|

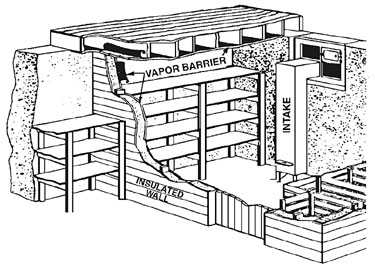

| Illustration courtesy of University of Alaska Fairbanks. |

by Cheryl Wixson

Root-cellaring is a saving technique for ordinary winter storage of fresh, raw, whole vegetables and fruits that have not been processed to increase their keeping quality. The root cellar is a way to hold these foods for several months after their normal harvest in a cold, rather moist environment that does not allow them to freeze or to complete their natural cycle to decomposition in the fall.

Many Advantages

Root-cellaring your fruits and vegetables has many advantages. First, having a winter’s supply of food put by provides an immense feeling of security. So what if they blow up the bridge in Kittery, you’ll still have enough to eat! Root cellars help conserve energy, as the food that you enjoy all winter has not traveled thousands of miles to get to your plate. Root cellars can save money: Crops that you grow or obtain locally at the peak of harvest are more economical than those purchased in December in the supermarket. Root-cellaring is also an alternative to investing in additional freezers or canning supplies.

Perhaps what my family enjoys most about the root cellar is the whole new system of eating that it fosters: Local, Seasonal, Organic (LSO), an age-old system based on the seasons. Research indicates that foods enjoyed in season have health benefits also. In the fall and winter, the beta-carotene, antioxidants and phytochemicals in squashes, carrots and other roots give our bodies extra defenses to fight colds, and the complex carbohydrates of root vegetables help us maintain high energy levels during the coldest months.

As spring becomes summer, we enjoy more leafy greens and salads, giving our bodies additional water and such minerals as iron, potassium and phosphorus. We look forward to our asparagus in May and peas in June, knowing that a full year will pass before we eat them again. The last winter apples are eaten just before the strawberries, raspberries and blueberries start to ripen. We feast on endless summer squash and zucchini baked in muffins and breads, grilled or stir-fried, and in salads. Our eating follows a pattern – what’s fresh, what’s local, what’s in season – a pattern complemented by root-cellaring.

The Right Space

Unfortunately, of all the time-tested ways of putting food by, root-cellaring is less satisfactory than it was a century or more ago due to technological advances in home construction. Traditionally, root cellars were underground in the cool, damp cellar of the farmhouse, with dirt floors and stone or brick walls. Today’s homes, with finished basements with concrete floors and centralized heating systems, do not provide optimum conditions for long-term storage of produce without some modifications. However, with a little research and understanding of the science of storing produce, almost any space can be adapted for root-cellaring.

The two basic requirements for successfully storing produce in root cellars are the proper temperature and humidity. In their excellent book Root Cellaring: Natural Cold Storage of Fruits and Vegetables, Mike and Nancy Bubel detail construction of several types of cold storage, from trenches, “keeping closets” and bulkhead storage to specific rooms built in finished basements. Particular vegetables and fruits have specific temperature and humidity requirements.

Foods that like cold temperatures (32 to 40 degrees F.) and high humidity (90 to 95% relative humidity) include beets, carrots, parsnips, turnips, celery, winter radishes (Daikon), leeks and Jerusalem artichokes. Potatoes, cabbage and apples also do best at 32 to 40 degrees F. but with less humidity (80 to 90% relative humidity). Garlic and onions keep best in cool temperatures, 32 to 50 degrees F., and dry conditions, 50 to 60% relative humidity. Pumpkins, winter squash and sweet potatoes store ideally with a moderately warm temperature (50 to 60 degrees F.) and dry conditions.

At first, this may seem complex, but with experience you will be able to locate a storage place for all. First, visit your local hardware store and invest in a good thermometer and hygrometer. Using your thermometer, find the coldest place in your house or basement that is most suitable for your root cellar. As the Bubels write, a good root cellar can both “borrow and store cold.” To borrow cold, you can dig deep into the earth, or during the fall and spring, you can allow colder, outside night air in to cool the cellar by opening a window, using a louvered vent or running a fan. Storing the cold usually requires some type of insulation.

In addition to a thermometer and hygrometer, you’ll need tubs with lids, crates, straw, sand or wood shavings. More sophisticated root cellars may have fans or ventilators.

Other resources that can help you construct a root cellar include Stocking Up (Rodale Press). Its excellent chapter on Underground Storage recommends constructing an 8- by 10-foot room in your finished basement, probably in the northeast corner, and farthest from the boiler. The book also has construction details for concrete storage rooms, soil pits, mound storage, hay bale storage, pit storage and even a truck body located underground.

Putting Food By by Ruth Hertzberg et al. (Stephen Greene Press) also devotes a chapter to root-cellaring, as does Preserving Food without Freezing or Canning by the gardeners and farmers of Terre Vivante in France. The forward, The Poetry of Food, crafted by Eliot Coleman, inspires us to eat “real food.” These books are good additions to the home library, as they also have recipes and ideas on how to enjoy the fruits of your storage. The Cooperative Extension Services of many universities, including Purdue, Colorado State, the University of New Hampshire and University of Alaska, Fairbanks, have Web-based information about root-cellaring.

Bulkhead Bounty

My first root cellar was in the bulkhead of our 1929 bungalow in Bangor. Our home had an existing space that the former owners had used as a root cellar, complete with wooden storage bins and closets for canned goods, but the temperatures were rarely below 50 degrees. My husband converted that to a wine cellar, and we used the steps going from the cellar to the outside for a root cellar. My husband insulated the top of the bulkhead door with sheets of rigid insulation, and I tracked the temperature with a thermometer. When the forecast called for temperatures below zero, we could maintain the temperature around 32 degrees by cracking open the door from the bulkhead to the heated portion of the cellar.

I stored apples in tubs on the top steps. Of all my produce, apples could withstand the coldest temperatures and still be suitable for eating. Use caution when storing apples, however: They give off ethylene gas, which promotes ripening and maturation of other vegetables and, at some concentrations, can promote sprouting in potatoes. A farmer friend ruined his whole crop of carrots by storing them with apples. By using tubs with lids, the gas stays in the tubs, as does the condensation.

We hung mesh bags of onions and garlic from hooks in the front, closest to the heated part of the basement. Potatoes were stored in paper bags and leeks in sand in open plastic tubs. I must confess that I don’t harvest my leeks until the January thaw. Last winter the snow cover made finding them a bit more challenging!

Beets, carrots, turnips, celeriac and winter radishes like very humid conditions, and store best packed in moist sand or wood shavings. Last winter I was fortunate to find winter pears in early December, and stored them in a wooden crate toward the front, enjoying them into late January. I wrapped my cabbages in newspaper and set them on the steps. They can be quite odiferous, and some folks choose to store them in a separate location.

Pumpkins and winter squash prefer warmer and drier conditions. We store butternut and ‘Delicata’ squash in an unheated bedroom. My ‘Delicata’ usually keep until April, and I still (in late July) had one butternut that I was hoarding for a special occasion.

This arrangement served us well from November into early April. By then, most of our produce was depleted, and the remainder could be moved into a second refrigerator that we kept in the basement specifically for storing root crops.

Check Frequently!

Only fresh and sound produce should be root-cellared. The food should be free from cuts, cracks, bruises, insects and mechanical damage. When I prepare produce for winter storage, I inspect it carefully. Items with any damage are either eaten quickly or canned or frozen. Apples and pears can be made into sauce, squash roasted and frozen, and beets pickled.

Visit and inspect your root cellar frequently. The old adage that one bad apple rots the barrel is true! I visit my root cellar every few days, enjoying the satisfaction of having plenty to eat without traveling to the supermarket. Basket in hand, I carefully check my apples, selecting any that show the first signs of softening or rot. Some go into the nightly salad, some are eaten out of hand, and if there are enough, some are baked into a crisp or pie. I select potatoes, carrots and other vegetables for the next few meals, taking comfort in the thought that my food supply is safe and secure.

I highly recommend keeping a journal. I use my journal to track outside temperatures and compare them with root cellar temperatures. I also record the condition of my produce through the winter, what I prepare with the food, recipe ideas and storage tips. This information is invaluable for planning for the next season. Here are two examples from my journal:

January 9, 2008: another warm day, root cellar 45 degrees. Sorted apples and pears. Harvested leeks. Dug snow. Ground not frozen. Some pears had frozen (from minus 5 degrees cold snap earlier in the week). Made pear sauce. Apples fine, especially Belle de Boskeep! One delicata and 1 butternut with small spots of rot. Roasted for supper.

February 21, 2008: Red Cabbage Slaw: chopped red cabbage, red delicious apple, grated Daikon, wheat berries, pecans, dressing maple syrup, raspberry vinegar, olive oil, cranberry jelly. Excellent keeper!

Quantities and Varieties

Perhaps the biggest question regarding root-cellaring is how much food you’ll need. If your family is unaccustomed to the joys of the LSO diet, I recommend starting small – perhaps with a second refrigerator in the garage or basement. If your family is more adventurous and eager to commit to eating the way our great, great grandparents did, you might start with these quantities for a family of four:

Apples: 5 bushels

Carrots: 40 to 60 pounds

Cabbage: green, 20 heads; red, 10 heads

Beets: 20 pounds

Celeriac: (celery root, use instead of celery) 10 to 20 heads

Leeks: 40 plants

Potatoes: 100 pounds or more

Jerusalem artichoke: 10 pounds

Onions: 40 pounds

Garlic: 10 to 20 pounds

Winter radish: 10

Parsnip: 20 pounds

Squash: 40 ‘Delicata’ and 30 pounds butternut

Pumpkin: 5 to 10

Turnip and rutabaga: 10 or more

Certain varieties of vegetables keep better than others. ‘Bolero,’ ‘Purple Haze’ and ‘Chantenay’ carrots are good storage crops, while ‘Mokum’ and ‘Napoli’ are better harvested and eaten fresh. Seed catalogs such as Fedco and Johnny’s have variety information, and the Bubels devote a chapter to Good Keepers.

Local farmers are also excellent resources. They provide food for their families all winter and can give you storage tips, cooking suggestions, even recipe ideas. I am constantly amazed at the breadth of knowledge and common sense of our farmers. Many also offer root crops for purchase throughout the winter.

Accepting the challenge of storing your family’s food for the winter and getting off the corporate food train is not easy and requires diligence and commitment, but the opportunity to eat real food, to know where your food comes from, to be secure in knowing that you can provide for your family is a huge step toward food independence. I encourage you to nourish your bodies and your souls, and enjoy the fruits of your labor. Happy eating!

Cheryl Wixson is MOFGA’s resident chef and Organic Marketing consultant. She and her husband of 33 years recently moved to Stonington and are designing their new root and wine cellars. Cheryl welcomes your questions, comments and observations. Contact her at [email protected] or 207-852-0899.