Mark Hutton ([email protected]), vegetable specialist with the University of Maine Cooperative Extension at Highmoor Farm in Monmouth, talked about asparagus cultivation at MOFGA and Cooperative Extension’s 2010 Farmer to Farmer Conference, and Rick and Marilyn Stanley of Chick Farm in Wells, Maine, talked about their experiments with using chickens to control weeds in asparagus.

History and Origin

Asparagus originated along the coastal regions of the Mediterranean Sea, said Hutton. Hence, the crop tolerates up to about 4 mmhos of salt – a fairly high level of salt. At one time, fields were treated with about 2 tons of salt per acre to control weeds. With roots more than 6 feet deep, most of the plant is below the salty top inch of soil. Applying salt, however, is “not something we would recommend today,” said Hutton.

Asparagus has been cultivated for medicinal and culinary uses for more than 2,000 years and was well known to the Greeks and Romans.

The United States now grows about 66,000 acres of asparagus, most in California and Michigan, some in southern New Jersey and upstate New York.

Sales and Marketing

Asparagus brings $4 to $8 per pound. Hutton has heard that the Belfast Coop “is screaming for more asparagus” and pays $6 per pound. “It’s good money for that time of year” – usually May through June.

Wholesale prices are $5 to $6 per pound, but “most of us aren’t going to be producing enough to really look at a wholesale deal,” said Hutton.

The estimated per capita consumption is about 1 pound – which strikes Hutton as low. His family eats about a pound per person per week in season. Data show that you need about 10,000 people to be able to move 1 acre of asparagus.

The University of Kentucky found that a two-year process of establishing an acre of conventional asparagus can cost about $3,500. The first year is a fallow year for preparing the ground with stale seedbedding or cover cropping. Asparagus crowns are planted the second year.

Once established, this hardy perennial will be in production for about 10 years – maybe 15 to 25 in a home garden. Commercially, declining yields after 10 years limit the worth of the crop.

|

| An asparagus spear emerging in spring. Good weed control is one key to productive asparagus culture. Planting new beds regularly is another. English photo. |

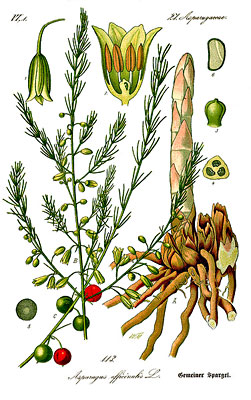

Botany

The asparagus crown is the underground structure, including the rhizome (an underground stem); fleshy roots (a storage organ that lives two to four years), and a fibrous root system (the more active root system, which absorbs nutrients and water and lives for a year to two).

Roots grow more than 6 feet deep, so they can scavenge a lot of nutrients; and typically in Maine, supplemental irrigation isn’t needed because of the extensive root systems.

Asparagus is a dioecious plant; i.e., it has separate male and female plants. Plants with red berries are female. “We don’t want those,” said Hutton. “When we talk about variety selection, I’m going to encourage you to use hybrids that are male hybrids. The female plants are less productive, because they’re putting energy into the seed rather than putting energy into the storage roots.

“The other problem with the female plants is that in many established asparagus plantings, asparagus becomes one of your main weed problems – all of those volunteer seedlings that come up from that asparagus seed.

“If you’ve got a planting that has some females in it, generally it’s going to move toward being predominantly male, whether that’s one of the old open-pollinated varieties or the new hybrids that do have a few females. The female plants aren’t as vigorous, aren’t as long lived, because they’re putting energy into reproduction rather than into storage roots. They’ll start to flower in the first year of production.”

You needn’t rogue out females; but in a new plantation, you shouldn’t plant some of the old, open-pollinated varieties.

‘Purple Passion’ is an exception. Male hybrids are not available, so the population will be about half female, but over time it will shift to more predominantly male.

Site Selection

Asparagus will be in the ground for 10 or 15 years, “so think about where you want it and how it will fit into your overall farm plan,” said Hutton. Plant into new ground; not into ground that’s grown asparagus within the last eight years.

Choose a level field. Because the new planting is clean-cultivated the first growing season, any slope can cause serious erosion then. Harvest is a lot easier on level, stone-free ground, too.

Asparagus doesn’t like wet feet, so select light to medium, well-drained, loamy soil, and don’t plant in fields with high water tables.

Avoid frost pockets. In the warm 2010 spring, asparagus got going early and then got hit by frost in many places, putting a lot of growers out of production for about 10 days. Frost causes hooking, i.e., hook-shaped spears. (Hooking can also be caused by feeding by asparagus beetle larvae that are in the soil, or cutworms.) “All you can do when you see frost injury is clean cut the field, put those spears in the compost, and let the next flush come out,” said Hutton.

Also avoid fields with perennial weeds. Weed control is a large part of asparagus production. Asked if straw mulch can be used to control weeds, Hutton said yes; but wood chip mulch won’t work, because the other tool for weeding is shallow tillage.

“When we’re done with harvest in the spring, we’ll set our rototiller so it will only go down about an inch, an inch and a half,” and rototill the field to take out weeds. Bark mulch or shredded bark will interfere with rototilling over the top of the bed, but straw can be worked back in.

Conventional growers use cover crops after the final harvest or overseed rye into the crop in August, then will kill the cover crops in the spring, just before the asparagus emerges, with an herbicide. Organic growers might be able to use oats, said Hutton, since they’ll winterkill.

Hutton doesn’t know anybody who is growing asparagus on black plastic or landscape fabric but says that could be an effective way to manage weeds – especially during the establishment year, when asparagus competes poorly with weeds.

Field Preparation

The year before establishing an asparagus planting, eliminate all perennial weeds through tillage, fallow ground, stale seedbeds, and/or cover crops such as clover or soybeans. Also apply lime where needed. “Once you stick that crop in the ground, it’s a perennial,” said Hutton; “so changing the pH by lime applications is going to be hard to do, because you’re not going to be doing that kind of tillage.

“If you’ve got a plow pan or suspect you’ve got a plow pan, subsoiling or chisel plowing to help break up that plow pan the year before is a really good idea. This is the only chance you’ll get to do that.

“This is one crop where soil testing is very important You need to know what you need to apply in the planting year – particularly for pH and phosphorus [P]. The phosphorus is going to go in at planting time, and then you’re pretty much done applying phosphorus, because you’re not going to get it down where it’s needed [after that].”

Recommendations commonly call for incorporating the P into the trench when you plant asparagus, because P doesn’t move very well through the soil, so it must be put it where the roots are. “You have one chance to do that.”

If potassium (K) and P are recommended after planting, they are applied to the surface, and “requirements are usually pretty low on our soils and are usually needed only on alternate years. On lighter, sandy ground, requirements for potassium could be a little higher.”

Nitrogen is typically applied as a split application – 50 to 75 pounds per acre before spring harvest (some time in April) and another 50 to 75 pounds at the end of June, after harvest. “We’re trying to promote a lot of good plant growth to try to put a lot of storage energy back into the crown.”

When Hutton compared organic with conventional production at Highmoor Farm, he used just compost on the organic plots, at about 12 yards per acre in a split application, banded over the top of the row. (A yard of compost weighs about half a ton, although conversion is imprecise because the moisture content of compost varies.)

Manures work fine in asparagus, Hutton continued, “but put it on after the final harvest at rates of 5 to 10 tons per acre. The problem with manures is bringing in weed seed.”

In the establishment year, some irrigation might be helpful, but once the crop gets going, “we get enough rainfall and our soils are heavy enough that irrigation is not something you’ll have to be too worried about,” said Hutton.

Spacing and Planting Depth

Plant asparagus about 5 to 8 inches deep. In heavy soils, plant at the shallow end of the range; in light soils, deeper. Shallow planting leads to earlier emergence and earlier harvest in the spring – which can be good but can produce more frost injury in cold springs. Shallow plantings also tend to produce higher yields but smaller spear diameters.

Asparagus crowns work their way up in the soil over time because new crown material builds on top of old. Because organic growers want to be able to do shallow tillage, and because shallow crowns create smaller spears, most Maine organic growers will do better with deeper planting.

“USDA grading standards for asparagus have at least five size classes,” said Hutton, “all based on diameter. For fresh markets, as long as it’s all roughly the same, probably no one will complain. But deeper plantings give bigger, thicker spears.

Planting

Plant rows in a north-south direction – or with the prevailing wind – to minimize foliar diseases (particularly rust disease; and Cercospora, although it’s not prevalent in Maine) by promoting quickly drying of foliage.

Rows should be 4.5 to 6 feet on center. “Most of our recommendations on row spacing have more to do with the equipment you’re working with rather than what the plant needs,” said Hutton. “The ferns can get pretty big, and it depends on what you’re doing to manage the area between the ferns. If you’re going to have grass strips, you want to have those rows far enough apart that you can get in there and mow. If you’re going to clean cultivate, then you want the rows closer together.”

In-row spacing should be 10 to 18 inches. “The tighter spacing will increase upfront costs for more seedlings, transplants or crowns. You’ll come into production earlier but you’ll have smaller spears. Peak production might occur during years three to five. Wider spacing takes longer to come into production, but spear size tends to be greater once you hit full production, and wider spaced plantings will stay productive over a longer period of time. Years four, five or six may be your peak years of production, and high production will continue for a longer period than for tighter in-row spacing. Tighter in-row spacing creates more plant-to-plant competition within that row.” Typically a plant produces eight to 12 spears per year.

The following table shows the number of crowns or transplants needed, depending on spacing.

Asparagus crowns/transplants needed per 1/4 acre

| In-row distance | Distance between rows | ||

| 4.5 ft. | 5 ft. | 6 ft. | |

| 10 | 2,904 | 2,614 | 2,178 |

| 12 | 2,420 | 2,178 | 1,815 |

| 14 | 2,074 | 1,867 | 1,566 |

| 16 | 1,815 | 1,634 | 1,361 |

| 18 | 1,613 | 1,452 | 1,210 |

Crowns sold in lots of 100 cost about 50 to 75 cents each.

Plant when the soil temperature is at least 50 degrees, in early to mid-June. Make a W-shaped trench, put the plant in the bottom of the trench, cover it with about 2 inches of soil, and then, with three to five cultivations over the next month or so, add 1 to 2 inches of soil to the trench each time, slowly filling the trench with soil as the plant grows – but never covering the whole plant. By mid-July the trench will likely be filled.

Cultivar Selection

Walker Brother Farms in Pittston, N.J., works closely with Rutgers’ asparagus breeding program and produces the ‘Jersey’ asparagus cultivars. The University of Guelph in Ontario, under David Wolyn, is the source for two other cultivars that perform well in Maine – ‘Millennium’ and ‘Tiessen.’

Hutton recommends choosing hybrid male cultivars. Most new cultivars have high tolerance to Fusarium disease, the major limiting factor in growing asparagus.

The Canadian (‘Tiessen’ and ‘Millennium’) and New Jersey (‘Jersey Giant,’ ‘Jersey Supreme,’ ‘Jersey Gem,’ ‘Jersey King’ and ‘Jersey Knight’) series work well in Maine (although ‘Jersey Gem’ has been dropped). ‘Jersey Giant’ and ‘Millennium’ are probably the two most common cultivars in commercial production in the East, said Hutton. California cultivars lack the winter hardiness needed in Maine. Open pollinated cultivars don’t yield as well and lack Fusarium tolerance.

“Fusarium is what’s going to take out your asparagus planting,” said Hutton. “That’s why it’s only productive for 10 to 15 years on a commercial scale. In New Jersey, the production cycle is only five to seven years before they take a planting out, because the amount of Fusarium in the soil builds up so much and reduces the productivity of the planting. In Maine, we’re not working the plants so hard, and the soils are colder, so we don’t get such a rapid buildup of Fusarium.”

Crowns vs. Transplants

Quality crowns are available for most of the commercially important varieties. Don’t buy two-year-old crowns: They’re less expensive but also less vigorous than 1-year-old crowns.

When you first get crowns, cut through a few roots to check for discoloration in the internal tissue, said Hutton. Roots should be white. A reddish-brown color may be Fusarium. If they are brownish, contact the supplier and send them back.

Healthy crowns should then be sorted by size (large, medium, small; don’t use the very small ones). Plant crowns of similar sizes together, because they’ll all be yielding similarly.

With crowns, previous recommendations were to wait two years before the first harvest. Most current research says you can take a small harvest the year after planting crowns.

Transplants take 10 to 12 weeks to grow from seed. Growing asparagus from seeds and transplants will add an extra year before harvest. Hutton recommended using a large cell size (1.5-inch x 1.5-inch x 2.0 inches), and he used 3-inch peat pots. Germination takes 10 to 14 days at 75 to 85 F, according to the books, but at Highmoor, on heat mats kept at 80 degrees, seedlings took three weeks to emerge.

Keep germinated seedlings at 70 to 75 F during the day and 60 to 65 F at night. Plants can be set on a hardware cloth bench so that roots are air pruned and plants don’t send out a big taproot.

If you save seed to grow your own asparagus, pick fruits when they’re completely red, said Hutton. You should get 50 percent male and 50 percent female plants from that seed.

Harvest

At Highmoor, the first harvest occurs consistently between May 2 and May 6, regardless of the weather; and they harvest for eight weeks.

Harvest spears daily once production begins, cutting or snapping them 1 to 2 inches below the ground, taking care not to damage nearby spears in the process. Don’t cut spears at soil level, since the remaining spear will continue to grow and will prevent other spears from sprouting. Thin, whippy spears should be cut, too. “The better job you do keeping spears cut during harvest time, you’ll keep more spears coming up,” Hutton explained. “Think about apical dominance in plants. Spears produce auxins, which prohibit the breaking of other buds on the crown. If spears are allowed to fern out, the plant ‘thinks’ it’s producing leaves and doesn’t have to send any more spears up.”

Keeping the planting clean cut during harvest also reduces harvest time dramatically, because you’re not trying to work around other spears that have started to leaf out.

A mature planting may be cut for six to eight weeks; then let all emerging growth fern out.

For fall harvests, let spears fern out in the spring, mow them in late July or early August, and then harvest spears until frost. Don’t harvest in spring the following year. Growers who are trying this in Pennsylvania and the Carolinas find that they have to harvest at least twice per day; a spear that was almost tall enough to harvest in the morning – say 5 inches tall – is 18 inches tall by afternoon.

If you have the space, try moving part of your planting to a late summer or fall harvest cycle. You can maintain these as fall beds, or let them grow into ferns the following summer and don’t harvest them again until the following spring.

Post-Harvest Handling

Unless you have a big plot, you’ll probably harvest and hold your crop for a couple of days before market to get enough to sell. Stored under cool (35 F), moist (90 to 95 percent relative humidity) conditions, spears hold for 10 to 14 days. Chilling injury (pitted and water soaked spears) occurs below 35 F, while under warmer temperatures, spears continue to elongate, sugars decline, and fiber (lignin) increases.

Store spears standing upright to prevent curving. Asparagus has negative geotropism – it bends away from the direction of gravity. It can lie flat in a tray for a day or two, but after 10 to 14 days it will bend significantly.

Storing spears in water is controversial now because of potential bacterial contamination.

Postharvest Growth

Next season’s crop comes from buds produced during the current season. Keep the plants actively growing after harvest and until the soil temperature drops below 50 – when plants go dormant – because that growth produces buds on the crown for the following year; these buds will break the following spring and become spears.

When spear size shifts from large and thick to a lot of scrawny spears, either the plants are too old and it’s time for a new planting, or the soil may not have enough nitrogen to get enough storage reserves back into the crown.

In the fall, once ferns start to turn yellow, you can mow them off or leave them intact, depending on your spring market. Fall mowing that removes a lot of the organic material from the field makes the beds warm up faster in the spring, producing an earlier harvest; but ferns left on the planting in fall hold more snow in place, reducing winterkill in the planting. In the spring, however, this organic matter will keep the soil cooler longer and delay harvest somewhat – which may be helpful by delaying spear emergence until after the greatest probability of frost damage has occurred.

Insects

Spotted asparagus beetle and common asparagus beetle larvae feed on the foliage and can defoliate plants. Plants can take a lot of feeding injury, but good IPM threshold numbers aren’t available to let growers know when to control beetles.

Adults overwinter in debris around the plants and move into the field as spears emerge. Their feeding can cause some hooking and crooking. Clean cultivating in the fall might help limit their numbers if the soil is low in organic matter as well. Beetles would then overwinter at the edges of the field, and clean cultivation would slow their movement into the planting the following spring. Most organic growers, however, have a lot of organic matter in their soils.

Beetles are fairly easily controlled with Pyganic and Entrust (spinosad), probably because so little spraying has occurred so far, so resistance has not built up. The larvae are the most susceptible stage, while adults are mobile and hard to spray. Both larvae and adults can cause a lot of damage, but plants can survive a lot of damage and still send a lot of photosynthates to the roots.

Japanese beetles, tarnished plant bugs and cutworms can also be problematic, and the asparagus aphid injects a toxin that causes a small witch’s broom to occur on the plants.

Weed Control

Weed control is the biggest issue in organic asparagus production and is extremely important in the establishment year. Till shallowly with basket weeders or with a rototiller after the final harvest in the spring or summer; then hand weed for the rest of the season. Avoid using a disc. Weeder geese or chickens can be helpful, as can cover crops that are winterkilled, such as oats. Conventional growers can use cover crops and control them the following spring with herbicides.

One grower said that heavy hay mulch controls weeds well in his plot. He pulls it back in the spring to enable plants to grow, and uses a little hand weeding for further weed control.

Diseases

Six diseases attack asparagus, but only two are problematic in Maine. If disease occurs – and it will, said Hutton – all you can do is try to “outrun” it and have your next planting ready to go.

Fusarium wilt or root rot (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Asparagi) is a soilborne fungus that accumulates over time and can be intensified by nutrient stress (too little or too much fertility), drought and insect damage. Hutton recommended choosing the new hybrid varieties that have high levels of Fusarium tolerance and ensuring that you buy disease-free crowns by cutting some crowns open to make sure they don’t have brown, discolored tissue.

Asparagus rust (Puccinia asparagi) is controlled by using resistant varieties, orienting rows to keep foliage as dry as possible, removing the source of inoculum through sanitation and by removing volunteer and wild asparagus around the planting, and not over fertilizing plants.

Yields at Highmoor

Hutton grew seven cultivars (‘Tiessen,’ ‘Jersey Gem,’ ‘Jersey King,’ ‘Jersey Supreme,’ ‘Millennium,’ ‘Jersey Giant’ and ‘Jersey Knight’) at Highmoor, in conventional and organic plots with similar nutrient levels in both. The organic (compost amended) plots had, if anything, less N than conventional, which received 10-10-10.

For most cultivars, the organic plots outyielded conventional. For ‘Jersey Gem’ and ‘Jersey King,’ organic and conventional yields were the same. Hutton thinks the numerous benefits of compost caused the yield differences. Also, in organic plots, hand weeding and tillage were used for weed control, resulting in weedier plots with a lot of quackgrass, thistle and milkweed. In conventional plots, an herbicide was applied once in the third and once in the fourth harvest year, “and I think we set the plants back a little bit. I think they’re not as herbicide tolerant as we may think,” said Hutton.

Regarding organic plots, “Through the five harvest years, by the time we got into the peak harvest yields, cull yields went way up for all the cultivars. Spear sizes varied more by year than by varieties; any of the varieties will be acceptable regarding spear size.”

Top yielding cultivars were ‘Tiessen,’ a greener cultivar, and ‘Jersey Giant,’ which can have a nice purple tinge. ‘Tiessen’ is a little harder to come by. “In Ontario they’re pushing ‘Millennium’ more,” said Hutton – another cultivar he recommends, along with ‘Jersey Supreme.’

At Highmoor, 100 row feet of these cultivars produced 20 to 30 pounds of marketable crop and 8 to 12 spears per plant.

Hutton doesn’t see any advantage to planting more than one variety, unless one of them is ‘Purple Passion,’ which is open-pollinated and beautiful, and 20 percent higher in sugars than green varieties. When cooked, it turns green – but it’s very tasty raw.

Hutton added that blanched asparagus could be produced with hoops and opaque cloth, or barrels – but Maine has little demand for blanched asparagus.

Weed Control with Chickens and a Cover Crop

Rick and Marilyn Stanley of Chick Farm in Wells, Maine, presented results of their weed control experiments supported by a USDA SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education) grant.

The Chick Farm has been in the Chick family for generations and was a poultry farm until the 1970s, before it became inactive for several years. Rick and Marilyn started raising mixed vegetables and eggs in 2001 and became MOFGA-certified in 2002. Basically a two-person operation, the farm raises about an acre of crops.

The Stanleys added broiler production in 2007, and now they’re starting to move away from mixed vegetables and toward crops that do better on their sandy soils – much as experienced farmers suggested when they started, recommending crops such as asparagus and strawberries.

The Stanleys are part of the York County Farmers’ Network, a collaboration of some York County farmers and Cooperative Extension that meets monthly and has twilight meetings in the summer with guest speakers.

Why Organic Asparagus?

Asparagus is a high-value crop with strong market demand that grows well in the Northeast and is well suited to sandy soil, said Rick. Drawbacks include the high start-up costs and weed control.

Their grant proposed a two-part weed control strategy: for quackgrass, a 10-foot-wide, tilled barrier around the asparagus planting. They’ve heard that a 4-foot barrier is the minimum; because they had an 8-foot tiller, they chose the 10-foot width.

For annual weeds, they let “weeder chickens” forage in the asparagus after harvest. While chickens can be destructive when asparagus spears are just emerging, once the plants fern out, the stems are tough and the chickens don’t harm them. Also, by putting chickens in after the harvest, there’s no conflict with the waiting period before applying manures in organic production.

Because the crowns are planted fairly deep, chickens generally don’t damaged them – “but you do need to keep an eye on that,” said Marilyn, “because they’ll dig deep.” While chickens eat weeds, they also fertilize the asparagus.

They also looked at straw and hay mulches.

Establishing the Planting, Mobilizing the Hens

The Stanleys established two 50- by 100-foot plots about 200 yards apart. Both had been in organic crop production and were relatively weed free – although in retrospect, the Stanleys wish they had spent a year cover cropping for further weed control before planting asparagus. The ground was level, with a light sandy soil.

Hybrid ‘Jersey Supreme’ crowns were spaced 15 inches apart within rows and 8 inches deep, with rows 80 feet long and 4 feet apart. The Stanleys buried heavy-duty drip tape in the trenches during planting. “It turned out to be a mistake,” said Rick. “Rodents chewed it all up, chickens dug it up; when I mowed, I got it wrapped around the bushog …”

They made a V-shaped trench with their moldboard plow and filled the trenches over time with shellfish compost.

They tilled a 10-foot-wide weed barrier around the asparagus planting and grew oats and winter rye as cover crops in the barrier; both worked fine. “We’d had good luck in the past using the allelopathic effects of winter rye to kill quackgrass,” said Marilyn. “But we found that you can do anything with that barrier, as long as you till it a couple of times a year.” Planting lettuce was “a good use of that space,” said Marilyn.

Rick built a “chicken tractor” (moveable coop) large enough for 30 to 50 laying hens. An “inner sanctum” elevated off the ground has 1-inch chicken wire for a floor, and a door that is closed at night so chickens are protected from predators. Nests are in the back of the coop, for easy access to eggs. The coop is rugged enough that Rick can attach a chain to it and drag it with a tractor. It has double 2×6 skids on all sides.

Premiere One plastic electric fencing (portable sheep fencing adapted for poultry) confined the chickens and kept predators out. “It works way better for keeping predators out than for keeping chickens in,” said Rick. “But if you keep them in a place where there are plenty of weeds for them to eat, they don’t want to get out.”

Chickens were deployed after the asparagus ferned out, with the coop on the edge of the field. Each plot was divided in half lengthwise, with chickens grazing on one half.

For mulch comparisons, each plot divided in half crosswise. Straw mulch was applied on one half, hay mulch on the other. Because hay mulch has weed seeds, the Stanleys wanted to see if chickens would control those seeds and their weeds. However, they did not get good weed germination that year – even though they used their bale chopper and blow mulcher to spray mature hay full of timothy seed. (They use this system to mulch many crops.)

“All the time we get weed seeds,” said Rick, “especially in oat and rye mulch. That’s why we did the experiment. We sprayed half old hay on one side that was full of mature timothy seedheads, and the other half full of oat seeds, and nothing came up.”

They planted asparagus crowns in May 2009; did not apply mulch that first year because the asparagus was growing so slowly that they realized they wouldn’t be able to put chickens in soon – so they left the ground bare so that they could cultivate for weed control. They deployed the chickens around Labor Day, once the asparagus was big enough. The chickens were in for about a month and did a good job. Then the chickens were removed, and the Stanleys planted winter rye on parts of their barrier in September and oats on other parts in August; and cut the asparagus ferns and fertilized the plots in November.

In the spring of 2010, they tilled in the winter rye. The spring was so warm that the asparagus began emerging during the second week of April – before the farmers’ market had started. So the Stanleys let the asparagus grow and fern out. When the freeze came in May, it hit one planting, “singeing” the ferns, and not another 200 yards apart, which was beside a wooded gulley into which cold air drained, and had protection from trees. After the frost, new spears emerged, and the Stanleys harvested that planting for two weeks. They mowed the other planting down in July and harvested it as a late summer crop. They put chickens in each plot after harvest, and cut the ferns and fertilized the plots in November.

Because they couldn’t put the chickens in as early as they’d hoped that first year, weeds grew at times.

Conclusions

The Stanleys concluded that the tilled weed barrier was very effective. “We’re now doing the same thing with rhubarb,” said Marilyn. “As long as you get in there and till it a couple of times. We did use it for a variety of annual crops. Both cover crops worked fine. You could even cover crop for the whole season if you wanted.” They recommend tilling at least twice (spring and fall) and having a barrier at least 4 feet wide. “More is better.”

They think the chickens worked, as well. They can’t be used until late the first year, they found – so other weed control methods are needed until then. If weeds get too tall, the chickens generally ignore them. “They tend to look down,” said Marilyn. “Sometimes we just went through and yanked the tall ones out.”

They noticed behavioral differences among breeds. Buff Orpingtons were very good foragers – “almost too good,” said Marilyn.

“Once they had eaten most of the weeds in there, they decided they wanted to fly over the fence and find something else to eat.”

“You’ve got to keep them busy,” said Rick. “Move them into another asparagus patch with a lot of weeds. That’s all you’ve got to do.”

This year they had some Production Reds (a cross between Rhode Island Red and New Hampshire Red), which were good but not quite as efficient as the Orpingtons, said Marilyn. They also had Black Australorps, which seemd a bit more timid, more hesitant to go to the other end of the field. But “get them so they’re comfortable,” said Rick, “and they do well.”

The orientation of chicken tractor is important. At first Rick set it in the middle of one side, with the door at one end. The hens would come out the door and go under the asparagus ferns, where they were sheltered from predators. They weeded well in there but wouldn’t go to the other end of the plot, because they had to go around the back of the chicken tractor – and they couldn’t see the door from there. If anything scares them, said Rick, they want to be able to see the door. After he put an opening in the other end of the chicken tractor, the birds went to the other end of the asparagus plot. “I found out,” said Rick, “to fool a chicken you’ve got to be smarter than a chicken.”

The Stanleys recommend stocking eight to 15 chickens per 1,000 square feet, depending on the age and breed of the chickens and the weed population. They had 18 Buff Orpingtons in a 2,500-square-foot space. After four weeks, the chickens were getting bored and were starting to dig down to the crowns. “We were surprised how few chickens it took,” said Rick. With the younger, smaller Black Australorps, they put 50 in the 2,500-square-foot space.

Not only did chickens control weeds while they were in the plot; they also set back the fall and spring weeds quite a bit.

To summarize, the Stanleys recommended starting with a fairly weed-free plot and manage weeds by other means during first year – getting rid of quackgrass, especially, before planting.

Position the chicken tractor so that chickens feel safe roaming through entire planting.

Delayed (fall) harvest is possible and can help extend the harvest season.

Neighborhood dogs can crash through or getting tangled in portable fencing.

The Stanleys still hope to compare straw with hay mulch; and to see if slower-growing broiler breeds will forage enough to control weeds. They may try planting forage crops in the pathways. They’re also curious as to whether weeder chickens will work in other perennial crops, such as raspberries or grapes.

Because of the short harvest period in 2010, they did not notice a difference in yield between plots with and without chickens.

Discussion

Pasturing Chickens

John and Mary Belding of Little Falls Farm in Harrison, Maine, have pastured chickens in their 25-year-old, 20- by 50-foot asparagus bed for three years, inside Flexinet fencing. In 2010 they added ducks, which “do a scorched earth thing,” said Mary, although she added that ducks and chickens don’t control milkweed well.

The Lifespan of a Bed

Is it worth keeping a 30-year-old bed? Paul Volckhausen of Happytown Farm in Orland said he did a good job of preparing the ground for his ‘Martha Washington’ asparagus planting and of controlling weeds in the early years. He planted the crowns about 18 inches deep – the recommendation at the time – and he tilled the plot each April about an inch deep. For the first 10 years, production was “incredible” and the spears were easy to sell. Over the years, however, weeds started coming in and asparagus crowns started growing closer to the surface, so they couldn’t till the plot any more. Yields started going down.

Hutton explained that asparagus crowns are underground stems that keep building on top of themselves, which is why they become closer to the surface over time.

Finally, said Volckhausen, after two winters in a row with no snow but about 2 inches of rain in January followed by a sudden temperature drop to about -25 F, the crowns popped out of the ground, leaving few intact plants. Also, because ‘Martha Washington’ self seeded, their rows wander, so they can’t rototill between rows easily. The Volckhausens are ready to abandon that plot.

One participant said her father attributes the continuing success of his older asparagus bed to having prepared a 3-foot-wide by 3-foot-deep trench for it and filling it with manure.

Jo Barrett of King Hill Farm said their 20-year-old bed has also been in decline for years. Scuffle hoes don’t work well for weed control because they take of the tops off spears that are about to emerge.

Hutton suggested starting a new bed about every 10 years (including the year of establishment). “If you think your bed is going to have a 10-year life span, in year seven, start the new bed, so that one’s coming into production while this one’s petering off.” Separate the beds – farther is better – and never go from the old to the new bed with any kind of cultivation equipment without first power washing the equipment. Better yet, cultivate the new bed first, then the old bed. The Fusarium species that attacks is specific to asparagus, so you can grow any other crop on the old asparagus area – cucurbits, tomatoes …

Volckhausen noted: “If I look at the labor I’ve put into that bed in the last 10 years, I would have been way better off starting a new bed. But I’d never heard that a bed had a life of 10 years.” Instead he had heard of decades-old home garden plots.

“There’s a big difference,” said Hutton, “between having enough to eat and having enough to go to market.”

To get rid of an old bed, till it under, said Hutton – “and just know that you’re going to have asparagus weeds in whatever crop is there for a while.”

“I’d treat it as if you’re bringing a field out of sod,” said Eric Sideman, “and spend a year preparing the ground for the next crop.”

“Put pigs in,” said Volckhausen. “Pigs will root it up and kill it.”

Calendar of Care

In the spring, till the bed about an inch deep before the asparagus emerges. Rob Johanson topdresses then with fishmeal – about 45 pounds N equivalent per acre. He has a propane burner, so instead of rototilling, he burns the old foliage (mowing it first if there’s a lot).

Then comes harvest. Hutton said a lot of the research now shows that a small harvest in the second year – 10 days maximum – should not impact the third year’s growth. In the third year, harvest for two weeks. Add a week the following year and keep adding time until you’re harvesting for about six weeks.

Sometimes Johanson mows between the rows when the grass gets growing; sometimes he’s mowed the whole plot down when the weeds got so tall that he couldn’t find the asparagus spears; then the spears would come back up. After harvest, Johanson often ignored the plot because of time constraints on their diversified farm.

Richard Frost has a 3-year-old, 60-foot bed at his Frost Family Farm. After the second year he mulched heavily with about 12 inches loose hay, spread about 12 inches out from the ferns after they emerged, working it between the stalks as much as possible. In the spring of the third year, he pulled the mulch back from either side of the bed and harvested the spears as they came up. Then he pulled the hay back in and added another 12 inches of loose hay to either side of the row. He hasn’t had any trouble with weeds. One grower said she’d had a problem with slugs when she used mulch. Slugs can make spears grow crooked.

After harvest, topdress with fish or compost. Apply 150 pounds of nitrogen (N) per year as a split application of materials such as fish or compost (whatever is cheapest per pound of N) – half (50 to 75 pounds of N) in the spring, before the spears start to emerge; and half after harvest is over, said Hutton. Sideman added that fresh manure can be used for the postharvest application.

At the same time as the second N application, you might hill the plots a little to compensate for the crowns that are growing closer to the surface.

If you’re using chickens for weed control after harvest, you can estimate the amount of N they deposit in manure by recording the amount of feed they consume, said Johanson.

Let the ferns grow after harvest to photosynthesize and provide energy to the root system for the following year’s spear production.

Fall is not a good time to apply manure, said Sideman, because you’ll lose much of it over winter – especially chicken manure, which is so soluble. He recommended storing manure over winter and then using it the following year, after harvest, to comply with NOP regulations for manure applications, and because an actively growing crop captures the most soluble N. Putting compost on in the fall would be better than putting fresh manure on, but Sideman said he’d still recommend waiting until spring, even for compost. Also, growers cannot legally spread manure between December 1 and March 15 in Maine.

Volckhausen said he used to apply compost in the spring when he was tilling, if the soil was dry enough that he could get a manure spreader on the land, and he’d till it in lightly. He always dug down first to see how deep the new spears were.

Hutton said that on their heavier, wetter soils in Monmouth, they till in June, after harvest. They do a clean harvest, leaving no spears sticking up; then they till the entire field, not worrying about nicking new spears, because they were finished harvesting for market.

Watch for asparagus beetles as the ferns are forming. Sideman recommends clean harvesting during the harvest season, leaving nothing for the asparagus beetles to eat when the adults awaken from hibernation in the spring. “You can starve a bunch out that way.” (Although in the first year you don’t harvest anything.)

Volckhausen said he’d read not to harvest anything smaller than your little finger – but following that advice would leave fronds behind for asparagus beetles to feed on. “The size depends on the size bud,” said Hutton. “You’re suppressing the big buds when you leave those small ones,” added Volckhausen.

Depending on the year, three to five or six generations of asparagus beetles may emerge. They have few alternate hosts, and they fly well.

When fronds turn yellow, they can be removed to remove a source of rust spores. Highmoor mows theirs in the fall because they know it will be too wet to get into the plot in the spring to mow. If you have light, sandy ground that you can get onto in the spring, he advised leaving the fronds on over winter to catch snow, which provides some frost protection.

Hutton said the plants don’t seem to benefit from mulching over winter. If you do mulch, remove or till the mulch in in the spring so that the soil warms as early as possible. That will help control slugs, too.

Soil Nutrients

Most P (70 to 100 pounds) should be in the soil before planting the crop. Use a split application for K, with 75 to 100 pounds per application, depending on the soil. “Different researchers are suggesting that you need [K] and others are saying no – once you get K in you don’t need any more,” said Hutton.

Asparagus tolerates a pH of 6.0 to 7.2, but 6.5 to 7.0 is best, since a pH below 6.5 favors Fusarium. If you’re in the 6.5 to 7.0 range, most soils will supply sufficient micronutrients.

Companion Planting

Sideman knows one grower who sows crimson clover in his asparagus in late spring, after harvest. It dies down in winter. It grows quite tall during the summer, possibly favoring diseases because of increased moisture in the plot, and possibly competing for nutrients. It does add organic matter and fixes nitrogen.

Mary Belding has put oats in the pathways and they did well. She didn’t mow them. The asparagus shaded the oats so that the oats weren’t too competitive. Direct seeded lettuce didn’t do well, but transplants did. (Belding has read that asparagus roots produce a chemical that inhibits germination of other plants.) The problem with intercropping is harvesting through the jungle of asparagus fronds. She’s also tried white clover, but it migrated into the asparagus and became a weed.

One gardener stakes and trellises her asparagus fronds and transplants parsley at the base of the rows.

Japanese Beetles

While Japanese beetles occur on asparagus, no one in the session had noted that they damaged the crop much. Sideman said not to use Japanese beetle traps, because they lure the beetles in from miles around and then catch only about 80 percent of them. He said you might put them on the perimeter of your land to draw beetles away from your crop. Beneficial nematodes control Japanese beetle grubs much better than milky spore disease does, but nematodes don’t control the adults, which are strong fliers and come in from all the fields around you. If you’re isolated in the woods, and you have the only sod for miles around, nematodes might work.

One tip – unproven – is to place a Japanese beetle trap in your planting, cut out the bottom of the trap, and let the beetles fly into it and fall to the ground, where chickens can eat them.

Economics

Establishment costs are about $3,500 per acre. A good yield is about 2,000 pounds per acre, or 20 to 30 pounds per 100-foot row. Labor costs vary widely. The wholesale price is about $6 per pound, but growing the crop involves a lot of labor. The market demand is wide open. Managing weeds in the summer on a diversified farm is the big problem. The same is true of strawberries.

Staking

Hutton said that staking isn’t necessary for the plant. The few stalks that fall over and break aren’t an issue. Staking may help the grower with management, though.

Resources

Asparagus Crown Production, North Carolina State University; www.ces.ncsu.edu/depts/hort/hil/hil-2-c.html

Commercial Asparagus Production, North Carolina State University; www.ces.ncsu.edu/depts/hort/hil/hil-2-a.html

Asparagus, University of California Davis; https://vric.ucdavis.edu/veg_info_crop/asparagus.htm

Asparagus, Oregon State University; https://nwrec.hort.oregonstate.edu/asparagu.html

Asparagus Production Management and Marketing, Ohio State University; https://ohioline.osu.edu/b826/

Asparagus Information Bulletin, Cornell; https://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/factsheets/AsparagusInfo.htm

2010 Ohio Vegetable Production Guide – Asparagus and Rhubarb, Ohio State University; ohioline.osu.edu/b672/pdf/Asparagus.pdf

ID-56: Midwest Vegetable Production Guide for Commercial Growers 2003 – Asparagus, Purdue University; www.hort.purdue.edu/rhodcv/hort410/ID562003/index.htm

Growing Asparagus in Minnesota, University of Minnesota; www.extension.umn.edu/distribution/horticulture/DG1861.html

Organic Asparagus Production, by George Kuepper and Raeven Thomas, Dec. 2001; ATTRA, www.attra.ncat.org (attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/PDF/asparagus.pdf)