By Eric Sideman, Ph.D., MOFGA’s Director of Technical Services

Wheeling great quantities of potatoes or lugging boxes of squash to their winter storage site gives the greatest sense of self sufficiency and satisfaction to gardeners. Going down to get a bit for dinner on a January night and having to sift through a mass of rotting food gives a horrible sense of failure. Some friends of mine have given up the satisfaction of producing enough to store as their way of avoiding that sense of failure. I hope this information on the most common problems of a few storage vegetables gets them back into providing their own food after the ground freezes here in Maine.

|

| Black rot on a pumpkin |

Black Rot of Squash

Black rot is the most common and serious problem for those storing winter squash. It is caused by a fungus called Didymella bryoniae. In winter squash the symptoms may be seen in the field before harvest but are commonly overlooked until the fruit begins to rot in storage. On butternut a superficial, tan to white, petrified area may develop in distinct concentric rings and may be seen when the fruit is immature. More commonly, a brownish pink, water soaked area develops on areas where the fruit may have been damaged during harvest. This develops into blackened areas that wrinkle and shrink over time in storage.

This disease is actually a continuation of a disease called gummy stem blight that occurs during the growing season. Circular, tan to dark brown spots appear on the leaves, often first at the margins, then they enlarge until the entire leaf is blighted. Later, stem cankers develop. The pathogen survives between seasons on diseased vines and crop debris and may be seedborne. Leaf wetness is a major factor in spore production and expansion of the lesions. Fruit may be infected through wounds or through scars that occur when flower parts adhere to the developing fruit.

Control of the fruit rot begins by controlling gummy stem blight. A two-year crop rotation is the best approach for organic growers. Avoid using compost with squash debris in it unless your compost pile gets hot and kills the pathogen. Be sure you use disease-free seed. Take special care to avoid rind injuries during harvest. Curing helps any wounded areas heal themselves by producing corky tissue. After harvest, cure squash at about 75 degrees for about two weeks, then store it at about 50 degrees in a dry place.

Blue Mold of Garlic

Blue mold is also a disease of onions and may be seen on growing garlic, but it is most commonly seen in garlic during storage. It is caused by one of several species of the Penicillium fungi. The first symptom is a pale yellowish blemish that may appear watery. Later, greenish blue mold develops on the lesion and spreads to the surface.

Penicillium grows commonly in the soil and on plant and animal debris. Invasion is usually through wounds, but unwounded garlic may also be infected. Once inside the tissue, the fungus ramifies through the fleshy scales, and spores are produced on the surface. Entire cloves of garlic may become masses of blue spores.

The best control is to prevent other diseases and wounding of garlic. After harvest, garlic should be dried quickly in a warm place out of the sun (this happened back in August here in Maine) and then stored in a cold (but not below 32 degrees), dry place over the winter.

|

| Neck rot on onion |

Neck Rot of Onion

Neck rot is primarily a storage problem of onions. It is caused by the fungus Botrytis allii. Infection occurs when bulbs are harvested and placed in storage. The rot begins in the neck area and gradually moves downward through the entire bulb. The scales soften and become water-soaked and translucent. A white to gray mold may grow between the scales, and sclerotia (a mass of fungal hyphae) may form on the outer scales.

The organism overwinters as sclerotia on rotting bulbs or free in the soil. The sclerotia produce spores in the spring, and leaf tissue may become infected then but will show no symptoms. The fungus growing during the summer produces spores, and if the necks of onions are still succulent at harvest, they provide an entry point for infecting the bulb. The fungus is unable to penetrate well-dried neck tissue, thus bulbs with dry, tight necks do not get infected.

Practices that hasten curing are the best control for neck rot. Undercutting bulbs at maturity to sever all the roots helps in seasons where onion growth continues late. If the necks are not curing well in the field and it is getting late, harvest the onions and place them upside down – on pallets, for instance – with the leaves hanging down. Allow the onions to cure and dry for several weeks until the skins are papery and the roots are completely shriveled and dry. Then, store onions in a cold (but not below 32-degree), dry place.

Fusarium Dry Rot of Potato

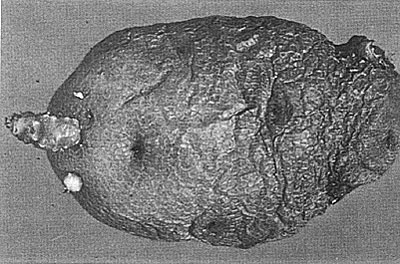

|

| Fusarium dry rot of potato |

This is a common problem of stored and seed potatoes. After about a month in storage, lesions at wounds in the potato are visible as small brown areas. The infection slowly enlarges, and the surface sinks and wrinkles. Rotted tubers shrivel and become mummified. Internally the potato turns shades of brown. Older, dead tissue may become dry and punky in texture. Also, a secondary infection by the bacterium Erwinia is common, and the potato rapidly rots and smells. Bacteria in the leaking juices from the original infected potato can endanger surrounding tubers.

Fusarium cannot infect intact tubers. Wounds from harvesting or storage, or from insect and rodent feeding, are the entry points. The pathogen can survive for several years in the soil without a host, but the primary inoculum is generally borne on the seed pieces. Infected seed tubers infest the soil, then that soil adheres to harvested potatoes and infects the tuber if it is wounded.

Tubers tolerate infection when harvested. Susceptibility increases during storage and reaches its maximum in the spring. Control of Fusarium dry rot starts at harvest by avoiding damage to the potato. Harvest your storage potatoes from dead vines because this does not leave a scar and because late blight spores die with the vine and will not infect the tuber. Providing high humidity and good ventilation early in the storage period facilitates wound healing, which can reduce infection. Cure potatoes at 45 to 60 degrees with high humidity in darkness for about two weeks. After this period the optimum temperature for storage is 40 degrees with high humidity. Lower temperatures will turn the starch to sugar and encourage sprouting. Higher temperatures encourage sprouting too.

About the author: Eric is available to answer your questions about farming and gardening. You can call him at the MOFGA office. Look for him at the Common Ground Country Fair, too.