By Noah Gleason-Hart

If thoughtful forest stewardship is a long, winding road, then a forest management plan (FMP) is the map that can lead to a healthy, complex and productive forest. These documents – written by licensed foresters – describe the current state of a forest, define the landowner’s objectives and prescribe actions a landowner can take to steer a forest towards their goals. FMPs are the foundation of long-term management, and I would encourage all forested landowners to have one written. If you decide to have a plan written, what does the process look like and how can you ensure that your plan helps you meet your goals?

In 2020, MOFGA updated the management plan for our 125-acre forest in Unity: understanding how we navigated this process may be useful for folks considering a plan for their own woods. MOFGA’s foresters, Barrie Brusila and Maren Granstrom from Mid-Maine Forestry in Warren, Maine, graciously agreed to chat with me and share their experience working with landowners and writing plans.

According to Brusila, a management plan is useful as, “both an educational tool and an operational tool for your property.” As an educational tool, it provides you with information about the quality and value of your trees, assesses ecosystem health and identifies wildlife habitat, among other information. “Sometimes people are … overwhelmed by the idea of owning land and wonder where they should start and what’s most important,” says Brusila. “A plan will help you set priorities and help you determine what could be done and what should be done during the 10-year life of the plan.”

Determining Your Objectives

Clearly defining your objectives is key to creating a management plan that you will actively return to for guidance in the future. There are as many management objectives as there are landowners, and it is common to have several primary goals for your woodlot. The options are endless, though one role your forester has in writing the plan is to reconcile your goals to the constraints of natural systems and the current conditions of your woodlot. You may need to lengthen your timeline if, for example, you would like to grow high-quality wood products but your forest is currently very young.

A glimpse of MOFGA’s woodlot 10 years after a harvest prescribed in MOFGA’s previous management plan. Gleason-Hart photo

Brusila also stressed that a forest management plan is a useful document even if your objectives do not include the production of forest products. She noted that the main objective of most of the property owners she works with is to increase forest health, and her clients are often surprised to discover that using harvesting to create thoughtful disturbances can increase species and age diversity, wildlife and climate resilience. You don’t have to harvest just because you have a management plan – and we need passively managed reserves – but I would also encourage you to consider how careful logging might help you reach your non-timber goals.

In MOFGA’s case, the process of updating our management plan provided an opportunity to step back and reflect on the past 20 years of work and intentionally consider our goals for the next decade. To better understand the views of various stakeholders, in the winter of 2019 to 2020, we surveyed MOFGA staff and low-impact forestry (LIF) steering committee members, asking them to rank potential management options to identify how the Unity forest was essential to them.

The results of the survey were enlightening. They reaffirmed our commitment to some of our objectives, like a central focus on education and lumber production for MOFGA’s use, but also made clear that some of the goals of previous management work, like selling logs to outside mills, may not be as important as they were in the past. Finally, the survey revealed that in the past decade entirely new objectives – like increasing the carbon-sequestering capacity of our forest – had become essential considerations for our community.

Though your deliberation process may not include an online survey and large meetings, I would encourage you to bring together all the stakeholders of your land – whether that includes children, a partner or co-owners – to discuss your objectives for your woods.

Find the Right Forester

Once you’ve decided to have a plan written and thought a little about your objectives, your next step is to find a licensed forester to assist you. According to Granstrom, a great first contact when looking for a forester is your local district forester from the Maine Forest Service. Though these state employees can’t write a plan for you, they can answer your initial questions, may be able to walk your property with you and can provide you with a list of foresters in your area – all free of charge.

Once you’ve identified a shorter list of foresters you feel could be a good fit, reach out to each of them. Some foresters allow potential clients to read a sample management plan they’ve written – with the original plan owner’s permission – or you can interview them and/or talk with friends and neighbors who have worked with them before.

It pays to take your time choosing a forester. When asked what she would recommend in looking for a forester, the theme Brusila returned to several times was trust. She likened the process to building a relationship with any other professional, like a doctor or an attorney. “It’s important to choose somebody you feel comfortable working with,” says Brusila, “because hopefully, it will be a long-term relationship.” You should find someone who shares and understands your objectives and isn’t going to push their own ideas, says Brusila.

At MOFGA, we wanted to work with a forester who demonstrated a commitment to LIF management, a willingness to engage with our participatory decision-making process and experience working with – and marking harvests for – the types of equipment MOFGA prefers to use, like draft horses and forwarders. The requirements you have of a forester may differ from ours, but it is essential that you find the right person. As in MOFGA’s case, it can be a relationship that spans decades.

Funding Opportunities

Management plans that comprehensively outline the on-the-ground conditions of your woodlot and accurately reflect your objectives are a significant investment. However, landowners can access several voluntary programs to offset some or all of the cost of a new or updated plan. Two of the most commonly used are WoodsWISE Incentives from the Maine Forest Service (MFS) and cost-share funding from the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS).

Each program has specific requirements about the types of information that must be included in the plan; NRCS plans contain more information, which may or may not be helpful depending on your objectives and the size of your property. Some landowners would prefer not to participate in government programs and paying out-of-pocket for a plan is certainly an option.

If you do apply for NRCS or MFS funding, note that both programs maintain lists of foresters approved to write plans for them, so be sure that any forester you’re interested in hiring can work under the funding you are pursuing.

MOFGA chose to apply for NRCS funding. In addition to reimbursing MOFGA for the total cost of the initial plan, having a plan written to NRCS specifications will allow us to apply for other NRCS forest cost-share programs to cover some of the costs of implementing our new plan.

Keep in mind, the NRCS application process can take time. It took more than a year and a half from the moment MOFGA submitted our application to the time we had our new plan, which may be a barrier for some landowners.

Data Collection and Plan Implementation

Regardless of whether you’ve hired a forester to write you a simple plan or a comprehensive NRCS-funded plan, your forester will come out to walk your property to understand current conditions and gain a better sense of the management options a landowner asks for and, if a funding program like the NRCS requires it, a complete inventory.

Think of it like an inventory in a store, says Brusila, but the difference, according to Granstrom, is that a forester can’t count or assess all of the individual trees in a forest. There are just too many trees to make that feasible. Foresters can estimate tree volumes, values and the species composition of a forest by using sampling methodologies with clearly defined margins of error.

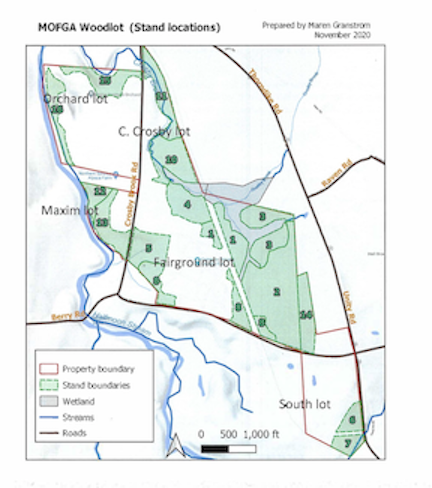

A map of the woodlot at the Common Ground Education Center in Unity, excerpted from MOFGA’s new 10-year forest management plan prepared by Barrie Brusila and Maren Granstrom of Mid-Maine Forestry.

After completing their fieldwork, your forester will draw or create maps of your property, divide the lot into “stands” (multi-acre groups of trees similar enough to be managed in the same way) and describe the current conditions of those stands. The plan will lay out your management objectives and make a stand-by-stand plan recommendation for action. These recommendations are summarized in a table of suggested management activities that you can easily reference as you begin implementing your plan.

MOFGA received our new 10-year management plan this January, which you can read in its entirety on mofga.org. Granstrom and Brusila have recommended that over the next decade we carefully thin more than 30 acres to increase forest quality and productivity and mechanically control 12 acres of non-native plants to ensure continued ecosystem function. We are excited to have our next steps so clearly laid out and are committed to carrying out this work in a way that demonstrates that LIF management is an ecologically and financially sustainable option for woodland owners, stewards and loggers. Because we have a management plan in place, we know both where we want to go and how we will get there. Stay tuned.

If you are interested in becoming involved in MOFGA’s forest management efforts in Unity, consider attending LIF’s bi-monthly steering committee meeting. Please reach out to Noah Gleason-Hart, MOFGA’s low-impact forestry specialist, at [email protected] for more information.