|

| With attention to variety, siting and soil, many varieties of grapes can be grown in northern New England. Photo by Dierdre Fuchs. |

By John Fuchs

Grapes are an ideal, but often challenging, crop for the homeowner or homesteader to grow in far northern climates. They are amazingly productive, grow in a wide variety of soils and need surprisingly little care. Their basic requirements are full sun and as little exposure to chilling north winds as possible. Space them 10 to 12 feet apart. Once established and properly pruned, self-pollinating grape vines will yield excellent crops for 25 years or more.

Soil that is adequate for vegetables will be fine for grapes. If the selected site has been worked for a few years, deep-rooted weeds will be less troublesome. Although not absolutely essential, preparing the soil the fall before planting is a good idea. Incorporate well rotted compost and rock phosphate (if your soil needs P) into the plot in October; and if the soil pH is below 5.5 to 6.5, add lime.

While grapes tend to do better in well-drained soils, they will grow in heavy soils. By supplying a mixture of equal parts of peat moss, dried cow manure and garden soil to the planting hole, you’ll ensure that the vine gets off to a good start. Mulch the vines with hay, and add compost annually to maintain soil fertility. Avoid large additions of nitrogen (possible if grass clippings are used for mulch), which can produce excess vine growth and winter injury.

Grapes tolerate a range of temperatures and precipitation. Varieties are available that will grow in hot, dry areas as well as in cool, moist ones. Aside from the need to keep the soil moist after planting, you won’t need to water grape vines unless we have a prolonged drought. Indeed, one grower told me he had not watered his grapes in the past two years, and yield had not suffered. (He mulches heavily.)

While grapes benefit from a deep mulch, growers in New England have learned that they can lengthen their season by a week or more by pulling back the mulch cover in early spring. Mulch slows the warming of the soil, and grape vines will not grow until their roots are warmed. While the mulch is pulled back, a bushel of well rotted manure can be applied. By mid-June, the mulch can be raked back onto the vine roots.

Another virtue of backyard grapes is that they are seldom troubled by pests or diseases. Birds can be a problem but can be discouraged by placing paper bags over the grape clusters as they ripen.

Varieties and Strategies for New England

Grapes grown in the eastern United States generally are of the species Labrusca. These vines are hardier and require shorter ripening periods than the other two common species of grapes. The most prominent of the eastern grapes is the ‘Concord.’ Hardy to -15 F., this variety is popular because it can be used for juice, dessert, wine and jelly, and, like most Labruscas, the skin slips off easily and the grapes grow in fairly large bunches. While ‘Concord’ is fine for southern and central New England, as are ‘Catawba’ and ‘Vanessa,’ the fact that it takes 150+ days to bear makes it iffy for northern New England; and, according to John Bunker of Fedco Trees, it almost certainly will not ripen in central Maine.

In recent years several new varieties that are hardy to -20 F. and mature 20 to 30 days before ‘Concord’ have become popular with northern New England growers. ‘Fredonia,’ ripening in early September, produces blue-black fruit that is larger than that of ‘Concord’ and is produced in large, compact clusters. Its spiciness makes it desirable for jellies, juice and wine. ‘Bluebell’ is even earlier than ‘Fredonia,’ with similar fruit, more hardiness and some disease resistance.

A hardy red seedless type that has done well in the north is ‘Reliance.’ ‘Edelweiss,’ developed by the University of Minnesota specifically for growers in zone 4, is a hardy, vigorous producer of table quality white grapes. It makes a nice, dry white wine and, best of all, ripens in mid- to late August.

Other hardy varieties that are quite suitable for central and northern Maine are listed in the Fedco Trees catalog (https://fedcoseeds.com/trees.htm), and new varieties are being introduced nearly every year, most from Minnesota and certainly hardy and early enough for Maine.

Pruning

Left to their own devices, grape vines will quickly envelop a back yard, with tendrils wrapping around anything in their path. To conserve space, for aesthetics and to greatly enhance production, growers should learn to prune grape vines. It is no exaggeration to say that a properly pruned, mature grape vine will produce four times as much fruit in a quarter of the space as an unpruned vine.

Pruning should begin at planting. Many nurseries prune vines before selling them. If this has not been done, do it yourself. Drastic pruning at planting encourages roots to grow faster than the top and will spur earlier, heavier crops. Begin by cutting off two-thirds of the top. Then prune off all the side branches and cut back the stem so that it is less than 6 inches tall. This initial pruning strengthens the plant by reducing the roots’ burden.

Grapes grow almost entirely on one-year-old wood. Your goal should be to allow the canes to grow one year and bear fruit the next, then you should remove them. This means that each summer your plant should have canes at two stages of growth: canes that grew the previous year and are now bearing fruit, and new canes that will bear fruit next year. In addition, you should prune off some of the fruit-bearing canes to keep the vine manageable. Most gardeners find it particularly difficult to cut back fruit-bearing canes. The thought of lopping off vines that produce fruit seems wasteful – even sinful to some. In the long run, however, such pruning will enhance the quality of grape production by permitting the sun to get in and ripen the fruits, and it will help the vine prosper by cutting down the distance the sap has to travel to produce grapes.

|

|

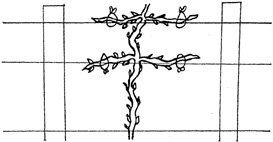

| Grapes should be pruned to a single cane the first winter; eventually four vines are trained to two wires. Illustrations by John Fuchs. |

To encourage people to overcome the fear of taking off too much, I recommend the Kniffen system of grape care. In addition to providing a step-by-step guide for yearly pruning, the Kniffen system is well suited to areas where cloudy, moist conditions can occur even in midsummer (i.e., New England). The Kniffen system allows for good air circulation and the light necessary to ripen grapes and prevent fungal diseases. It is also inexpensive and easy to set up.

In the Kniffen system, grapes are trained to grow on two strands of 10-gauge wire stapled on posts spaced 8 to 10 feet apart. The lower wire is roughly 2 to 3 feet above the ground, and the second is about 5 feet from the ground.

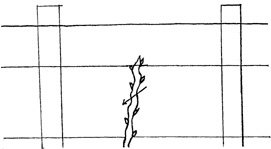

During the first winter, at planting time, prune the vine to a single cane and tie it to the bottom wire. Always use soft twine and tie it loosely. If the cane does not reach that high, prune it to three buds. (Illustration 1)

During the second winter, prune the main stem to 6 feet tall and tie it to the wire. Leave four to six buds near each wire.

In the third year, tie two canes to each wire, going in opposite directions, for a total of four producing canes growing on two parallel wires. Cut these canes back to 10 to 15 buds each. Leave four more canes on the main stem, and prune these back to two buds each. These vines will replace this year’s producers next year. Allow them to droop on the ground during the summer.

The year-old vines attached to the wire should bloom and set grapes. In the winter, remove the old vines and fasten the new ones to the wires. Repeat this process every year.

Always prune grape vines when they are dormant and always use a sharp hand pruner. Clean, even cuts lessen the chance of disease. A 6-inch-long pruner is all you need if you adhere to the Kniffen system. If, however, things get out of hand, you’ll need a pruning saw to do the heavy work. A double saw – with coarse teeth on one side for big wood and fine teeth on the other for smooth work – is ideal for an overgrown vine. Jagged cuts made by the coarse teeth can be evened off with the fine teeth.

John Bunker of Fedco trees emphasizes that “vines absolutely MUST be pruned every year. You can easily and safely prune off nearly 90% of all growth every year.”

Yields

Yields from a grape vine vary according to variety, soil and climate. A properly pruned grape vine should produce 30 to 60 bunches per season by the fourth year. If you employ the Kniffen system, you should set 15 bunches per branch (60, total) as your maximum production. Overproduction will eventually weaken the vine, and the quantity and quality of fruit will diminish over time.

If, by the fourth year, your yield is less than 30 bunches per vine, an application of bonemeal may be warranted. To avoid cutting the roots of the vine, apply the fertilizer in a circular band 18 inches from the base of the vine. Use a spade to lightly work the bonemeal into the soil.

In the far north, some canes may experience winter injury in some, if not most, years. Prune out any canes that are dead along with those that fruited last year. To check for winter injury, scrape the back of the one-year-old canes and look for the green tissue that should lie just underneath. If the tissue has turned brown or gray with no green, the cane has probably been injured. You can also check the buds for injury by cutting across a bud and looking at the cross section. The center layers of the bud should be light green or yellow. If they are brown or black, some damage has occurred and yields are likely to be reduced.

The beauty of grape growing is that the grower is abundantly rewarded for a small amount of work. Grape vines provide nourishment and beauty for the homeowner. For the small market gardener, grapes provide an interesting crop late in the season. As one southern Vermont grower told me, “Grapes really draw customers to my table. Locally grown, organic fruit is big around here.”

For more information, see www.newenglandwinegrapes.org/ and

https://learningstore.uwex.edu/pdf/A1656.pdf.

Thanks to David Handley of the University of Maine Cooperative Extension and to John Bunker of Fedco Trees for contributing to this article.

About the author: John Fuchs is a Master Gardener and writer who lives in Bellows Falls, Vermont.