|

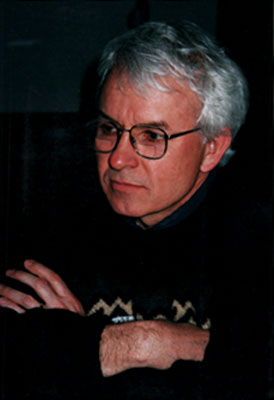

| “A vision of food security makes room at the table for everyone,” said Mark Winne at MOFGA’s Spring Growth Conference. English photo. |

MOFGA’s Spring Growth Conference, March 23, 2002, Unity, Maine

My involvement with Maine, food and agriculture goes back to my college days at Bates College. Those were the days – the early days of food security, of the “back to the land” movement, of the early-organic period, of trying to take control of one vital facet of our lives – namely food. We started by trying to organize the Lewiston community, which in the late ’60s and early ’70s was a place that seemed woefully bereft of all options. Students from Bates, students from other colleges who had grown up in the area, and so-called “townies” joined together to provide counseling to young people whose only destiny seemed to be a lifetime of toil in the Satanic Mills.

Our only credentials were the passion we wore on our sleeves and the absolute certainty, possessed by everyone in their late teens and early twenties, that everything we did was just and righteous. With youthful bravado we took on the local forces of darkness and evil, advocated for the downtrodden, and organized breakfast programs (we actually imagined that we were the Maine version of the Black Panthers), and provided drug and alcohol counseling to the city’s young people. The only qualification that we had to render the latter services was, of course, our own experience with controlled substances.

While I am almost certain that we helped no one, I am just as certain that no one was harmed. We took Mark Twain’s advice to heart: “All you need in life is ignorance and confidence – success is sure to follow.”

But 30 years has elapsed since those days of derring-do and damn the torpedoes, when the yearning to actually help one’s self is sometimes camouflaged by the desire to help others. Upon reflection I think we were motivated by the desire to gain some measure of control over our lives, to feel connected to something, anything, to feel full, replete with the world around us, and, if nothing else, to ward off the arrows of alienation that always seemed to swarm over our heads.

Looking back over the time in between, it really is no surprise that so many of us have turned to food, farming, and smaller communities to keep our feelings of alienation at bay and, perhaps, to bring a sense of security to our lives. That is why I am fascinated these days with the connection between food, security, and community, because I sense larger meanings that transcend the common or functional usage of those words. The terms “food security” and “community food security” are not academic descriptions of a set of economic and social arrangements within our food system, but speak more directly to values, traditions, and longings deeply embedded in our hearts and collective consciousness. And as our food comes from the earth, it is not surprising that we should look to the ground we grow on for signs of physical safety, public health, and even our common wealth. I believe each of us, at one time or another, pursues true self-reliance in the sense first presented by Ralph Waldo Emerson: to make an independent statement, to be strong, self-assured, to experience reality with originality like the “first man that ever went into a wood,” and to resist, as Emerson says, a “society [that is] everywhere in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members.”

The pursuit of self-reliance must be tempered, however, as I am sure Emerson intended, by our recognition and acceptance of the larger social obligations that we have to our community, our neighbors, and the earth. For just as none of us can be truly self-reliant until all of us are self-reliant, none of us can be food secure until all members of the community are food secure. I cannot rest easy, enjoying the few privileges that my skill and toil may have earned me, knowing that so many of my brothers and sisters struggle on a daily basis for their food, with their health, and against the brutish uncertainties of an indifferent market economy. As my colleague Peter Mann of World Hunger Year has said in reference to the events of September 11th, “A hungry world is indeed a dangerous place. Only when our food policies begin with the hopes and dreams of the urban and rural poor will we build true food security, which will also be a huge step toward homeland security.”

No, those of us who strive for self-reliance are not anti-community, anti-social or even self-indulgent. By seeking to fulfill ourselves individually, we wish like anyone to gain mastery over the skills we need to protect ourselves from threats to our well being and to keep those we love warm, safe, and secure. It is only natural that we wish to attain a level of competency that will strengthen our connection to our land, our food, and our community. Because it may only be through the cultivation of such basic competencies as gardening and farming, food processing and cooking, the operation of small businesses, the exchange of goods and services in local and regional marketplaces, and the practice of civic and political action that we can deter the threat of a global corporatism that is increasingly faceless, placeless, and soul-less.

We need a vision of food security that embraces these core competencies but also makes room at the table for everyone. It should be a vision that closes the divide between our food and ourselves, embraces the principle that we all have the right to food, and supports the opportunity for each and every person to attain self-reliance. A vision is just that, some place in the future that you can imagine more easily than you can see. It’s an idea of sweet and inspiring proportions, but its attainment is nevertheless imaginable. We know it’s there, down the road apiece, but we’re not exactly sure how to get it. We know the direction but not all the steps.

And, above all else, we know the risks of not trying to achieve our vision:

• U.S. Census figures show over 10% of our nation’s households are food insecure;

• Nationwide, according to America’s Second Harvest, we are seeing record numbers of people using food pantries and other emergency food outlets;

• Concentration in the food industry, especially in the processing and retailing sectors, threatens competition, farmers, and even consumers as demonstrated by the control of 80% of the grain market by three corporations;

• Our family farms are threatened by a global food system that sets prices in the global marketplace, which undermines the farmer’s ability to pay costs that are determined locally, i.e., land and labor;

• Six of the leading 10 causes of death in the U.S. are diet related, with diabetes and obesity at all time highs. Rates of these illnesses are often twice as high in low income areas and communities of color as they are in more affluent communities;

• Biotechnology is taking us places that we do not yet know, and are not yet prepared for; and,

• A world of convenience food, fast food, corporate branding, and declining cooking skills threatens to undercut all that we food system activists may yet achieve.

The task before us, therefore, is to create, with our hands, minds, and hearts, in the company of those with skill and spirit as well as with those who may be meager in both, a truly just and sustainable food system. Our task, then, must be the development of a sustainable food system that, at a minimum, includes the following criteria:

• Incorporates social justice issues into a more localized food system;

• Removes barriers to affordable quality food outlets;

• Develops the economic capacity of people to purchase food;

• Trains people to grow, process, prepare, and distribute this food;

• Maintains adequate land (in urban, peri-urban, and rural areas) and growers to produce a high percentage of the locale’s food needs;

• Integrates environmental stewardship info this process; and

• Actively promotes the involvement of every citizen, in other words upholds the democratic process, in every phase of the food system and in all policy arenas that influence our food system.

In other words, sustainable development implies the incorporation of social and environmental issues along with economic ones in the practice of development, a practice that promotes, indeed requires, community participation and civic engagement. This is largely what we mean when we talk about food security, and sustainable agriculture, and community food security. The development of our community’s food system should be conducted in such a way that it produces and distributes food that meets the needs for maintaining optimal health and cultural connections for the entire community while utilizing resources in a manner that doesn’t jeopardize future generations (Hamm, NESAWG Annual Meeting, 1998).

As a community food system practitioner who wants to put these ideas into practice, I would advocate as well for the “3 Ps” – Projects, Partnerships, and Policy.

Projects – Select from the rich smorgasbord of community food activities that can slowly transform our food systems. CSAs, farmers’ markets, farm-to-school projects, anti-hunger advocacy, local food policy councils, food and farm oriented business incubators, wholesale distribution channels controlled by producers, and so on. If you don’t like the menu, create your own dish, but by all means make room for yourself at the table.

Partnerships – Discrete local projects are good, but by themselves they are not enough to transform the food system – and we seek nothing less than a total transformation of our food system. As Edmund Burke said, “It is not only our duty to make the right known, but to make it prevalent.” To go beyond our small projects and communities, in other words to build the self-reliance of the greater whole, we must build alliances, partnerships, and complementary relationships. We must construct a common agenda for change with environmentalists, nutritionists, antihunger advocates, food bankers, local planners, community and neighborhood developers, and policy makers. This can be as modest as connecting some farmers to a food bank or a school system, or as ambitious as developing a city or statewide food system coalition.

One of the greatest obstacles we face in re-localizing our food systems is ourselves. As community organizations and agencies that provide services and want change, we often fail to work together, coordinate our efforts, and avoid duplication. We often lack a venue where we can plan and develop a common agenda. We owe it to our clients, taxpayers, donors, and ourselves to avoid fragmentation, duplication, and poor coordination. If we don’t hang together, we will most certainly hang alone.

Policy – We need the broad shoulders of all levels of government to help us push the food system in the direction we want. Through regulation, government contracts, financial resources, and the public spotlight, we, the citizens, can make a difference. In Hartford we have a local food policy council. We have developed the Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program that connects local farmers and low-income communities. We have developed what we believe is the first state food policy council in the country. Through the efforts of the Hartford Food System and a ragtag band of community food activists from L.A., Texas, and Massachusetts, we formed the Community Food Security Coalition, which persuaded Congress to pass the Community Food Act that now provides $16 million over six years to scores of local ventures, including several here in the state of Maine. Funded projects are now helping recent immigrants in Washington State to learn organic market gardening; teaching low income people in New Orleans how to develop and manage value-added micro-enterprise food projects with the raw material coming from nearby, minority-owned farms; helping a group of Latino gardeners in L.A. start a marketing project; and helping groups in northern New Mexico develop new connections between farmers and low income communities.

The concept of community food security gives both local activists and policy wonks the best framework in which to tackle food system problems. Community food security is an extension of the basic food security concept that we have defined as “all persons in a community having access to culturally acceptable, nutritionally adequate food through local non-emergency sources at all time.” And it uses a holistic approach that attempts to generate multiple benefits by connecting food activities to economic development, job training, environmental protection, urban greening, farmland preservation, and community revitalization.

Our record of achievement over the last few years gives me hope that we will one day realize our vision of a local, sustainable, and just food system. I am inspired daily by the work of thousands of activists around our country, the warriors and builders whose boundless imaginations create alternatives to a global food system. I am inspired by the hundreds of young people I meet every year who come to us as interns, or work for change in their colleges and communities, or take on the toughest foes armed only with their idealism. And I am inspired by each of you and the good and progressive and competent work that you “Mainers” are known for. You have led the way with models of rural economic development, the promotion of locally and sustainably-produced food, and your commitment to social justice.

It gives me hope that not only will we one day prevail, but that we may overcome the real terror that resides within our own borders; for in spite of our progress we have made as a movement, I’m afraid that the greatest challenges are yet to come. The grinding of a man’s spirit under the corporatism of modern life and the exigencies of the free market threaten to rob us of our freedom like no terrorist ever could. We will be branded and “market-niched,” calibrated and concentrated until all the juice of our humanity is squeezed from us. The greatest test of our resistance will be how we oppose the insidious force of a global food system that creeps in on cat’s paws, a global food system that cynically suggests that without bioengineering we will not be able to save a hungry world from starvation, and a global food industry that veils its deeds in trinkets and beads given to the malnourished and their representatives.

We will be sorely tested to preserve our humanity in the face of this quiet terror, the real terror; the one that truly threatens the security of our communities. As we gird our national loins to fight the terrorism that allegedly exists in the most faraway and destitute places on earth, let us remember the wars at home that we have not yet won, let alone begun to fight. The face of terror does not always have a beard or cover its head in a turban. For me the face of terror is still found in my own back yard. I see it in the eyes of a hungry child, in the face of the family farmer watching his livelihood placed on the auction block, in our downtowns pillaged by big-box stores and fast-food strips coiled menacingly on the edge of town, or in the contour of our sacred land despoiled by carelessness and greed. I must question our leaders who claim that escalating military budgets, overzealous security precautions, and the abridgement of our civil liberties are indeed for our own good. It becomes increasingly obvious that our actions abroad and measures domestically are a pretended form of patriotism that simply cloaks our self-interests. As Samuel Johnson once said, “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.”

We have in this room today a powerful antidote to this miserable constriction of human possibilities laid before us by our leaders. We can reset the terms of the debate by once again placing the concerns of social justice and environmental sustainability squarely on the table – our table, the one we set with the utensils of democracy, inclusiveness, and diversity. We can feed our imaginations with the fury of each other’s hopes and ideas and, in so doing, expose a rich gene pool of talent, expertise, and wisdom. Perhaps we are more like a garden, which as Michael Pollan has so eloquently described in The Botany of Desire, “is a place of many sacraments,” a place where no single species dominates, and where the imagination can be refreshed and re-ignited.

The measure of our success will be in the number and types of people gathered around our table. They will share familiar words and phrases passed like baskets of bread from one guest to the next. The measure of our success will be found at town meetings and board meetings where food and farms appear on the agendas as regularly as they do on the menus of local restaurants; in the gentle exchanges of teacher and student in the classrooms where place, and food, and health, and the sway of seasons are woven through the daily lesson plan. Articles in local papers about people, farms, and food will be the common currency of our communication. The measure of our success will be gauged in the distance shortened between ourselves, our land, and its sustenance. For when we reduce that distance, we reduce our alienation from farmers, from nature, and from self; we make the parts whole and gain confidence in ourselves. Our success in rebuilding local food systems will be measured as much by the growth in our individual civic competencies as it is in the way we master the crafts of food production, cooking, or education. The measure of our success, in other words, will be revealed in our speech, our writings, and the leadership we bring to our cause. We will measure our progress in the courage to speak our minds; to stand before a zoning board and say ‘No’ to the latest manifestation of global corporatism, and to wrestle for resources that will make our communities whole.

There is yet another measure of success that we must aim for, and that is the obligation that we all must share to leave no one behind. When it comes to ensuring the health and nutrition of each person and the food security of each household, we start with the community, and who is the community but you, and I, and our neighbors. I have felt from time to time that our movement’s hunger for good local food and our commitment to sustainability are no more than the pursuit of lifestyle over substance. We may, with the best of intentions, seek the good life without noticing that the lives of others decline or stagnate. And when we do reach out to the food insecure, too often we offer only charity, but forego the much more difficult task of building self-reliance. Just as we work to eliminate the distance between ourselves and our food, between the city and the country, and between the producer and the consumer, we must seek to end the social distance between all of us. The divides of class, race, and income cut like a knife through the body of our communities.

But through food, through building local food systems that build local self-reliance, by addressing suffering and injustice in our own back yards, as well as through the resources we can glean from government, I believe we can turn these forces around.

I turn in conclusion to the voices of two women whose words may help to light the path. Whether they like it or not, women are the nurturers whose gentle wisdom always holds its ground against the gusts of male bravado. Or it may be that as Jim Hightower says, “It’s the rooster that crows, but it’s the hen that delivers the goods.” The first woman is Rachel Carson, who warned us of the deafening possibilities of a Silent Spring, but reminded us as well of the exhilaration and beauty to be found when “we place ourselves under the influence … of so small a thing as the mystery of a growing seed.” Shirley Chisholm, the second woman, was the first African American woman elected to Congress. In 1969, at the height of our national insanity over the Vietnam War, she was one of the first members of that august body to speak out against increasing military spending, which was being financed by cuts in social programs. She asked why on the same day that President Nixon had announced that America would not be safe unless it developed a defense system against missiles, funding for the Head Start program was slashed. She said that “unless we start to fight and defeat the enemies of poverty and racism in our own country and make our talk of equality and opportunity ring true, we are exposed as hypocrites in the eyes of the world when we talk about making other people free.”

These seem like apt lessons for this day and age; that we can find common cause in the appreciation and protection of the environment and beauty while working undaunted to end food insecurity and poverty. And to do both when the national consciousness is distracted by threats of an uncertain and poorly defined nature.

Whenever our nation raises its sword, a behavior that we repeat with an all too disturbing frequency, then those who are most vulnerable – the poor, the elderly, the mentally ill, women and children – are always forced to the end of the line. Whenever we label someone or something as “our enemy,” a description that all too conveniently reduces all in its path to subhuman status, then license is automatically granted to trample the earth and abuse its resources. We must resist these temptations because we instinctively know where the threats to and opportunities for security lie. They are the roots that run through our soil and communities and entangle us in a mutually fulfilling web of obligations. They give us the time and space, indeed that necessary sense of leisure, to stare in contemplative awe at the mystery of the seed and to taste “what by all together in nature is pronounced the sacred world.” (John Tagliabue, Collected Poems)

Our real security and the sustainability of all that is necessary to human survival will be measured by how well we nurture those roots. There is no better place to perform that sacred act than with our food system – to build its productive capacity and health, to strengthen the means of exchange and the viability of livelihoods, to nurture the self-reliance of people and communities, and to give each and every one a seat at the table.

Thank you for giving me this chance to speak with you and I wish you all the very best.

Mark founded the Hartford Food System, 509 Wethersfield Ave., Hartford, CT 06114, an organization that connects low-income people with farmers in the surrounding community. You can email him at [email protected].

Questions & Answers

Q. What is the Hartford Food System doing now?

Winne responded that the organization has a 20-acre CSA farm in its ninth season. A little more than half of the food goes to subscribers; the rest (120,000 to 130,000 pounds of organic fruits and vegetables per year) goes to local people who need it.

The organization is engaged in a number of policy initiatives. It is trying to increase the use of local vendors by the city in its summer food program. (About 45% of the children in Hartford are at or below the poverty level.) At the state level, it is promoting farmers’ markets and farmers’ market nutrition programs, ensuring that they are connected to low income communities and to farmers. The group is launching a farm roadmap that highlights farms that sell directly to consumers.

The group also is publicizing the unhealthful consequences of having fast food restaurants in or near low-income communities. Winne believes that the city of Hartford puts too much emphasis on bringing in businesses such as fast food restaurants, without considering the consequences.

Q. How do you staff your CSA?

The farm has a full-time farmer and an assistant farm manager. Interns are hired over the course of the season. The farm “is pretty much breaking even, including all of the salary, fringe benefits ….” The books don’t include the social overhead – teaching people about food and farming. Inner-city kids spend time on the farm learning about farming, cooking, and so on, said Winne. Sometimes these kids go to a Senior Center and show the seniors how to cook food that was raised on the farm. The organization receives grants for such programs.

Q. Do you have a curriculum?

They have lesson plans that were picked from dozens of curricula. “We have over the years worked more directly with schools,” said Winne. “Now we’re more involved with kids coming to our farm.”

Q. Is the food that is given away included in the social costs?

That food is not entirely given away. Organizations buy that food but pay about 20% of what a regular CSA customer does. Their CSA is based on the Food Bank model in Western Massachusetts. (See the March-May issue of The MOF&G.) “We wanted to engage the community more directly in production and distribution” of the food, said Winne. “People are not out there actually doing the farming, but they’re involved. We didn’t want to just give the food away.” *

Q. What are the feelings of the middle and high income people who are members of your CSA about the food that is sold for less to organizations?

The CSA customers are getting as much as or more than they would at the local wholesale store for their dollar. Third or fourth on their list is the social effect of the farm. Their core interest is quality food.

Q. Do the organizations that get your food preserve it in any way? When we gave fresh produce to food pantries or soup kitchens, they didn’t always know how to cook or preserve it We offered classes, but they weren’t popular.

This is something the organization would like to do more, but does not have time for now. They have done cooking and preservation classes as a “fun thing” with the young and elderly together. This contributed more of a social and educational benefit than a benefit toward long-term food security.

Q. We are working at a fairly small level now regarding food security. What efforts can take us further?

A long-term strategy has already been going on for 10 or 20 years. “We may actually see something tremendous happen before we die. That’s what I’m holding out for,” said Winne. He reiterated that working at the local level – with school boards, at town meetings – to raise these issues Is important. “A lot of us don’t do this.” Also, he suggested building broader alliances. “More and more groups are now willing to work with proponents of sustainable agriculture.” A farmland preservation program in Connecticut, for example, involves about 100 organizations, only a few of which are concerned directly with farming. Groups that wanted to save birds, preserve farmland, maintain the rural landscape, and so on, all came together. “Politically this is very effective,” said Winne. “You need a focus … to say, ‘This is what we care about.’ You’d be surprised how many groups will jump on the bandwagon.”

Q. Have you had success at bringing people from the health care industry into these discussions?

“That’s been slow,” said Winne. He related speaking to a group of residents at a hospital at lunchtime. “You wouldn’t believe how many bags of McDonalds, Kentucky Fried Chicken … [how many] large Cokes … I said, ‘Gee, folks, don’t you know what this Is about?’ It was challenging … There were some weight problems there. But there are friends out there. You might have to seek them out individually.”

Obesity, Winne continued, is creating all kinds of medical problems, but it’s finally getting recognition as well. “I think fast food is going to be the next tobacco,” he said. “I think we’ll see some of the same remedies.”

Q. Do you think the Slow Food Movement might draw the doctors in?

“I have a bit of a quibble with the slow food groups in our area,” Winne responded. “They’ve become sort of a gourmet eating club. That’s not what it started as.” However, his wife is a chef, and her expertise has helped get restaurants to feature more and more local food. “When we have meetings or conferences, we try very hard to get local food, to bring in chefs …. We talk about local food.” He said that the Iowa Farm Bureau just put local food in its cafeteria. This kind of effort “has tremendous ripple effects.”

Q. There’s almost an insoluble tension between food security – shortening the distance from the farm to the table – and the corporate system to move right in, brand it and market it. And the corporations co-opt food. In the late 70s in the Camden area, 800 households were in a food coop. It was so successful that stores noticed and improved their produce sections, brought in more local food … and people got too busy with their jobs and lives, so it was easier [to go to the store] and buy food. In Southern Maine, Fresh Samantha’s had such a good product that it merged with a California company, and both got bought by Coca Cola.

Winne said that he wasn’t sure he had an answer for this problem. “Chances are we aren’t going to get rid of those folks. Where do we have control?” He suggested working, for example, with colleges, which can buy some local food. Changing the purchasing contracts and bidding procedures at the state level is another possibility. “I’m very concerned about the power of the marketplace,” he said. He suggested that “as citizens, students, employees, [we] do what we can to support the local system and not do any harm to it. I’m impressed with what’s going on at colleges. More and more students are concerned with where their food is coming from.”

Winne concluded by saying that he is concerned about the desire people have for organic over local. “If we keep talking organic and deal with huge organic producers in the West, we’re wiping out the smaller producers in New England. I’m seeing that a lot. We need to educate people about local foods.”

– Jean English