|

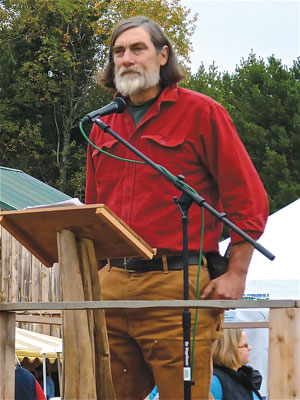

| Jim Gerritsen of Woodprairie Farm was the farmer-keynote speaker at the Common Ground Country Fair this year. He talked about his own development and experiences as a farmer, about the importance of his family and community, and gave tips for entering farmers. English photo. |

Observations from Thirty-five Years of Watching the Maine Organic Community Grow

By Jim Gerritsen

Jim and Megan Gerritsen have owned and operated Wood Prairie Farm in Bridgewater, in Aroostook County, Maine, for 35 years, and they are raising their four children there as well. Their farm, MOFGA-certified organic since 1982, focuses on producing organic early generation Maine Certified Seed Potatoes, seed crops, vegetables and grain. The Gerritsens sell their seed potatoes and other goods through their retail mail order catalog and Web business (www.woodprairie.com), and they sell wholesale to several national mail order seed houses.

Jim is president of the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (www.osgata.org) and has served for more than 20 years on MOFGA’s certification committee. In the 1980s he was a founding member of an Organic Crop Improvement Association chapter, served on the chapter board and chaired its certification committee. He has served as president of the Organic Seed Alliance (OSA www.seedalliance.org) and continues to serve on the OSA board. Jim is also on the board of directors of the Mail-order Gardening Association (www.mailordergardening.com), on the board of advisers of the New England Farmers Union (https://newenglandfarmersunion.org/), on the steering committee of the local USDA St. John-Aroostook RC & D (Resource Conservation and Development), is a founder and co-leader of Slow Food Aroostook and chairs the Bridgewater Democratic Town Committee.

Jim gave the keynote address at the Common Ground Country Fair on Sept. 26, 2010.

Good morning. I’m here to tell you today that organic is here, it’s growing, it’s strong, it’s permanent and it’s going to be the wave of the future. The perspective that I’m going to give you is that of a farmer in Aroostook County, Maine. We’ve been farming organically for 35 years; long before it was any advantage in the market place.

This Common Ground Fair has great significance to us. I met Wendell Berry at one of those first fairs back in the 1970s. We don’t get down here too often anymore. The last time we were down, Vandana Shiva was here and that was about five years ago. I think the Common Ground Fair is a wonderful symbol of the development of organic community here in Maine. The Fair always comes right during the middle of potato harvest in Aroostook County and getting away on a day that’s dry enough to dig is a hard proposition. So while we don’t often attend, the Fair is part of our annual calibration. We’re always very conscious of this weekend, very conscious of what weather is going on and its impact on fairgoers and vendors alike.

Now in many ways I seem to be the figurehead of our farm, Wood Prairie Farm. But really that’s not accurate. The reality is that we have a family farm and it’s very much a collaboration and a joint effort between all the members of our family: Megan, my wife, our sons Peter and Caleb, and our two daughters, Sarah and Amy. And we work hard. That’s the life of farming and it’s a great life, second to none. But when I’m away the others are back home quietly doing the work of the farm. Farming in this era is absolutely a family affair and everyone in our family is important and valued.

|

| Jim Gerritsen and family and friend, after the keynote. English photo. |

Farming in the Blood

My background is that I didn’t grow up on a farm. Both my parents were of the generation that grew up on farms and then they were part of that societal thought that there was a better life to be found off of the farm. My dad was born and raised on an apple farm in Yakima, Washington, in 1912. My mother was born and raised on a cattle and wheat ranch in South Dakota in 1923. I was raised in San Francisco and I was a real fish out of water. I never fit in to that urban upbringing. From the time I was about 5 years old – I’m 55 now so that would have been around 1960 – we’d go camping. And from that point on, camping and being outside was what I could relate to: outdoors where Nature is in charge. After graduating high school I went to Humboldt State and started out as a forestry major and soon determined I neither wanted to work for the U.S. government or for a paper company, which were the options for foresters. After working on some local farms, I quickly came to realize that farming was my calling. I think anybody with gumption that’s working for another farmer pretty quick develops a plan of having a farm of their own. So I continued to work, save money, and investigate different areas of the country to settle. I decided that Maine was the right place to head, specifically Northern Maine. The climate and geology of Northern Maine is well suited to farming. The soils are high quality. Coming from a California background 35 years ago, I didn’t want to get crowded out. I looked at the California experience and what makes California tick: the nice sunny weather; so I looked at the other end of the spectrum and I thought that with the cold winters, northern Maine would be a place that wouldn’t get overly crowded. And 35 years later it looks like I was right.

Aroostook County Farm

Back then in the mid ‘70s, I don’t think any of us realized it at the time, but Aroostook land was really a bargain. I bought my first 40 acres in 1976 for $150 an acre, which seems like an incredible deal. Until you consider my friend Jeff Kaley who four years before that bought a 120-acre farm in Bridgewater for $6000 – that would be $50 an acre. And it had the deeper Caribou loam and a woodlot that hadn’t been touched in 35 or 40 years. Well, before long the price of land started to rise, though I think Aroostook is still the bargain in the state of Maine. Aroostook County is a wonderful place; it has a lot in common with Alaska in that there’s kind of a pioneering spirit. We’re one of the counties in the United States where we continue to lose population with every census. But the people who are able to stick it out up there love it. And if you can figure out a way to make a living, it’s a wonderful place to live. If any of you are looking for land I’d recommend checking out Aroostook County, because I think there’s still affordability and it could be a future for you.

After buying the initial 40 acres, a few years later I bought the adjoining 40 acres, and then Megan came along – and we just this summer celebrated our 25th wedding anniversary. Shortly after that we bought the 20 adjacent acres and then 10 acres next door. And now we rent from our neighbor, another 5-1/2 acres. So we have about 115 acres; about half of that is woodlot. And we’ve cleared the trees off about 35 acres of the land that we farm. Nature is trying to reclaim abandoned farms. Aroostook was originally forest, and Nature would just as soon take that back and grow trees.

Aroostook Potato Harvest

The first fall I was in Aroostook, the fall of 1976, I worked for Eldon Bradbury of Bradbury Brothers in Bridgewater. At the time they were probably the largest potato farmers in town; they had about 300 acres planted. They had three potato harvesters and I worked on one. We worked six days a week from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. and took dinner from 11 a.m. till noon. Saturday we got done at 4:00 p.m. and got our paychecks. There were six people on our harvester and there were three harvesters, and they had seven trucks – each with a truck driver – and in the potato house they probably had three people working putting potatoes into bins. So on that one potato farm, there were almost 30 workers; and that was just one farm out of about 30 potato farms in our town. And every one of those workers, myself included, went to Clowater’s store in Bridgewater Saturday evening to buy groceries and get our checks cashed. I think $2.75 an hour was the hourly rate that fall. Well I added up in my head – because all the crews in town also went to Clowater’s to cash checks – and he had to have $100,000 in cash on hand. Now in Aroostook County there were between 1,000 to 1,500 potato farmers in those days. Multiply that by 20 people per crew and you can see how this was a big part of the culture of Aroostook county.

Now I’d like to take a few moments and read to you a short address I gave at the Slow Food Terra Madre meeting four years ago. The title of that address is “The Potato Culture of Aroostook County.”

Slow Food is an organization founded in Italy about 25 years ago, started up as an alternative to the cultural concept of fast food. To the Italians food is a big part of their culture, and they came up with this organization, which, in the intervening years, has gone international. Every other year for the past six years they have this meeting in Turin, Italy, called Terra Madre where they bring together 5,000 farmers and food producers from 150 countries around the world, and it’s a very powerful event. There’s going to be another Terra Madre meeting next month in Turin, and there are delegates from Maine going again. Megan and I went to the first one six years ago. And then two years later my then 16-year-old son, Peter, and I attended, and this was the meeting where I gave the following address.

The Potato Culture of Aroostook County, Maine, U.S.A.

Good morning. I’m Jim Gerritsen. We have a family farm and raise organic certified seed potatoes in the state of Maine in the United States. I’d like to thank the folks at Slow Food and our hosts here in Italy for the opportunity they have created in bringing together this wonderful group of farmers and producers.

Our Wood Prairie Farm is located in Aroostook County, the northernmost county in Maine. Maine’s biggest farm crops are potatoes followed by milk, eggs and blueberries. At 5 percent, Maine has the second highest ratio of organic farms to conventional farms in the United States.

The land that is now Aroostook County was uninhabited forest for thousands of years. Aroostook County’s history has been heavily influenced by two factors: potatoes and its isolation from populated southern New England by forested wilderness.

In the early 1800s, the first white settlers to Aroostook County started carving fields out of the forest and immediately began planting potatoes. What they found was that unlike the marginal soils covering most of New England, the geologically distinct, well-drained, fertile loam soils of Aroostook along with the cool northern climate were perfect for growing potatoes. Over the next 100 years, farmers made steady and massive efforts to clear the trees from hundreds of thousands of acres in order to grow potatoes.

The big revolution occurred when the railroad arrived in Aroostook County in the late 1800s. With good soil, climate, transportation, 40 inches of annual precipitation and relative proximity to East Coast population centers, Maine’s Potato Empire was created in Aroostook County. Through the early 1950s, the annual crop of almost a quarter million acres made Maine the leader in United States potato production.

In the last 50 years, Maine’s Potato Empire has seriously waned. Among the factors: * shifting consumer preferences away from fresh potatoes and home cooked meals to factory processed foods, such as frozen french fries and potato chips;

- successful standardizing marketing campaigns that convinced recent generations of American consumers that an “Idaho Russet” is the only potato worth eating;

- competition from producers in the American West who benefit from federally-subsidized irrigation and hydroelectric projects;

- the transformation of the traditional potato to a generic commodity with a capital intensive, highly mechanized, increasingly concentrated system of large scale, factory-like production;

- and finally, decade after decade of low farm gate prices.

While Aroostook County still produces more potatoes than any other county in the United States, our production is now just a quarter of its peak.

Despite this steady decline, Aroostook County still has a potato-based culture, much as it has had for the last 150 years. Going back many generations, everyone in Aroostook has worked in the fields picking potatoes. Many former farmers and non-farmers schedule vacation time so they can help family members harvest their potato crop. We are one of the last areas in the United States where schools are still closed for Harvest Break so that kids can help farmers get their crop in. Often the teenagers that we hire are taught potato picking technique by their parents and grandparents who, they themselves, learned when they were young pickers. In our potato culture there is universal belief that hard work and thrift are best learned at an early age by working in a potato field. This is an endangered tradition as increased potato mechanization reduces opportunities for both hand work and younger workers.

Now, a little about Wood Prairie Farm. We have been farming organically for 30 years. We own 110 acres. Like most Maine farms, half of our acreage is in forest. We farm 55 acres, including 48 acres in rotated crop production. We have a four-year rotation: year 1: potatoes; year 2: spring wheat or oats underplanted with clover and timothy grass. The clover sod from year 3 is plowed down in year 4, and the field is then planted first to plowdown buckwheat, then to plowdown rapeseed as a biofumigant. Year 5 is back to potatoes. Our rotation allows us 10 to 12 acres of potatoes a year. We also grow lesser amounts of other root crops, like carrots, beets, parsnips and onions. We plant in May, harvest by early October and ship from underground storage until June.

We sell seed potatoes certified as seed by the state of Maine to home and market gardeners across the United States through a mail order catalog and website. We also wholesale to mail order seed houses, who sell our organic seed potatoes in their catalogs.

In my remaining minutes I’d like to talk about the question of scale in agriculture. Within the Maine organic community, our 10 acres of potato production would be considered average. However it is very small compared to the 200- to 700-, even 2,500-acre potato crops of our non-organic neighbors. Yet the size of the thousands of farms back in Aroostook’s golden age were also small by comparison to today. Clearly, as average farm size increases, there is an even greater decrease in the number of farmers remaining. Fifty years ago our 4-mile-long stretch of road had 30 potato farms. Twenty years later our entire town was down to 30 potato farms. Today there are just six potato farmers left in town. One economist has projected that if current trends continue, Maine’s 60,000 acres of potatoes will one day be grown by just 20 farmers each growing 3,000 acres.

This upward trend in scale is similar across American agriculture. Two factors contributing to this trend are the short-sighted acceptance of genetically modified (GMO) crops by American farmers and the unrelenting rise of American corporate consolidation and domination, first within the U.S. economy and now within the national government.

Historically, it is worth noting that subsequent to the Populist Movement of the late 1800s, the American farm economist Carl Wilkin in the 1930s concluded, through his work developing the economic model known as Farm Parity, that restrictions upon the size of large farms was necessary in order to ensure proper functioning of the economy, economic justice for farmers and broad benefits to the whole of society. Thirty years ago American writer and farmer Wendell Berry published his landmark work The Unsettling of America, which expressed serious reservations to this then unquestioned trend within American agriculture of hyper growth, mechanization and consolidation.

The harvest we are now reaping from this modern scale is liquidated family farmers, crushed rural communities, an unstable food supply and an at-risk democracy.

Since its inception, the organic community has been a safe harbor for the American family farmer. However, corporate entry into organic production and marketing is now occurring at a rapid rate, and its influence is being felt nationwide. Go into an American chain grocery store today and you will likely find corporate organic vegetables, which have been shipped in from thousands of miles away, with no local products to be seen. This development is harmful to family-scale organic producers due to loss of market opportunity and downward price pressures.

Will organic family farmers succumb to the same forces of scale, consolidation and control that have led to the demise of other family operations? Three reasons for hope come to mind:

- first is the spirit embodied in the Slow Food dialog of honoring the producer and valuing food that is good, clean and fair;

- second is the developing concept of an “Organic Family Farmer” certification system that identifies organic family farmers in the marketplace, aiding co-producers seeking authentic goods and protecting real family farmers from corporate imitators;

- and third is the dawning on Americans that local is in fact better as reflected in the growth of CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture) and farmers’ markets.

Finally, on behalf of the organic family farm community in the United States, I would like to thank the world’s organic and farm communities for their courage, leadership and persistence in fighting the spread of GMOs. Your work provides monumental inspiration and assistance to those of us on the inside of the problem who are also working to stop biotech tyranny and their crimes against nature. Thank you.

__________

Terra Madre

During the first Terra Madre meeting – just to offer one little anecdote – with the help of some informal translators we were able to speak with and interview a subsistence potato farmer from the Bolivian Andes. Prior to coming to Italy this farmer had never been more than 4 miles away from the home he was born in. The deep commonality of northern potato farmer and Bolivian farmer from potato’s birthplace was very moving. Imagine going from that mountain village in Bolivia to Italy and being surrounded by 5,000 farmers. Mind you, farmers that are all hanging on by our fingertips in a world that is constantly telling us we need to move over, get out of the way and let corporations move in because they’re modern and more efficient and they know what the consumers want. Well, the reality in Bolivia, in Maine, in any country you pick, the success of the Slow Food movement is because the family farmers are holding on to the heirloom varieties that taste good and that produce well under difficult local climatic conditions. And that authentic food is the food that the world wants to eat. The food that the corporations are shoving down our throat, the use of our government to force American GMO grain into countries that don’t want it, that is not democracy, that is not what we’re after. The reality is that worldwide, family-scale agriculture is a vital force. Historically it has not received the attention of the media. But I think a lot of change has been brewing in the last five or 10 years and the media is now picking up on this, and farming is being viewed as one of the honorable professions. The family scale farmers are growing what the world’s people want. We have the real varieties of vegetables and fruits and grains and livestock that have a culture and a history attached to them. Contrast this with the generic commodities that industrial agriculture produces. Organic ag is central, and this Common Ground Fair is a reflection of this undercurrent that is destined to become the wave of the future.

The Simple Life

Back last summer we tried to take a few farmer-vacations, which means, if you don’t know, to take two or three days off. So we went down to Hancock Pond in North New Portland where Megan’s Aunt Margaret has a camp. She volunteers at the library and they have sales events to raise money in the fall, and on her shelf, unread, was a 25-year-old book called The Simple Life by David Shi. So I grabbed it and read. The idea of simplicity is something I’ve been fascinated by for most of my life. Despite the fact that this book was written in the mid-1980s, it was still fresh. The gist of this book – which I would highly recommend – is following the American history of simplicity as contrasted to complexity. Essentially the author equates material simplicity to spirituality: the more simple, the more spiritual; the more complex, the less spiritual. He goes back to colonial times and shows the very interesting thread of the survival of this concept of simplicity. For example during the American Revolution it became a patriotic fervor to be simple, because the luxury goods were imported from England, and if you were lusting for luxury goods you were supporting the enemy. Typically what would happen is that “visible” simplicity would fade and just about peter out and then maybe every 30 or 40 years there’d be a resurgence of simplicity, especially in times of economic stress like the 1890s, the 1930s, the 1970s. You’d see this popular return to simple values, for your family and your community on a broad scale.

I think the organic community has really never let simplicity go away. I know that within some of our subculture the idea of “spirituality” – when equated with institutionalized religion – is not a popular concept. But I think if you step back and look, that a lot of the values that we have within this organic community really are spiritually based values. I heard on National Public Radio in the last couple weeks a professor had completed a study on why rich people are so unhappy. Come to find out the rich often think happiness is gained by accumulating things; however, she found that in reality experiences are what makes you happy. Traveling, going to a camp in Maine, enjoying your family, enjoying nature, growing a garden, that’s where to find happiness. But instead the rich go out and buy material things. I think those of us in the organic community have already got that figured out: It’s part of our way of looking at life. The essence, the real value of life, comes from what we’re doing, the work of our lives, the people we’re interacting with, and it doesn’t come from the amassing of goods.

Our Organic Community

I think community is one of our important values and we have some good examples to learn from. Up our way in Aroostook we have two Amish communities and we have a Mennonite community right in Bridgewater. They’ve turned out to be really good neighbors. Sure we’ve got differences with the theology of the Mennonites and the Amish, but I think what’s so appealing about their culture is the effect of the subordination of the individual and the raising up of the common good. I think hunger for community is a major undercurrent within the organic experience. Cooperation and community, I think, is a major element that has made us strong and has been the underpinning for this transformation from a chemical intensive agriculture and now to the second stage where organic principles are being adopted and incorporated into conventional agriculture. They say there are three stages of historical change: first, is a total rejection of the new idea, second is the incorporation of the new idea into the status quo, and the third stage is when they say: “but this is the way we’ve always done it!”

I think the true definition of community is the extension of values that we lay upon our family, to our neighbors and the people around us. And I believe this organic community in Maine is extraordinary and a leader of the organic community throughout the United States. I increasingly hear the term “Organic Industry,” and for those of us who have been in it a long time, we still consider this instead to essentially be an organic community. Now the money-folks that come in because there’s money to be made here – is their soil going to be good after a 36-month withdrawal from chemicals? Will their crops be as good as from land that has been carefully managed organically for 30 or 40 years? No, I don’t think so either. But the room is big and there are many doors and we need to let them all in to bring about the change. I think the real important thing in organic is the organic community. Our Amish and Mennonite friends have done a good job at seeing value in working towards something greater than yourself: You contribute to the raising of the community good as contrasted to the selfish “get the hell out of my way” attitude. It’s more Dalai Lama than Dick Cheney. This Common Ground Fair is a celebration of that sense of community.

Organic is Superior

Here’s a proposition I’m going to put out there: I believe that organic farming is the superior system in terms of deliverables. The food is higher quality; if it’s grown right it is nutrient dense and good tasting. From a resource standpoint we’re successful at nutrient cycling; we avoid putting chemicals into the environment. And from a societal perspective we strengthen democracy and justice by having a strong network of family farmers producing organic food for people in our region.

When I think of nutrient density, I’m reminded of a friend of mine, he’s one of the pioneers of organic potatoes in Aroostook County: his name is Chris Holmes and he’s up in Presque Isle. Now back 30 years ago, when the organic market had really not yet developed, and Chris had been experimenting growing organic potatoes and had a crop harvested but with no home for them. So he ended up taking them to the french fry factory in Presque Isle. And when his truck got to the plant they’d stop and weigh the load and then they would take a specific gravity reading. Chris was quite a character and he wouldn’t say a word about the potatoes being organic, and the fellow did a sampling of his Kennebecs and shook his head and finally said, “I guess we’re going to have to test your load later, because my meter seems to be broken. The gravity registers off the chart.” Now a wet potato, a low gravity potato, has more water and less solids. A high gravity potato, a dry mealy potato, would be high solids and less moisture. There are other ways of lowering the gravity content: If you have excessive irrigation or excessive fertility, you can create a watery potato. I was witness to a conversation of an Aroostook County potato grower, he was a process grower for McCain’s and he was bragging that he’d put 1,000 pounds of potatoes into storage in the fall, and he ran so much humidity in his storage that his potatoes would pick up moisture and he would be able to ship out 1,050 pounds of potatoes, and he was pretty proud he was getting paid for that extra 50 pounds of potatoes.

I see we have good individuals at the university. And Wayne Honeycutt who is the head of the USDA ARS lab at Orono; he and his scientists are doing some really good research there. They don’t call it organic because that word would bring some thunder down upon them, but it’s good science that benefits all farmers. When researchers go and do their yield trials, they compare pounds to pounds. Well, if you have a truckload of conventional potatoes and a truckload of dense organic potatoes, you’re getting a lot more nutrition and value out of those organic potatoes. So it’s not fair to simply compare it hundredweight to raw hundredweight. You’ve got to account for quality.

Do Your Homework

So I’d say one of my beliefs is that all of us need to do our homework: We’ve got to educate ourselves. The media has devolved to the 15-second sound bite. If you can’t explain it in 15 seconds, it’s going to go over the heads of your audience. The reality is we have to be doing our own homework. Fortunately we have some really talented people out there that can conceptualize and explain these things we need to gain an understanding of.

In order to make sure our families have access to good food, we have to do our homework. Wendell Berry and Michael Pollan have been grappling with these issues. Lisa Hamilton is a wonderful young writer. How many of you have read her book Deeply Rooted? Lisa goes into depth relating the struggles and strengths in this modern age of three different family farmers: one a dairy farmer in Texas, another a New Mexico beef farmer, and third, the organic seed growing Podoll family in North Dakota. We’re kind of partial to the story of the Podolls, because they grow seed and they are our friends. The story is David Podoll in the 1970s was a young conventional farmer who went to investigate organic farming and expose its errors. Come to find out he concluded organic farming was the superior system and he switched. So back then in North Dakota you didn’t admit to your neighbors that you were an organic farmer. Later on, David’s younger brother Dan was in college in North Dakota along with Dan’s future wife, Theresa, who grew up on a conventional potato farm in the Red River Valley. Dan and Theresa had been dating for six months before Dan finally admitted to Theresa that yes, he and his family farmed organically. Now they’re among the best organic seed growers in the country.

The issue of GMOs is a complicated issue but if we close our eyes to it and leave it to the government, we see what a mess that has become, and they end up making the wrong decisions for us. So another book you ought to read is Uncertain Peril by Clair Hope Cummings. Clair served with me on the Organic Seed Alliance board of directors, and her book is a great explanation of the problem with GMOs in food, and I hope everyone will read it. Fred Kirschenmann, another friend on the OSA board, has a new book, Cultivating An Ecological Consciousness. Fred is a real gem, he comes from the background of a large-scale organic farm in North Dakota, and he’s very eloquent in his writings. And, finally, last but not least is The Maine Organic Farmer and Gardener newspaper that Jean English is the editor of. Of all the different publications we receive, I’m amazed at the quality of The MOF&G, and I think Jean and her crew do a great job. That’s a real testimony to what’s going on in Maine.

Farming Homework

Now if you want to get into farming, we also have some good farmer-writer-teachers here in New England. One is Eliot Coleman. He has several books and the first one I would read would be The New Organic Grower. There’s a new book that came out last year by Richard Wiswall in Vermont called The Organic Famer’s Business Handbook. Richard is an organic market grower in Vermont, and he has a good business mind. If you’re going to farm and make a living out of it, you have to run your farm as a business.

And here’s something else we’ve learned: You might just as well focus on your soil and micronutrients now, because in the end that’s what makes you a better farmer. You should be aware the Heart of Maine RC&D, every February, has a two- or three-day soils school in Bangor. They’ve brought in Arden Andersen, Neil Kinsey, Dan Skow and Gary Zimmer, cutting edge teachers on soil and good farming. MOFGA also has the exceptional Farmer to Farmer Conference held each fall in Northport, the first Friday, Saturday and Sunday in November. It’s a very good format for allowing farmers to share their knowledge along with Cooperative Extension folks. One of the things that’s particularly pleasing to me is to see how many young people are now attending this conference. The most optimistic development in agriculture is seeing young folks get involved.

Support Your Allies

All of us live busy lives, farmers and non-farmers alike. What I want to convey is this idea that we can multiply our individual effect by supporting our allies. There are individuals and groups out there that are working on your behalf and they deserve your support. MOFGA is the first group that comes to mind, and this fair is a reflection of the year-round good they do. MOFGA started 39 years ago when some idealists decided we needed to grab hold of the food system in Maine and make change. And if you’re a farmer that’s farming organically in Maine, you need to get certified by MOFGA. When Russell Libby goes to the legislature and gives testimony, it’s one thing when he’s there representing 400 Maine certified organic farmers. But there are likely an additional 300 or 400 farmers that could and should be certified. Russell would carry a lot more weight with the legislature if he spoke on behalf of 800 certified organic farmers.

There are several grassroots groups in the state of Maine that have merit. Among them you should consider joining, Food for Maine’s Future and Cultivating Community. MOFGA does a wonderful job working on issues locally here in Maine. But a lot of the decisions that impact us here in Maine are taking place outside of Maine, and it’s very important that we have advocacy for a progressive agriculture on the national level. And a wonderful development in the last few years here in New England is we a have a charter chapter of the 108-year-old National Farmers Union called the New England Farmers Union. I’m on the NEFU board of advisors, and I would encourage you to come and learn about NEFU and join up. When I’m done speaking here I’ll be over at the NEFU booth.

Social Tithing

Here’s an idea that goes back to a concept the Mennonites and the Amish practice and it’s the biblical concept of tithing: They give 10 percent of your earnings to the church. I think a good idea for us would be to adopt a practice of “social tithing”: Commit 10 percent of your earnings and your energy towards a good greater than yourself. Say if you earn $20,000 a year, 10 percent is $2000. Use that to buy a CSA membership, become a member of MOFGA, become a member of NEFU, send a campaign contribution to Mike Michaud or Chellie Pingree who are doing a good job representing the state of Maine in a very hostile Congress. Join up with groups that are working to create opportunities so that young people who have the desire to farm, but not the resources, can connect with farms passing down from one generation to the next. At this Fair there are 1,000 or 1,500 volunteers who are donating their time to make this Fair a success. That kind of giving makes our community stronger, and it’s innate to us in the organic community. Giving is where our real strength is.

Now Monsanto has gained their influence from apathy, from behind the scenes dealing, and revolving doors, and from giving research funding to land grant universities. The fact is if we can use the social tithing concept to fight the apathy, to get out this November and vote for progressive candidates. Over the eight years of the Bush administration, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Anti-Trust division was asleep at the wheel. They did nothing as Monsanto bought a large amount of the corn genetics in the Midwest: family companies that had been in existence 40, 80 years. Monsanto bought the genetics and now they are stacking on GMO traits. And conventional farmers find if they need to buy seed there are mostly just GMO seeds available. The same with soy and cotton. So, Monsanto now controls most of these seeds. That kind of monopoly does not work in a democracy. Enter the Obama administration. Now there are joint hearings going on with the US DOJ and the USDA on concentration in agriculture, and Monsanto is in the hot seat.

Obama and the new administration are doing the best they can with the bad hand they’ve been dealt. There remain a lot of things that need to be done, but due to the economic meltdown from the Bush years it’s all they can do to prevent us from slipping into a depression. We will be fulfilling our opposition’s greatest dreams if by apathy we stay away from the voting booths in November. We need to support our allies, the ones that are in government, in university – many have to still keep low profiles because they can’t openly support organic. They need your support, and unless we fight the apathy, there may be a real disaster this November.

Organic Farming in a Dysfunctional Economy

Our family made the decision years ago that if we were to succeed at farming we had to mechanize at an appropriate scale, because potatoes are heavy. Equipment costs enough but the cost of repair parts is absolutely stunning. There is no relation to the cost of production. I imagine every middleman is putting his 300 to 400 percent markup on the parts. We’re replacing a worn out king pin on a forklift. Parts worth $50 will cost us $650 to get us going again, and the parts fit into the palm of my hand. There’s more than one way to transfer wealth away from the middle class! That reminds me of a news story that was on NPR the other day, and it talked of a pill in use since the 1950s. If you went to Brazil today and bought one pill it costs 7 cents, but in the U.S. it costs $160. Farming in a dysfunctional, greed-based economy means to make a living farming is a challenge.

Farming Nuts and Bolts

If you are a new farmer I think the best thing to do is to grow vegetables. Vegetables return a high gross income, and startup costs are modest. Once you become competent you can sign up CSA subscribers and sell to them every year. If you are an eater and not a grower you can join up as a CSA member: That’s the number one way you can help young people succeed at farming in Maine.

Start your farming small, avoid debt, and put off getting into debt until you’re stable and know what you’re doing. Focus on vegetables. I see many folks go with livestock and few that make much money at it. In the state of Maine we’re small farmers, we’ve got to make our living from quality and working the margin, because we don’t have the scale to make it on the volume. The guys working 2,500 acres that are buying $500,000 potato harvesters, they’re working on volume. But those of us family scale have to work on the margin and we need to sell face-to-face to the consumer.

You need to get equipment to be efficient. If you start with a 1/10th of an acre garden and move up to 2 acres with the same technique, you’re going to burn out. Invest $100 to get a year’s subscription to Uncle Henry’s Swap Buy Sell Guide. Buy at least one piece of good equipment a year, with the criteria that it makes you more efficient. To get nuts and bolts details, come to Farmer to Farmer Conferences, and farmers will share knowledge gained over the last 40 years.

Another thing: Buy a forklift. You can see them in Uncle Henry’s for $2000. Organic is heavy, we use rock powders; they come in 1-ton tote bags. You have to be able to get it off the truck. Most organic growers should have a forklift, or at the very least a bucket tractor with forks.

The final thing I’m going to say is, it took Megan and me many years to develop our niche. We have a mail-order catalog, which we’ve been doing for 20 years. We’ve been farming for 35, so for about 15 years we tried growing strawberries, and dry beans and vegetables and beef and sheep and a CSA. Don’t get frustrated. Your niche is out there; you just have to be open to finding it. Grow what you love. Organic farming is the best life there is, but it’s not the easy life. If you don’t like work, go into something else. But farming’s great, MOFGA’s great, and this Common Ground Fair is a wonderful demonstration of organic coming of age. Thank you!

Jim & Megan Gerritsen, Wood Prairie Farm, 49 Kinney Road, Bridgewater, Maine 04735; (800) 829-9765; www.woodprairie.com