|

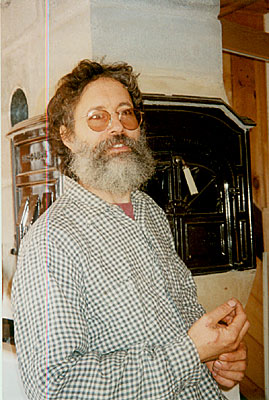

| Don McLean beside his bread oven. Photo by Joyce White. |

By Joyce White

Don McLean has been an environmentalist much longer than he has been a veterinarian. In third grade, he did his science project on pollution. “Since then I have been trying to at least reduce the negative impact of modern life on our environment,” he said recently at his solar home-in-progress in Norway, Maine.

McLean, who grew up in Oregon without much money, has had “a lot of experience in not wasting, in doing without, in using up whatever you have and in planning ahead.” That attitude appears to inform his approach to every facet of his life.

Earth Day (April 1970) focused his awareness on what we’re doing to the environment and what we can do to improve it so that we can leave a livable environment for future generations, he says. When living on the Umqua River in Oregon, he and a friend decided to protest the releasing of raw sewage into the river whenever the electricity failed. From their desire to change awareness in a positive way, they started a river appreciation group.

He worked on farms and forest lands as a tree planter and observed clear cuts close up. “As my awareness grew of how corporations and government agencies operate, I saw that they don’t always have people’s best interests at heart,” he says. “America is good at marketing stuff, at getting people to want more stuff no matter how much you already have. Quality of life often seems not to be a high priority for them, but if you can’t drink the water, can’t breathe the air and if the soil is toxic, what good is that?”

In Oregon he found mentors for a simpler lifestyle among some of the older people, especially in Mary Rogers, “a subsistence farmer who taught me a lot about how to live.” And he has found that kind of help from older people in Maine. “Maine has been good to me. A lot about Maine reminds me of how Oregon used to be.”

He found support for his efforts to create a satisfying life in keeping with his ideals of simplicity and non-exploitation from Living the Good Life authors Helen and Scott Nearing as well as from Mother Earth News and Organic Gardening magazines.

“I bought my first photovoltaic cell from a comic book for $2.75 in 1972,” he says. Since then, McLean has studied and experimented with several forms of alternative energy. In an early experiment in biogas production, he built the plant in his high school shop and was able to run a lawn mower and cook a few meals with the gas from the plant. Prior to that, he had built his first biogas plant, which used chicken manure, in his bedroom. His parents ended that experiment abruptly following an unfortunate rupture of a pipe carrying the manure.

|

| McLean with his photovoltaic system. Photo by Joyce White. |

In the solar powered home he is building, McLean has used recycled, surplus and local materials as much as possible. Beams came from a house he and a friend dismantled. The chimney was constructed from discarded industrial materials. A bread oven, inserted into the chimney on the first floor, was rebuilt from a cast off, cast iron stove. The source of heat is the wood stove in the cellar, but he said he can also add a grate and make a fire directly in the bread oven.

The donated cook stove in the kitchen area is a model of efficiency, featuring a wood burning area on the right side and gas burners on the left. The hot water tank, located in a cupola reached from the second floor, is heated by the sun from flat plate solar panels, with help from the basement wood stove on sunless days in winter. He described it as a thermal siphon water heater: When the wood stove is being used, cold water goes down the pipe and hot water is forced up so that no pump or electricity is used.

When the batteries are full, an internal switch flips on and directs the extra power into the water heater. He sees the batteries as the weak point in the system, because they’re expensive, they’re heavy and have limited capacity. They eventually wear out, but McLean’s batteries are from 25 to 32 years old.

The total photovoltaic system puts out 600 watts of electricity, in full sun, he says, and he expects them to last about 80 years. The cost is going down a little, and incremental changes have occurred in technology as well as cost. “Don’t wait,” he will advise anyone interested in installing a photovoltaic system. “You can be the boss of your own power company today.”

McLean said he’s been thinking about this house for 29 years and has had to make some changes and compromises along the way. He began building five years ago and has done most of it himself, with much appreciated help from friends. Because he has used recycled materials and innovative design, everything has taken about four times as long.

No part of the house is ordinary and no space is wasted. He has taken great care to make it beautiful as well as functional and ecological.

In late October, he was laying odd lots of tile in the bathroom, creating an attractive pattern with slate tiles in the center contrasted with off-white ceramic tiles around the edges. Next will come an ultra low flush toilet that uses about one pint per flush.

Bathroom waste will go into an anaerobic digester along with yard, garden and animal waste to create biogas, a combustible gas that can be used like natural gas. McLean gained basic knowledge of this process in high school and increased it in veterinary school when he did his senior thesis on anaerobic digestion and pathogen reduction.

The greenhouse spanning the length and height of the south side of the house is planned for multiple functions, including food production and harvesting heat. He plans a cantilevered space for sitting and will use low tech approaches to maintaining a comfortable temperature while keeping the use of fossil fuels to a minimum: insulated drapes to cover the inside glass; Mylar drapes on a roller on the exterior greenhouse wall, controlled by a sensor; Styrofoam panels on the interior greenhouse wall, which, he says, will have to be moved manually.

McLean’s belief in using what is available and using as little fossil fuel as possible extends to transportation. With science teacher and friend Tom Stocker, he has been making biodiesel fuel from recycled cooking oil to use in vehicles that they have modified to use either regular gas or biodiesel.

In late summer, McLean with his wife, Suzanne Haviland, a veterinary acupuncturist, and their three young sons traveled to Oregon in their ’86 VW Golf. He removed the back seat and made a frame to fit all the car seats, then stored all the gear underneath. They drove almost 750 miles on one tank of his bio-diesel fuel, getting 43 to 53 miles per gallon. “The faster you go, the poorer the mileage,” he notes. The main problem when traveling is finding another supply of biodiesel, he adds. McLean is putting out a plea for some sort of coalition and listing to let people know where alternative fuel sources can be found.

McLean and Stocker are building a biodiesel plant that will have the potential to make 1000 gallons a day. They built the small one they are now using from used materials, and it makes about 33 gallons. They collect used cooking oil from restaurants and stockpile it until they have enough to make a batch, filtering the oil before cooking.

McLean has learned that diesel engines, including the first one, built in 1893, originally were meant to run on vegetable oil; that first engine ran at 200 RPMs.

Growing all of their own vegetables will be among McLean and Haviland’s future endeavors. Right now, building their house, raising three young sons, pursuing their careers and producing biodiesel take most of their time. They do have good compost piles heating.

Don McLean, DVM, came to the practice of veterinary medicine after several years of working at jobs that challenged him physically and taught him many building skills. He attributes his experience in 4-H as a youth with fostering his interest in the care of animals, and he was drawn to veterinary medicine when he decided to change careers. “I wanted to do something to help animals and country folk,” he said, “and make enough money to live on and have some control over my life.”

He treats his animal patients with a holistic approach that takes into account the entire situation involving the animal, not just the presenting problem. “I prefer to use treatments that are natural whenever possible,” he says, but that wouldn’t exclude the use of conventional medicine. If animal owners are willing, he likes to use folk remedies and herbs when appropriate. For example, raspberry leaf improves smooth muscle tone and the contractions of labor and can be helpful in birthing with goats, cows and sheep. He might suggest comfrey for bone bruises and common plantain for scrapes. Blackberry leaves can be helpful for diarrhea, he continues.

Some of the natural treatments he uses are folk remedies he learned from old-timers in Oregon; others he has learned from study. Corinne Martin, an herbalist in the Bridgton area, has been helpful in this area, he says, and he uses her book, Earth Magic.

Being able to take a sick animal and make it better is deeply satisfying, McLean observes. “There’s a lot of joy when things go right. The flip side is the anguish when things go wrong.” There’s always room for improvement, more to learn about healing, he says, but a certain level of attrition is unavoidable. “The fact is, some animals are going to die. That’s part of the natural process and we can’t control it. We all return to the earth eventually.”

About the author: Joyce lives and gardens in the western Maine foothills and writes about people whose efforts to live a saner life might interest other people as they do her. She contributes to The MOF&G frequently.