|

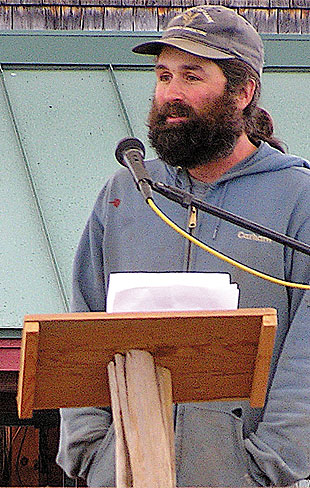

| In his Common Ground keynote speech, Mark Guzzi described the days and seasons on his Peacemeal Farm and his efforts not to feed the world, but “just” to feed his friends, family and community. English photo. |

By Mark Guzzi

One of the region’s most successful young farmers, Mark Guzzi has been growing and direct marketing produce through farmers’ markets since 1993, when he started working on farms. A former MOFGA apprentice and a 2000 graduate of the University of Maine Sustainable Agriculture program, Guzzi now owns Peacemeal Farm in Dixmont, one of the area’s oldest organic farms, which he bought in 2003 from farm co-founder Ariel Wilcox. Along with his wife, Marcia Ferry, and their crew, he grows 10 acres of MOFGA-certified organic vegetables, which they sell at six markets a week – in Orono, Camden, Belfast and Waterville. They also have a booth every year in the Farmers’ Market at MOFGA’s Common Ground Country Fair. An avid believer in the value of diverse and successful farmers’ markets, Guzzi chairs the Orono market, where he’s been a member since 1997. He gave the Sept. 27, 2009, keynote speech at the Fair.

I got home from market yesterday and after unloading the truck and eating lunch, I took a walk around the farm to get some inspiration for this talk. I walked through some knee-high oats, fall cover crop; walked through fall spinach that came up beautifully and then mostly died – I don’t know why; noticed that the hard freeze last night had completely killed the galinsoga and the pigweed but not the lambsquarters – wasn’t harmed at all.

Walked down to the fall storage crops and beets, along the hedgerow where all summer long a marsh hawk would sit on a branch while I was doing tractor work out there and watch me. Normally marsh hawks won’t perch, but this marsh hawk would let me get within 20 feet of him and just watch me the whole time that I was down there.

The beets took quite a beating from the frost, and we’re definitely done bunching beets, but that’s all right because we had a good run of bunch beets.

Then I walked over to Ben Loch [the neighbor’s farm, where Guzzi rents land]. The warm autumn sun was on my back … a cloud of bugs that I didn’t recognize, and a little dragonfly darting back and forth, snatching them up for what surely must be one of its last suppers.

Putting Disasters in the Past

Well, the last Sun Golds have been harvested, and we’ve had a good hard frost at the farm, and for me that pretty much means the end of summer. Finally. I think that one word could pretty much sum up this summer for many vegetable farmers, and that would be “disaster.”

It started out nice and warm and dry, and we got a good start in April and May. And then late May we had one of the hardest frosts we have seen for a while. Even the cold-hardy crops such as peas and broccoli got damaged from it.

Soon after that the rain started and didn’t seem to let up for almost two months.

As if all that wasn’t enough, late blight started spreading – the plague – from farm to farm … other diseases, insects, and of course weeds, which, any of you who know my farm know that it’s quite weedy, and in a season like this, almost impossible to keep control. But somehow or other we survived and while some crops did very poorly, others thrived.

Amazingly enough we had a bumper tomato crop this season and hardly had a single fruit with a late blight infection.

At this point all of that’s in the past. I’m ready to forget about this summer, and we’re looking forward to a good harvest of fall storage crops, and winter, and then next season.

A Year in the Life

The life of a vegetable farmer is truly dictated by the weather and the seasons. Starting in the winter we attend conferences, socialize and network, learn new growing techniques and just generally expand our knowledge. We pore over seed catalogs, put in orders for thousands of dollars of seeds and supplies. There are always endless projects that need attention, but it seems that just selling the rest of the storage crops and getting ready for next year is hard enough every winter.

Before you know it, March comes and it’s time to fire up the greenhouses. Even though the outside temperatures still go well below freezing and we’re still bound to get some record snows, the work in the greenhouse is a good opportunity to get back into the groove of things, and, I always like to say, work on our preseason tan.

Before you know it the snow is receding from the fields and the frost is leaving the ground.

The driveway gets a little squishy.

The first robins are fluttering around on the bare patches underneath the trees.

We should be working on our equipment rather than waiting until the day when we need to use it, but usually we don’t.

There’s really nothing like, for me at least, that first day of getting on the ground to start planting. It’s been a whole year since I’ve done that, and the madness is about to begin again. It’s important for us as mixed vegetable farmers to take advantage of every opportunity that we get to work the ground and plant, especially in the spring. Usually in Maine it will dry out sometime in April and then it’s likely to get wet again, and you never know how long that wet’s going to last.

So for each dry period that we get, we try to till up as much land as we can and start planting. First the peas, other cool-season crops, cover crops, onions, potatoes, leeks, cabbage, broccoli, more mixed vegetables. Toward mid-May we’re starting to get ready for the bigger summer plantings. The greenhouse is usually bursting at the seams, waiting for the weather to settle and for the ground to warm up.

Our season’s relatively short up here, but the days of June are long, and the more we can get in the ground, take advantage of those long days and the sunlight, the better. Of course at this time the weeds are also getting themselves established and threatening to take control of the garden, and before we know it we’re planting, weeding, harvesting, 15-hour days, six days a week, maybe a day of rest, maybe not.

In the beginning of June, most of the planting is done and the major harvesting is about to begin. We start with the peas. In a good year we pick about 8 bushels of peas for the fourth of July. Some years we’ve already picked 40 bushels. This year I think we picked about four.

It’s not easy money picking peas. Doing a good job takes a long time. But it’s early money, which we sorely need to pay our bills; and, of course, the people love the peas. And they’re good for you, so I can’t think of a better reason to grow them.

Soon we’re getting into our money-making crops: squash, cucumbers, beans, cherry tomatoes. By the beginning of August the harvest is in full swing. This is when we start to get paid back for all the effort that we put in in spring and early summer, and this is when we can start feeding the people all the veggies that they crave.

It’s also time to start getting ready for winter. One of the things that I’ve learned about the market garden is that in order to have enough produce early on in the season, you end up rolling in stuff later on when everyone’s garden is coming in, and the real challenge is to figure out what to do with all that abundance. There’s nothing worse than having people come late September wanting pickling cucumbers and beans and corn to freeze and can, and you know that just a couple of weeks ago you had more than you knew what to do with. So we start encouraging people to stock up by giving them good deals on bulk produce.

Also in August we’re beginning our harvest of fall storage crops, garlic and onions, and what’s already a busy time of year all of a sudden becomes incredibly busy as you’re trying to bring in these crops. And somehow over the years we’ve learned how to get more efficient with this, and we’re no longer putting in these ridiculously long nights that it used to take to get everything done.

Fortunately for us at Peacemeal Farm, at the end of August, summer comes to an abrupt end, and before we know it we’re watching for frost, covering up the summer crops with Reemay to try to get a few more days out of them. Some people would consider this a disadvantage of our location, but I try to look at the positive side of it. Some crops, like carrots, really improve in quality when they’ve been frost-sweetened. Parsnips, Brussels sprouts, kale really aren’t even good to eat until they’ve seen a hard freeze; so I kind of look forward to those early frosts.

One thing I learned several years ago is that it doesn’t really matter what you’re bringing to market, if it’s bushels of tomatoes, melons, beans, or if it’s potatoes, onions, carrots. As long as you’re selling bushels of stuff, you can still make a living at the farmers’ market.

And so our biggest weekend in terms of sales is actually right down here at the Common Ground Fair, where we sell tons of produce to people to bring home for fall storage. But we continue to go to our markets after the Fair, all the way till Thanksgiving, when we have fresh vegetables from the field and the hoophouse, but we’re also selling large volumes of storage crops for the people to take home and store themselves.

Feeding the Community: More than a Niche

Some people dismiss the efforts of small farms like ours. I’ve heard conventional farmers say to me that what we do is a good niche, but we can’t feed the world this way.

I guess the first thing I say is that we’re not trying to feed the world. We’re just trying to feed our friends and neighbors and community here in Central Maine.

Other critics say that small-scale farming is inefficient and low-yielding, and that if we tried to feed the world this way, we would have to farm many more acres and still not be able to feed the world, while destroying lots of wildlife habitat.

I disagree with this. I was just trying to think of an example as we were getting ready for the Fair. We dug a bed of carrots for the Fair that we harvested 1,600 pounds of carrots off of. There’d have been about 20 of those beds in an acre, so it was about 1/20th of an acre, and that multiplies out to 30,000 pounds of carrots to an acre, which is at or above the California average for fresh-market carrot yields.

I went online to look at the fuel costs of delivering produce from California, and the best I could figure, based on a study out of Iowa, was that it takes a half a gallon of diesel fuel to truck a bushel of produce from California. I figure roundtrip, it takes us around a tenth of a gallon of fuel to make it to market and back and sell that bushel of carrots. So as far as I could tell, we could get as good or better a yield, and we can deliver it to market for about a quarter of the amount of fuel that they can – so I wonder who is, in fact, more inefficient.

I would like to read a poem by Wendell Berry who, in my early years, really inspired me to get into this. [Guzzi read “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front,” which is posted at www.context.org/ICLIB/IC30/Berry.htm.]