|

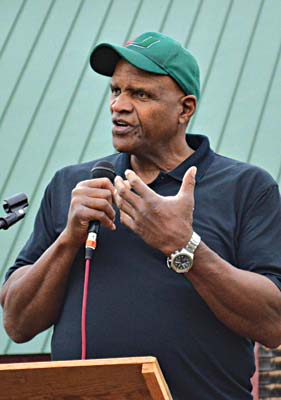

| Will Allen described Growing Power Inc. during his keynote at the Common Ground Country Fair and said the program is growing farmers because, in part, “it costs 10 times more to send somebody to jail than to help fix their life.” English photo |

|

| Will Allen lunching and talking veggies with MOFGA member and Exhibition Hall co-coordinator Amy LeBlanc. English photo |

Growing Power and the Good Food Revolution

Friday, September 23, 2016 – Common Ground Country Fair, Unity, Maine

Will Allen, a keynote speaker at MOFGA’s 2016 Common Ground Country Fair (view the speech on YouTube), is an urban farmer who is transforming the planning, cultivation, production and delivery of healthy food to urban and rural populations. The son of a southern sharecropper, he was a professional basketball player and then worked in corporate sales and marketing at Procter & Gamble. In 1993 Allen purchased the last remaining registered farm in Milwaukee, where he founded and now functions as farmer and CEO of the world-preeminent urban farm and nonprofit organization Growing Power Inc. He is a national and international leader in urban and rural agriculture and food policy.

Growing Power shows how local food systems can help troubled youth, dismantle racism, create jobs, bring urban and rural communities closer together and improve public health. The organization helps develop community food systems across the country.

Getting Started

Growing Power started when Allen was driving down Silver Spring Drive in Milwaukee. “I was working for Procter & Gamble in sales and sales technology, and I saw this old greenhouse operation. Something made me stop. It had a for-sale sign. I called the number, and it was owned by the city of Milwaukee.”

Allen contacted the city council’s real estate committee, which included a former priest – “a farm boy from Sheboygan, Wisconsin.” He liked Allen’s proposal for developing urban agriculture because, said the councilor, “I have enough churches in my district, and what he’s about to do is religion in itself” – working with young people, teaching them how to grow food sustainably.

During his keynote, Allen noted the “serious issues with food, especially in our cities, where most people live.

“We’re not doing a very good job making sure people are eating good food,” he said. “That’s what we focus on at Growing Power – to try to take the leadership to make sure that people have access to good food.” One way Growing Power does this is by growing farmers, who then gain meaningful employment in areas lacking jobs.

“In Milwaukee,” said Allen, “there’s a 20-year discrepancy in life expectancy when you drive from one community to another. We have the highest infant mortality rate in the nation, which is related to [lack of] prenatal care and the food that people eat. We have one zip code that’s the highest zip code in the nation for incarceration of African-American males.”

With federal funding received by the city of Milwaukee, Growing Power trained 150 people to build hoophouses, make soil and compost, and to farm.

“This was a workforce development project,” said Allen, “so my idea was to pay $12 per hour for these individuals. We interviewed over 300 – most with felony records, many of whom had not worked for over 10 years.”

Participants who made it through a year would then have a fulltime job. Of the 150 trained, about 50 were hired as permanent employees.

Next, as Growing Power planned to hire more than 5,000 people over 10 years, the organization learned that “you have to treat the whole body … It’s not just giving them a job. Many, even though they pass a drug test, were still using alcohol or drugs. Many were living in multiple places, so tracking them for our evaluation was difficult. We learned that you have to have a social worker or connect with a social services agency; you have to have a psychologist. They’re not ready to work an 8-hour job. You have to do it in stages.” So that next proposal requested funding to treat the whole person.

“Otherwise,” said Allen, “they’ll go right back to what they were doing on the street, or incarceration.”

Growing Crops and Relationships

Allen started by engaging kids and families.

“If you set up in any neighborhood in a city in America, kids are going to come because they have nothing to do,” he said. “I started to engage those kids, got to know their parents, and we started a youth corps of kids starting at 8 years old.”

The previous owner of the greenhouse had had a bad relationship with the community, so the greenhouse glass was full of holes made when kids threw rocks. “That stopped when we engaged the kids and got to know their families.”

Then Allen started working with kids who had been sent to youth prison – many because they had had poor representation and thus spent four or five years incarcerated.

“I worked with them in a therapy program of growing food, because I think we all know that when we touch the soil, it’s a very spiritual thing. To be able to work in the soil really heals people. That’s what happened with these young people. They really enjoyed working in the soil, and seeing something coming from a seed to a finished product was unbelievable to them. They never knew where their food came from. They thought it came from the grocery store. Sowing, harvesting, cleaning, learning how to cook with it – that’s been the basis of our work all of these years.”

Adults wanted to learn, too, so Growing Power started and continues training programs in both urban and rural farming, some on pockets of land within half an hour of Milwaukee.

Growing in a city is much different from rural farming, said Allen, because about 80 percent of the land is asphalt or concrete. He started by producing thousands of yards of compost.

Growing Power looks for larger spaces and builds 20- x 96-foot hoophouses using a jig to bend 17-gauge pipe (the top rail of a cyclone fence). The farmers put wood chips on top of the asphalt and then build beds that are 36 inches wide and 24 inches high, with 18-inch pathways. Four beds fit in each hoophouse and are filled with “some of the best compost that hasn’t been run through a screener.

“Many groups try to grow with topsoil,” said Allen. “As soon as it rains, all of the fertility flushes out … That doesn’t happen with our system.”

They now grow year-round in about 150 double-poly hoophouses – even when temperatures hit -10 F, thanks to 10-foot-diameter, 6-foot-tall composting mixes of wood chips and donated brewery waste in the four corners of each house. Each pile is capped with about 2 feet of wood chips and reaches a maximum temperature of about 150 F. Also, the exterior of each house is banked with wood chips to exclude cold air.

Nine-gauge wire every 3 feet supports plastic row covers over the beds when temperatures drop to 25 F or below. The row covers are opened whenever possible to allow for air flow.

“That’s how we grow about 40 different winter-hardy greens, many of which you’ll find in the Johnny’s catalog, where we order much of our seed,” said Allen.

Cost-efficient Aquaponics

Growing Power has been practicing aquaponics – growing fish and plants in the same system – for about 20 years. “We have the largest aquaponics system in the Midwest growing lake perch, a favorite for fish fries in Milwaukee and around the Midwest,” said Allen. The system costs a fraction of off-the-shelf setups. “A 10,000-gallon system can be constructed for under $20,000 but probably costs half a million dollars if you’re using a mechanical system.”

They grow over 100,000 fish per year – “a drop in the bucket from where we need to be,” said Allen.

“Commercially,” he added, “you cannot fish for lake perch in the Great Lakes anymore because the numbers are so small and the fish are contaminated with mercury. The only way to get a clean or natural fish that you can eat every day of the week is to grow it inside.”

Growing Power digs down 7 feet and builds its fish tanks into the earth, which helps stabilize the water temperature. Perch thrive at 68 F – the temperature this system maintains for 10 months.

“Aquaponics is the fastest growing piece of agriculture in America today,” said Allen. “You’re able to get two crops: the fish that take about 13 months – three months as fingerlings at a hatchery and then 10 months in a grow-out system. You can harvest greens and tomatoes and other crops on vertical beds because it’s important to be able to use vertical space. This is high-value space. We’re growing on seven levels in some of our houses.

“We’re growing at least $5 per square foot, which equates to over $200,000 per acre. When growing things like microgreens, sunflower sprouts, pea shoots and spicy sprouts, you’re talking $50 per square foot per annual year. That’s what the future will look like and what people are trying to do inside cities … because it makes no sense that 99 percent of the food that comes into Milwaukee travels from over 1,500 miles away.”

Growing Power, with its annual operating budget of about $5 million, has trained over 1,000 people in the last 10 years in aquaponics. “You leave training at Growing Power able to build a system,” said Allen.

The only way we can end poverty in the world, he continued, is to do it on a local level, to make sure people have access to good food. Growing Power uses Sysco and six other wholesalers to move its products to local markets.

Message to Washington: More Farmers Needed

Allen said we have to let our politicians know, for the next farm bill, that we need money for farmer training programs such as MOFGA’s and Growing Power’s and others’ to replace our aging farmer population. “We have to grow some farmers,” said Allen, adding, “Washington needs an office that represents small farmers.

“To be a sustainable farmer is the hardest thing you can do, but it’s the most rewarding thing to be able to feed people good food, to be able to celebrate things with good food. It brings people together, changes the way we look at each other, the way we talk to each other. Everybody should have that opportunity to be able to sit down and eat some good food.”

Funding farmer-training programs also makes sense considering that “it costs 10 times more to send somebody to jail than to help fix their life,” Allen noted.

– Jean English