|

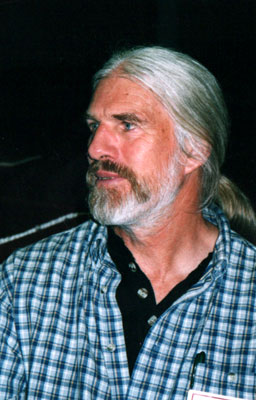

| Steve Gilman was a featured speaker at the Farmer to Farmer Conference last November. English photo. |

The basis for terms such as “whole farm systems” and “holistic management” is the simple ecological concept that everything is connected with everything else, says organic grower Steve Gilman. “We live with this [concept] everyday. We know what it means. But, because of the nature of what we’re up against, sometimes we end up having to focus” on a pest problem, or on getting a crop out. In that focusing, says Gilman, we can end up excluding many things and losing track of that ecological concept.

Gilman, who cultivates 15 of the 47 acres on his Ruckytucks Farm in Stillwater, N.Y., was the Farmer in the Spotlight at MOFGA’s Farmer to Farmer Conference in November. He explained that ‘Ruckytucks’ are parallel, 10-foot-high cliffs – “amazing structures” – on fault lines that snake about 100 yards apart along the hillside beyond his farm. Gilman grows vegetables and herbs to sell to restaurants and to CSA members. He is a long-term member of NOFA-New York and is on the NOFA Interstate Council. He has served on the Northeast Region Administrative Council of the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program as well.

Gilman understands how farmers can lose track of the ecology of their farms, and explained that scientists have an even harder time “because they’re rigorously trained to control everything but what they’re studying to get a cause and effect. A lot of times those causes and effects work well in the lab, but in the field a whole lot of other things are going on.”

One of the main differences between organic farmers and those practicing IPM or sustainable but nonorganic farming, continued Gilman, is that “organic farmers probably make the most of that ecological concept – primarily by using biological control methods. This is a broad statement,” he acknowledged, but “to me, the basis of the whole farm ecology is the health of the soil – that drives everything else. An unbalanced soil will cause insect, weed and disease problems quicker than anything else, and if you want to solve these problems, you can get out the pesticides and create further problems, or you can address the imbalances. And I think the soil is a primary source of imbalances.” These imbalances can occur not only in soil fertility, but in soil structure as well.

“One of the problems with being an IPM or sustainable farmer is the tendency to reach for the solution – the rescue remedy – it could be chemical, it could be biological, it could be transgenic – when a problem comes up. Each use of these things can set the whole system back. Organic systems don’t do that,” said Gilman. Some of the older pest controls, such as rotenone, were toxic, he admits. “You’ve got to wear a mask.” However, they are shorter lived in the field. Now this difference is seen in relation to Bacillus thuringiensis: When applied in an organic system, this biological insecticide has a two- to three-day life in the field, but when engineered into a crop, it lasts more than eight months after the crop is harvested. “The minute you start creating more of a full-time presence of a toxin in the environment, then there [will] be a lot of nontargeted side effects.

|

| Biostrips are “starter cultures” of beneficial organisms before crops are planted. Photo courtesy of Steve Gilman. |

|

| Biostrips and beds of Alliums. Photo courtesy of Steve Gilman. |

“There’s also a concept called secondary pest production. In this scenario, when you intervene, you knock out beneficials that might have controlled other pest problems. Now that the beneficial is no longer in place, all the potential pests are free to come forth. Those are the secondary pests. Maybe that spined soldier bug would have taken care of the Colorado potato beetle; it might have controlled some other pest problems you had” as well.

The Biostrip Method

To create balance on his farm, Gilman has established permanent beds with “biostrips” growing between them. He originally established permanent beds to minimize soil compaction by setting his tractor wheels so that they straddle the 52-inch-wide beds that are sized by his Kuhn rotovator. “There’s not even a footprint on my beds anymore,” he said. These are not raised beds per se, but are raised by virtue of having organic matter added repeatedly, and by being fluffed up relative to the pathways when the beds are cultivated and when cover crops are tilled in. One benefit of these beds is that by being slightly raised and by having good soil structure and drainage, they warm up earlier. Gilman’s upstate New York farm in the shadow of the Adirondacks is in zone 5, almost 4, so his frost-free season lasts only from about May 31 to September fifteenth. For a long time, Gilman was keeping the pathways between the beds clear, but once, when he got behind in his work, vegetation started growing in the pathways. To control it, he mowed it periodically. He developed a strategy where he wouldn’t mow and blow the sod clippings onto tender crops, such as lettuce; instead he would mow and blow the clippings before planting that crop. If he had just planted tomatoes, however, he could actually generate 3 to 4 inches of a grass mulch for them by mowing up one side of the bed and down the other and blowing the clippings from the 28-inch paths onto the bed. His heavy duty TroyBuilt rotary mower with self-propelled rear wheels thus saved him time.

Having sod between the beds was just so “nice after a rain” – his boots stayed clean, and the biostrip vegetation helped get rid of excess water, especially in the spring. Also, when CSA members came to the farm, they easily obeyed the only rule: ‘Please walk on the grass.’ “Kids get it, even my dogs get it after a few times of pulling them out of the beds,” said Gilman. The biostrips “bring an order to the farm.”

Next he let the sod strips grow up to “the wildflower of the week or month.” At times in the spring, if you look across the beds, “all you see is golden dandelions. It’s awesome. It’s hard to see the beds. Dandelions are one of the first pollen/nectar sources during the whole growing season. Some researcher found 93 different species of insects that feed on that pollen/nectar. The preponderance of those was beneficial insects.”

|

| Beds of lettuce with biostrips alongside. The plywood in the forefront is used to mark spaces where the lettuce will be intensively planted. Photo courtesy of Steve Gilman. |

So, the biostrips had become convenient by providing mulch, keeping boots clean, aiding drainage, and keeping the farm orderly; they minimized soil compaction; and they were producing food for beneficials – “breeding up large sources of beneficials – more than would normally be in the area, because [the biostrips] were providing room and board above and below ground – not only pollen and nectar, but habitat.” Those beneficials, Gilman added, “don’t thrive on black plastic.” He mentioned a Hampshire College study in which eggplant growing on black plastic got off to a nice early start, but by midseason it was “loaded with Colorado potato beetles.” When the researchers used a straw mulch instead of plastic, they saw more beneficials. Now they’re trying biostrips. “They’re finding that if you can provide more of a natural habitat, it gives a place for these critters [beneficials] to hide, breed, hang out, lurk. It isn’t just like clean rows of crops, come and get it, with occasional beneficials working in their midst. This is literally a jungle.” Biostrips, he reiterated, “bring habitat for beneficials right into the field between the raised beds.”

To maintain that jungle, Gilman never mows “real tight. It doesn’t look like a lawn when I’m done.” Over the years Giiman learned that he had to get rid of problem weeds such as quackgrass and thistles before establishing his biostrips so that they wouldn’t grow into the beds. “It really pays to have thorough cultivation schemes to get annual weeds and nasty perennials under control.” Even now, if a weed is threatening to become a problem, he won’t hesitate to implement a weed control cultivation and cover cropping scheme and then re-establish the beds and biostrips.

He also learned that he could encourage certain species in the biostrips. “Dutch white clover is a real good one.” Although the seed is expensive, the plant “stands shading, compaction from tractor tires, blossoms several times per year, spreads by stolons; it is a legume, so you get a nitrogen source in the biostrips that is a way of feeding the biostrips – I never fertilize them.”

Hard red fescue, used by orchardists, is another favorite. “It goes dormant in the middle of the season. Sometimes you have to look out for those competition scenarios. I don’t want a huge green mass growing among my crops that could potentially drain my water supply. On the other hand, there is another factor going on in terms of what water is about. Having fescue helps – All of a sudden you’ve got kind of a dead mass of grasses among the wildflowers coming up, so you don’t have such vigorous growth.”

He likes the wild species that come up because “they’re survivors. A lot go down, down, not just to 6 inches. They’re well connected to the water table as it drops. They act as hydraulic pumps. A lot of times you can maintain an upward water pressure” with them. “With crops, a lot of times the water table drops too far below the reach of the crop roots, and the crop goes into shock because it really doesn’t have a water supply. That doesn’t happen in sod crops as readily. If you can provide a little upward hydraulic pressure, the beds – particularly since they’re planted a little closer together than normal, with a higher crop plant density – it really seems to keep the whole field watered. I apply irrigation if I have to, but there also seems to be an overall beneficial effect” of biostrips on soil-water relations. “So the biostrips aren’t really competitive that way.”

One of these wild survivor plants is Queen Anne’s lace. “This composite of tiny flowers is particularly conducive to the small mouthparts of wild pollinators,” said Gilman, so he usually mows it after flowering ends but before it goes to seed and becomes a weed in the beds. However, it can be a vector for aster yellows – a virus that can infect lettuce – “so I keep Queen Anne’s lace near the lettuce beds mowed before it goes to flower. There are incompatibilities” in the biostrip method, which “is just at the beginning stages” of study. Two resources that he recommended are Enhancing Biological Control by Robert Bugg; and the website www.ATTRA.com, which has a paper on phenology – “what flowers when, where, what beneficials feed off of them” in different sites in the country.

|

| Gilman’s greenhouse and cold frames. Photo courtesy of Steve Gilman. |

Beyond the Biostrip

Another rule of an ecological approach to farming, said Gilman, is that health and strength come through plant diversity, through insect diversity and through ecological diversity. Hence, he looks at his whole farm, not just the biostrips, as part of that “jungle” for beneficials. He has lots of birdhouses, for instance. He leaves wild areas around the farm, and he grows flowering plants that attract beneficials. In one wild area, crown vetch, yellow sweet clover, and about five other kinds of clover have seeded themselves. A favorite for more formal plantings is the annual Tithonia, or Mexican sunflower, which is “a primary habitat plant for butterflies, which are pollinators. It will get up to 6 feet tall and it’s totally covered with orange blossoms.” He likes to plant it every year along the fringes of his cultivated beds.

Giiman recommended planting corn “even if you’re not going to eat it,” because “it’s such a pollen producer, such an insectary plant – for that reason alone, it’s worth growing. For them to say Bt corn doesn’t affect Monarchs and other beneficial insects,” he admonished, “is ridiculous.

“We’re talking overall habitat,” he added. “Holistic organics has a lot to do with permaculture.” The beds are permanent, and a lot of plantings are perennial. He recommends the ATTRA website again for its “Farmscaping” article. “We’ve all heard of edible landscaping – shrubs that produce food that you can eat. Why not plant shrubs that produce food that beneficials can eat?” He sees the wild roses that grow along the roadside by his farm not just as beautiful flowers but as pollen/nectar sources, as part of the whole farm habitat.

“I also grow a lot of cover crops,” continues Giiman. He likes to plant buckwheat and let it “go to full flower before knocking it down. You can let it go to seed if you want to grow another crop, but you can develop a real weed problem that way.” In addition to being an excellent nectar source, buckwheat smothers weeds and sequesters phosphorus that would otherwise be unavailable for succeeding crop plants. “You can prepare fields with cover crops before preparing biostrips and planting beds,” said Gilman.

“I like to grow cowpeas,” he continued – “a beautiful summer annual legume, particularly in dry years. It’s an African hard pea, or pigeon pea. It gets up to 2 to 3 feet tall, and its taproot busts through a hard clay layer and promotes drainage over time. It also has a nice network of fine roots at the surface, so it can take advantage of a heavy dew or light rain, but it’s also plugged in deeper.” He tried planting buckwheat and cowpeas together, but “it didn’t work out.”

Annual ryegrass is planted when space opens up, because “I hate to see bare soil.” Many beds get oats over winter – all sown by hand. “People have been sowing seeds for eons” by hand, says Gilman. “I can sow a bed in two minutes and it’s done.” The oats “grow right until Christmas.” Other beds, such as those that will be planted to corn and tomatoes the following spring, get hairy vetch and oats. The vetch is either rotovated into the soil in the spring, or it’s scalp killed – mowed very close to the ground so that the growing point is cut – and left on the soil as a mulch. Gilman said that this nitrogen-fixing legume is “beautiful before tomatoes. There’s a real affinity.”

The Mycorrhizal Connection

Another consideration regarding whole farms is what’s going on in the soil. When Gilman gave farm tours, he delighted in digging up a teaspoon of topsoil and asking schoolchildren how many organisms are in it. “They started in the hundreds. I kept telling them to go higher and higher and higher. It was the kid who guessed in the billions who was right! And it blew their minds. And it blows my mind. Microorganisms in the soil are being colonized by the crop plant. Sixty percent of the crop’s photosynthesized energy is not going into crop production, it’s going into root exudates. It’s going down through the plant, out through the roots, into the soil to feed these beneficials. These, in turn, are the ‘translators’ – They are mineralizing the nutrients from stones, rocks and the mineral content of your soil.”

Among those microorganisms are mycorrhizal fungi – beneficial fungi that associate with plant roots. “It turns out that dandelions are mycorrhizal,” said Giiman. “They are an overwintering habitat for mycorrhizal fungi.

“A lot of crops are bred to grow fast and have small, compact root systems,” he continued; “to grow a harvestable crop fast, not to spend time putting out an extensive root base. They feed only in the top 6 inches of the soil, with maybe a few stability roots to help out. If this crop plant can link up with mycorrhizae, then it has access to these pipelines, the hyphae, that extend out into the soil and go down to the water table. As the water table drops over the summer, the hyphae keep going. They can pump water back up to that crop plant.”

They can also bring nutrients to crop plants. While soils usually contain plenty of phosphorus, for example, much of it is in chemical forms that are unavailable to crop plants. Mycorrhizae, however, secrete enzymes that “grab ahold” of that phosphorus and “pump it back through the pipeline and into the crop plant. That crop is totally connected with the soil food web.”

While conventional agriculture regards soil as “the thing that holds the crop up while you apply everything it needs to grow,” organic farmers are adding to their awe of the soil as they are beginning to see how the soil food web works. “I think it’s our job as farmers to look at these relationships and understand what’s going on,” said Gilman. Clean cultivation starves out these fungal relationships in favor of bacterial associations, while biostrips and/or periodically planting a field to a sod crop re-establish mycorrhizae.

Bacterial associations aren’t all bad, Gilman explained, because bacteria mineralize nutrients too, but fungi are desirable as well because they associate with and thus extend the root systems of crop plants. Forest soil, with the slow decomposition of leaves and broken branches, is almost completely dominated by fungal associations. “The decomposers that do that job are fungi.” Thus you can bring these fungi into your farm soil not just through biostrips, but by making and applying compost from the small branches of trees and shrubs as well. This “ramial chipped wood” is “a beautiful composting source. There’s not too much cellulose and lignin to be broken down. It decomposes pretty quickly, and its C:N ratio is fine.”

Gilman sees the mowed grass, herbs and wild plants that he blows onto his beds as “a forage crop for soil livestock. Those billions of critters in that teaspoon of soil can eat that. And once a bed gets planted, the mycorrhizae can really spread fast and colonize a bed. The mycorrhizae that overwinter in the biostrip can repopulate the beds in between in fairly short order. It’s like a yogurt starter in the field the whole time, and when my beds are cultivated, prepped, ready to plant, they [the starter microorganisms] go to work.” He theorizes that colonization by beneficial organisms may keep plant diseases at bay the same way the beneficial bacteria in yogurt occupy sites in the human digestive tract, and the way beneficial bacteria live on human skin, so that harmful bacteria can’t “get a toehold.”

Lettuce Culture

One of Gilman’s main crops is lettuce, including French Batavian, looseleaf varieties, some Romanies and a small variety, Diamond Gem. The plants are started in Speedling containers, with 1 x 1-inch openings at the top, a 2-inch deep pyramid, and a 1/4- x 1/4-inch opening at the bottom. The Speedlings sit on sticks so that any roots that emerge through the bottom opening are air pruned. This creates a plant with a myriad of secondary and tertiary filamentous roots that is “ready to go when it’s put into the ground.” The seedlings of most varieties spend three weeks in the greenhouse, one week in a coldframe, then the plants grow for four weeks in the bed. Each Speedling container has 200 cells, so Gilman grows four Speedlings of lettuce per 100-foot bed. “I can easily double my plantings for a specific weekend,” he said, “when I know there will be a big demand for lettuce.” Those weekends include a big day at the local racetrack and Parents’ Day at Skidmore College. “If you’ve got it, you can sell it, so I make sure to have it. I’ve been here 25 years; I know my market really well.”

He grows the crop 6 inches apart in both directions, with six plants across his bed. The spacing is controlled by marking the bed with a “gridder” – a 4- x 6-foot sheet of plywood with bolts coming through it every six inches, held in place by nuts, and with handles on either side. He can walk along the biostrip, swing the grid into place and step on it, and it leaves an imprint where each plant will be grown. The plywood “presses the soil just a little bit” and opens a hole. He still has to open the hole a little more with his fingers, but his Speedling plants are easily set in place this way.

Gilman makes sure his lettuce gets an inch of water each week once it’s in the field. He has a farm pond to supplement rainfall. The 73-acre, 10-foot-deep pond has steep sides to prevent algal growth. He pumps water into 2-inch lines and drags hoses around to his beds, delivering the irrigation water through Rainbird sprinklers.

When the plants mature, they cover the bed. “You can get a heavy rain and it won’t even get dirt splashed up on the leaves,” he says. As he harvests the crop, he dips each head into a 5-gallon bucket of well water and immediately puts any trimmed leaves into another 5-gallon bucket. These trimmings “go right into the compost. They’re not lying on the soil, they’re not spreading disease, not creating problems for me.” The washed heads are packed right away, 24 heads into each plastic bag, and these bags are delivered right into coolers at restaurants. “They’re good sized, full heads,” says Gilman. “If the restaurant doesn’t use them right away, the plastic keeps in the moisture.”

He finds that by rotating (never growing the same crop family in the same place in fewer than three years), practicing sanitation and having his beds aligned with the air flow, he can break a lot of pest cycles. After a bed of lettuce is harvested, Gilman mows the biostrips on either side of it, blowing the clippings onto the bed before planting another crop.

Some growers at Farmer to Farmer questioned the close spacing of lettuce on Gilman’s farm. Gilman said that he would go to a wider spacing if he had disease problems, but in their absence, he likes his system: It results in more compact, upright plants that are damaged less when cut. Grower Jason Kafka suggested that, if disease were a problem, the 6-inch spacing could be used and alternate plants could be harvested early to enable the remaining plants more room and sufficient air movement as they mature.

When asked about spacing for other crops, Gilman said that he grows two rows of corn, three of broccoli and two of potatoes on his beds.

To extend the season for growing spinach, he puts Rebar hoops over the beds and covers them with 10-foot-wide construction poly. These mini-greenhouses are cheaper than hoop houses. The plastic can be taken off during the day.

Pests

When asked about pests, Gilman said that he avoids some by not growing crops they attack. He does not grow strawberries, for example, partly to minimize tarnished plant bug populations, but also because he’s busy mowing his biostrips in the spring. Likewise, he doesn’t grow crops that attract flea beetles, although he thinks that this pest might be controlled by planting a crop such as canola, which attracts flea beetles, and treating the soil there heavily with parasitic nematodes, then following with a crop plant that is susceptible to flea beetles. The few Colorado potato beetles that populate his plants are shaken out of the crop as Gilman drives through the field and some old VW metal fenders, attached upside-down to his tractor, shake the plants. The beetles drop into the fenders and are then discarded.

When Farmer to Farmer participants asked about cabbage maggot control, Eric Sideman said that planting after forsythia flowers can minimize problems with this pest. “There’s a giant population explosion from the overwintering population if you plant before the forsythia blooms.” Other growers said, however, that they had season-long problems with this pest. Sideman recommended that they use row covers.

In response to using forsythia as an indicator, Gilman said, “There’s no better indicator of degree days than flowering plants.” He added that New York researchers have related cabbage maggot populations to the flowering of various plants throughout the season. Regarding soil fertility and soil testing, Gilman keeps track of his beds using spreadsheets. Cover crops are built into his rotations for weed control and for fertility, and clippings from the biostrips add fertility. “If I start to get growth problems or weed problems, it’s time to do something with that bed.”

Compost is also used to add nutrients, but he sees it as more important for disease suppression. He has been making a compost from milfoil that is harvested from Saratoga lake and finds that it is a perfect complement for his clay soil – and that, being an aquatic weed, it has no weed seeds that will grow on land. Unfortunately, someone tried to control the weed by applying an aquatic herbicide to the lake last year, so Gilman won’t be making milfoil compost now.

Asked how he gets reliable soil tests with so many individualized beds, Gilman answered that he’s “really interested in percent organic matter” and tests his soil only every four or five years. “I’m really trying to learn to let nature let me know” when a bed needs added fertility. He occasionally uses ProGrow from North Country Organics “to beef up greens that need it.”

Solar Greenhouse

Gilman has a solar greenhouse with front vents, ceiling vents and a solar chimney. The chimney is based on a design used in the ’20s. “The concept is that heat rises: If you provide a stack, then you create a draft so that smoke doesn’t back up in your house. If you put a wind turbine on top [of the stack], you create a vortex that actually sucks the heat out. It’s really whipping around when it’s sunny. In the winter I can close all the other vents” and the solar chimney is sufficient for ventilation. Gilman did put a fan in when he built the greenhouse, but never needed to hook it up.

Trust

“One of the things I’ve learned to do, and it’s taken a number of years,” Gilman said, “is to trust. I think that’s kind of the main difference between an IPM and an organic approach. The thresholds set up for intervention for IPM pest controls don’t hold true for organic systems, because there are so many beneficials in place all the time that even if you do get a brief spike in any particular pest, chances are you’ve got a beneficial in place that is going to take care of it.

“I’m working on the theory,” he concluded, “that it takes about seven years of organic management to get a balance. You may have outbreaks of cabbage worms, et cetera, at first, but over time, the diversity is increased and pest pressure is reduced. It’s actually good to have some pests around – something for the predators to eat. It’s the opposite of the conventional approach, where [in conventional agriculture] over time there is a buildup of pests and you’re working against nature instead of being one with nature.”

Gilman has taken the last year off from farming in order to write a book called Holistic Organics about his theories and practices. It will be published by Chelsea Green this fall. You can contact Gilman at 130 Ruckytucks Rd., Stillwater NY 12170, 518-583-4613; [email protected].

– Jean English