walls of College of the Atlantic, and entangling trees in Acadia National Park, these highly ornamental, rugged vines are reminders of bygone days when ship traders brought unusual plants from Asia back to the gardens of coastal estates.

As many as 20 years ago, a local resurgence of interest in the plant kindled when local plant enthusiasts discovered the delicious fruit that the vines bear. Over the years, interest in growing the fruit has broadened. Some growers have had success, but many have failed to get the tender young plants well established. With a few helpful hints and some extra care, many Mainers could enjoy an abundant supply of delicious fruit with vitamin C levels 10 times that of citrus.

Along with 36 other species of climbing woody vines, hardy kiwis are members of the Actinidiaceae or silver vine family. Native to Japan, Korea, northern China, and Siberia, they are cultivated as an ornamental and edible fruit. In the wild, the vines grow as an understory plant high in the forest canopy. Native peoples harvest hundreds of thousands of pounds of the delicious fruit as it drops to the forest floor.

Three species are commonly cultivated in North America. Actinidia deliciosa is the fuzzy, egg-shaped kiwi available on supermarket shelves. In the early 1900s, small amounts of this fruit were being shipped to the West Coast, until World War I shipping and import restrictions made New Zealand a mid-point between China and the United States New Zealanders began propagating and selecting for better adapted strains of the ‘Chinese gooseberry.’ They began exporting fruit, renamed as ‘kiwi’ in the 1950s, launched an aggressive educational marketing campaign in the 1980s, and the rest is history.

Meanwhile, two lesser known species quietly vined away. Actinidia kolomitka is the hardiest of the kiwis, tolerating –40 degrees Fahrenheit. The variegated white, green and pink leaves make it a highly valued ornamental. The small, smooth-skinned, green fruit are delicious.

Actinidia arguta is the best known and most widely available of the hardy kiwi plants. Also known as tara or bower vine, it is hardy to –25 degrees Fahrenheit. The sturdy vines with dark foliage on red petioles can reach 50 to 100 feet. Originally grown for its fragrant, cream colored blossoms that open in June, it is also known for its smooth-skinned, grape-sized, green fruits whose flavor is similar to but fuller and sweeter than that of commercial kiwi fruit. One vine can yield over 100 pounds of fruit.

Establishing Plantings

Hardy kiwis are dioecious, needing both male and female vines for pollination and fruit set. One male plant can pollinate four to six females. A few plants are monoecious, having the ability to pollinate themselves, but even these will yield better when a male pollinator is nearby, ideally within 20 or 30 feet, although some growers have had success with males that are 40 feet away from females. Male plants are more vigorous but less hardy.

Establishing hardy kiwis can be a challenge in Maine. They need some shade and wind protection, ample sun, and frost protection when young. One taste of the fruit will convince most gardeners that they are worth the extra effort. Being an understory plant in the wild, tender, young Actinidia are used to some shade. Actinidia arguta prefers 20% shade, while A. kolomitka thrives on 70 to 80% shade. They also need six to eight hours of sunlight to set fruit buds. Kiwis tend to leaf out early, leaving vines and developing fruit buds susceptible to late spring frosts. As herbaceous vines, protection from wind is important to avoid transpiration stress.

In a cultivated setting, finding a site that can meet these requirements is one of the keys to success. Maine is at the northern range of the species with respect to sunlight; more sun may be needed for good fruiting and growth. In more southerly locations the vines may need protection from the intense midday sun. A simple structure of chicken wire wrapped with polyester row cover will protect young plants from wind and frost. A site with a buffer of trees or buildings is beneficial. A northerly slope encourages later leafing. Transpiration problems in young plants can be lessened by adequate root development. Many growers are having greater success by leaving their hardy kiwi plants in pots for two years, giving the plants time to establish substantial root systems in a protected location.

Hardy kiwis thrive in light, well-drained soil that is rich in organic matter. They can also thrive in less than ideal soil, as long as it is not too wet or extremely sandy. Heavy clay soils stunt root growth and can lead to crown rot. Extremely sandy soil does not provide enough moisture. Plant in a raised bed if drainage is a problem. A spring dressing of compost and well-rotted manure should supply ample nutrition. Kiwis require high levels of magnesium (2 oz. per 100 sq. ft.) and potassium (1/2 to 3/4 lbs. per 100 sq. ft.).

|

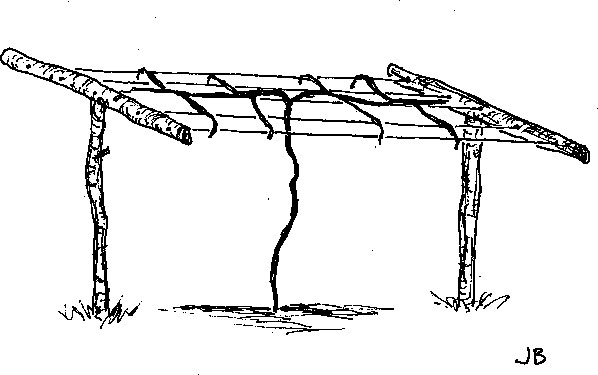

| Kiwi trellis. Illustration by John Bunker. |

Hardy kiwis also require a lot of water. Young plants should be watered three or four times per week unless ample rain is falling. Water deeply at a rate of 3 to 4 gallons per square foot of root area. Mature plants should be watered once a week. Actinidia arguta vines are extremely vigorous, reaching 50 to 100 feet in the wild. Actinidia kolomitka reaches 15 to 20 feet. A sturdy arbor, trellis, fence, or porch screen is necessary for support. Allow 150 square feet per plant on overhead trellises. Typical arbor spacing for individually maintained and pruned plants, is 15 to 20 feet between plants and 15 feet between rows. A trellis or simple cordon system, similar to that used with grapes, works well.

As male plants are less hardy, yet essential to fruit set, special attention should be given to their site. Consider planting males in your most sheltered spot or on the edge of the woods, if those spots are within pollination range of the female plants. The forest edge can provide added protection, while allowing the vine to climb in the trees. Only the females need to be pruned and accessible for fruit harvest.

Vines can grow satisfactorily with little pruning, but as fruit are borne on new growth on the previous year’s canes, yields can be greatly increased with pruning. Even the non-specific lopping of estate vines kept them manageable, blooming and producing fruit. The basic principles of pruning grapes apply to hardy kiwis. A T-trellis is required to support the heavy vine and fruit load. Train each vine to a stake and allow it to grow up until it reaches the central top wire of the trellis. Prune off any laterals that grow from this central trunk. In cold areas, consider maintaining a second trunk in case of winter kill.

Prune off the tip of the trunk and train two branches to grow in opposite directions on the central wire. These are your main leaders, which, along with the trunk, are the permanent structure. Over the next few years, side branches will form. These emerging laterals will bear the fruit. Buds closest to the trunk with less than 2″ between nodes will bear the most fruit. Train these branches so that they grow to the outside wires and hang down. These laterals should be spaced 10 to 15 inches apart. During the dormant season, cut them back to eight to 13 buds.This stimulates the growth of fruit buds. The cane will then fruit for two years. During each dormant season, cut the cane back to eight to 13 buds to encourage the growth of new fruiting wood. Every three years, prune off up to 60 percent of the existing side branch vegetation. This encourages new growth of fruiting wood. Any new shoots coming from the base of the plant should be pruned off.

Neglected plants should be brought back to a manageable form over a few years. Prune off old wood, create new main arms if needed, and encourage new growth.

Harvest

Plants start to bear by their fourth or fifth year, depending on growth, taking up to eight years to reach peak production. Fruit ripen in September and can be picked by hand or from the ground after they fall. (Don’t pick up any fruit that has been in contact with manure, however.) Several pickings are usually needed. Undamaged fruit can be stored for three to four months. Yields from mature vines can be upwards of 100 pounds per vine. In harsh climates, expect as little as 20 pounds per vine.

Recommended varieties include the following females: Michigan State, Meader #l, Ananasnaja (Anna), Geneva #l and #2, or any local plants. For males, few are named. Seek the most northerly source and ask where the parent plant is located.

Sources

O’Donal’s Nursery in Gorham, Maine

Skillin’s Nursery in Falmouth, Maine

Tripple Brook Farm, 37 Middle Rd., Southampton, Mass. 01073 (mail order); Phone (413) 527-4626

Fedco Trees, P.O. Box 520, Waterville. Maine 04903 (available in 1999)

Bibliography

Actinidia Enthusiasts’ Newsletter, #2, April 1985

Ferris, Lloyd, “Down to Earth,” Maine Sunday Telegram, Sept. 7, 1997

Fulford, Mark, Teltane Farm Nursery Catalog, 1992-1993

Hill, Lewis, Fruits and Berries for the Home Garden, Storey Communications, 1992

Lock, Ward, D. Coombs, P.B. Maze, M. Cracknell and R. Bentley, The Complete Book of Pruning, 1994

Otto, Stella, The Backyard Berry Book, Ottographics, 1995

Reich, Lee, Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention, Addison-Wesley, 1991

Smith, Miranda, Backyard Fruits and Berries, Rodale Press, 1994

Tripple Brook Farm 1990 Plant Catalog

Wagner, Bob, “Hardy Kiwifruit,” The Natural Farmer, Winter 1983