|

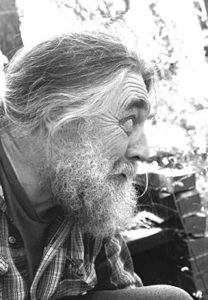

| Jim Cook started Crown O’Maine Organic Cooperative to distribute local and organic produce from Maine farms to natural food stores, restaurants, buying clubs and institutional kitchens. |

Making it Happen in Maine:

Crown O’Maine Takes Distribution to New Levels

by Marada Cook

Author’s note: While objectivity and honesty are traditionally the foremost goals of journalists, The MOF&G has always made my job easy by asking me to cover farmers and food producers I sincerely admire. “Positively spun and helpful to farmers” has been Jean English’s creed, and in writing a piece about my family’s distribution business, I embrace this philosophy ahead of unbiased reporting. This is my family at work. This story comes from my own kitchen table, and is one I’ve overheard and participated in from teenage years to the present.

On Friday afternoons dozens of orders come into the office beside the kitchen at Skylandia Organic Farm in Grand Isle, Maine. “I need a bag of organic whole wheat flour, a case of Nezinscot Farm butter, 50 pounds of ‘Yukon Gold’ potatoes, 10 pounds of mesclun and 15 pounds of fiddleheads.” The Crown O’Maine Organic Cooperative (COMOC) is a specialized distribution business delivering local and organic produce from Maine farms to natural food stores, restaurants, buying clubs and institutional kitchens. Jim Cook works the end of the phone line: His farm is the northernmost in the cooperative, and it is his job to coordinate filling the truck as it heads southward from Aroostook County. Sometimes an incoming order is for a full pallet-load of potatoes, carrots or wheat flour – other times orders are for a single case of cheese, apples or ployes mix.

|

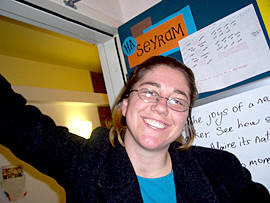

| Leah Cook, Crown O’Maine’s trucker, has traveled 24,000 miles delivering produce in Maine in the past year. |

Driving the Crown O’Maine’s 14-foot Ford box truck is Jim’s youngest daughter, Leah. A 23-year-old trucker with a degree in biology from Reed College, she has logged 24,000 miles for COMOC since she began delivering farm products last September. As she says, “I could have crossed the country eight times in as many miles, but I wouldn’t have met all my farmers and produce people and neighbors across the state.”

Leah starts her delivery run at 6 a.m. on Sunday mornings, making pick-ups from Dionne Farm, WoodPrairie Farm, Nature’s Circle Farm, Thibodeau Farm, Margeson Farm, Ostlund Farm, Aurora Mills, Checkerberry Farm, Goranson Farm, Nezinscot Farm and Thirty Acre Farm. Crown O’Maine carries seasonal produce from a full roster of over 25 farms. This week in June, the first stop planned is the home of a fiddlehead picker from Grand Isle. While obstacles to local food distribution are more often system-wide than case-specific, this time the weak link is a missing-in-action producer.

“What do you mean, he’s not around this week?” asks Jim Cook, COMOC director. “Well, I think he went on vacation,” explains the picker’s brother over the phone.

“Is he coming back?” Jim has sold 150 pounds of fiddleheads, banking on the hope that northern Maine’s cool spring can extend southern Maine’s brief window of picking. Chefs and farmstands have placed heavy orders, knowing this is a one-shot opportunity.

Finding fiddleheads in June has never been a sure-fire thing, but neither has distributing produce for small family farms. Over the years fluctuating supply, variable quality and inconsistent seasons have challenged COMOC’s mission to keep farm-gate prices high, wholesale prices reasonable, product available and customers satisfied with quality. These goals leave just enough margin for COMOC’s carefully customized distribution business. COMOC usually sells root vegetables, grains and value-added products in what is considered Maine’s “off-season” (November-June). Last year Crown O’ Maine extended its distribution season with the reemergence of Maine-grown organic oats, wheat flour, spelt and rye flour. The grain harvest in late August got the Crown O’Maine’s “season” off to an early start – and this year the Crown O’ Maine will run straight through the summer months, filling gaps in early spring and summer availability of items such as greens. New farmers participating in the cooperative effort, new products added to the availability list, a refrigerated truck, and a Newport-based warehouse with a 24’ x 30’ walk-in cooler have made the expanded distribution season a working reality.

When COMOC began 12 years ago, a 15-passenger Ford Club Wagon loaded with hand-picked, hand-packed, hand-loaded and hand-delivered potatoes was the height of its organizational structure. The cooperative had no by-laws, no official members and no officers – and still doesn’t. The “cooperative” nature of Crown O’ Maine comes from farmers working together to pool product, to maintain uniform quality standards, and to ensure that distribution is on time. The family business is an extension of the abilities of a man who left a comfortable career in dealership car sales to go into farming. The Cook family grew up hearing lines like, “It’s not about price. It’s about quality product.” As the five kids grew older, two (Leah and I) returned to Grand Isle to work the farm and cooperative. Learning from Jim’s experience has been part of the expansion process.

“We have never been the classic ‘middlemen,’” Jim says. “We don’t follow commodity pricing. We don’t speculate on farmers’ produce. We ask, ‘How much do you need at the farm gate to make this work for you?’ In order to pay farms fairly, you must recognize that a ‘good deal’ is not just about price. It is about quality.”

Starting with the family farm (Skylandia Organic Farm in Grand Isle), COMOC established its reputation for niche products and for providing chefs and other markets with unusual organic root vegetables. Believe it or not, in 1995, a widely-available, unblemished, good-eating potato was considered an unusual root vegetable. In recognizing and serving the need, Crown O’Maine was the first and became the largest in-state distributor, and out-of-state exporter, of certified organic produce. Jim’s wife and kids meticulously packed each COMOC box that left Skylandia Farm in the Ford van. Twelve years and 25 additional producers later, carrying uniformly quality products remains a strict standard of the cooperative. It has been successful, moving fingerling potatoes, ‘Sunchoke’ Jeruselum artichokes, spring-dug parsnips, organic cranberries, potatoes in all shapes, sizes and colors, wheat from the “breadbasket of the Northeast,” apples for the coast, blueberries for the west, fiddleheads for anywhere south of Bangor, Maine-made sea salt, Beyond Coffee, farm-made jams, Acadian ployes mix, and greens for the spring-season weather gaps. Foods that were once impossible to find Maine-grown, wild and organic now travel the state every two weeks.

Leah Cook’s rounds take her through Hamden, Bar Harbor, Ellsworth, Blue Hill, Belfast, Rockland, Brunswick, Farmington, Skowhegan, Norway, Turner, Augusta, Portland and Portsmouth. They bring her into contact with every facet of the Maine food system. She meets farmers at the warehouse in Newport. She squeezes the delivery truck between liberally-stickered Suburu Outbacks at the Blue Hill Coop. She has encountered an amazing array of personalities, including a farmhand who once caught alligators, and has added her own wry collection of practical tricks to the voices of local food advocates. “Watch out for recycling bins on loading docks,” is one of them.

“I get to see all the back rooms of the stores where MOF&G readers shop,” Leah says. “I meet the produce managers who are stalwart defenders of local organic veggies. They know what customers want – and also what they should want. Their staff unpack the boxes like it’s a perpetual birthday party.” These observations are shared with Jim as they go over the next day’s orders: which restaurant gets the largest potatoes; which baker needs his grain in a hurry; where the special order goes; and the final double-check to be sure nothing has been left out. The two routes–one logistical and one physical – create the beaten track to the company’s motto, “Making It Happen in Maine.”

On the Crown O’Maine Web site, “It” is defined as “a community inter-connected through a self-providing food system that results in strong and vibrant local agriculture,” but it has taken Jim Cook years to turn this from a personal vision into a viable business. In his experience the concepts of food security, local resilience to national and worldwide issues, and “strengthening of rural communities” that are at once so vital and so nebulous, can be made active and real through a fairly-run food distribution system.

“In this equation every member of this team (farmer-distributor-retailer-consumer) must make enough to cover costs and receive value,” Jim says, “The only time there will be a problem is when the cost/value ratio is wrong. When price exceeds value and it doesn’t sell, then we have a problem.” He says this, and then observes, “In 12 years, I can count on two fingers the number of problems we have encountered.”

Farmers quickly found they can ask the price they need to produce the crop. Purveyors dealing with COMOC found the product unconditionally guaranteed and delivery dates timed to their locations for the freshest possible drop-off. Chefs who value good flavor discovered taste is a Crown O’Maine benchmark of marketability. All parties involved have learned, over years of cooperation, that ‘Maine-grown Organic’ is not limited to this year’s crop. If a certain crop doesn’t exist one year, starting dialog with a farmer may bring it to harvest the next. If a “market” seems to be the obstacle, a phone call to Jim may change the entire picture. Dozens of phone calls as early as seven in the morning, countless emails and faxes, and the week-long process of taking requests and compiling product orders for farmers: This is Jim’s part in “Making It Happen in Maine.”

This week, however, “Making ‘It’ Happen” hasn’t happened exactly as planned. On board the delivery truck are greens and frozen strawberries from Skylandia Farm, a freezer and a refrigerator, and a half-ton of fish meal fertilizer for a farmer in Guilford – even after a six-hour delay, though, no fiddleheads have appeared from the St. John River Valley.

Jim shrugs his shoulders as the truck departs. “I’ll have to call everybody tomorrow,” he says, “and apologize.”

Two hours later, a call comes in to the farm. “Hello, is Jim there?” He’s here all right. “Did you need some fiddleheads?” It is not the neighbor who disappeared, but an out-of-the-blue call from a second picker.

“Sorry, the truck left hours ago, but stay in touch for next year,” he says, biting his tongue.

“Most of the time we take the longer view,” Jim says once he’s off the phone, referring to cost-efficiencies. “The attitude that an endeavor must immediately make money or it can’t be done is short-sighted. The first point is,” he says, repeating himself for emphasis, “The first point is that is has to be done.”

No longer biting his tongue, Jim makes a second phone call. “You going towards Boston today?” A muted response comes through. “Got room for four coolers to go to Newport?” Within the hour, Jim has called back the picker, and 150 pounds of fresh fiddleheads are riding south with a tractor-trailer driver from a nearby truck company.

“If you admit that the challenges looming ahead are large,” Jim says, “then you must agree that regional food security will be the backbone of our strength as we face these challenges … to be the strongest link in this chain is COMOC’s mission.”

For more information about Crown O’Maine Organic Cooperative, please visit www.crownofmainecoop.com.