|

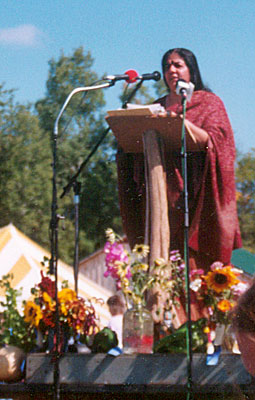

| Vandana Shiva told fairgoers that she hoped “this country … will be able to go beyond the contemporary slogan of ‘God Bless America’ to ‘God Bless the Earth.'” English photo. |

Keynote Speech by Dr. Vandana Shiva at MOFGA’s Common Ground Country Fair September 23, 2001

Introduction by Heather Spalding, Fair Director

This is a very special year in the history of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association and the Common Ground Country Fair. It marks the 30th year point for MOFGA and the Fair’s 25th celebration of sustainable rural living in our wonderful bioregion. So happy birthday to all of us!

We’re deeply honored to have Dr. Vandana Shiva with us today to share her experiences as an international leader in many environmental and social movements, particularly in her efforts to promote organic farming. Dr. Shiva came to Unity all the way from Doon Valley, India, and she arrived just yesterday afternoon. Unfortunately she has to return to India, and she’s leaving shortly after her address today. In the midst of all the international uncertainty and terror, we especially appreciate her courage and resolve to travel half way around the world to join the Fair and share her experiences with us.

A special thanks too to Vandana’s dear friend Jean Grossholtz from Mt. Holyoke College, who chauffeured Vandana up to the Fair. And also to the public media that is taping this presentation: WERU community radio; Maine Public Broadcasting; and Bath Independent Television.

Sixteen years ago, Dr. Shiva founded the Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology based in New Delhi. This foundation and Dr. Shiva are among the world’s leading voices on issues ranging from seed saving to globalization. Vandana, who is trained as a physicist, is renowned as an international expert on many issues and has had a great influence on the development policies of national heads of state. Still, even though she’s traveling all over the globe and meeting with world leaders, her passion really lies with the organic farming movement in India that, like ours, is a powerful counterpoint to large-scale agribusiness.

Dr. Shiva has a farm in Doon Valley in the foothills of the Himalayas, where she works with women to advance their interest in organic farming, and she’s deeply committed to grassroots organizing. The work that Vandana and her colleagues carry out in India parallels the work that MOFGA and the Fair carry out on a daily basis. We are reaching out to people, we are helping farmers in their transition from conventional agriculture to organic farming, and we’re creating markets for organic farmers and providing information to consumers who want to know where to get locally produced and healthy organic foods. We had a chance to visit last night and talk about the importance of exchanging ideas, information and experiences. Some of you may know that MOFGA has developed a sistering relationship with some of the farming communities in El Salvador. This [exchange with Dr. Shiva and her Foundation] is just another opportunity to learn from and build bridges with farmers in another huge section of the world. Vandana’s enthusiasm for what she’s seen at Common Ground so far really underscores the possibilities for these partnerships.

Please join me in a very warm and heartfelt welcome for Dr. Vandana Shiva.

|

| Fair Director Heather Spalding and keynote speaker Vandana Shiva at Common Ground in Unity. English photo. |

Dr. Vandana Shiva

For me this is truly a journey for peace. I undertook it in spite of everyone worrying – about taking a flight, coming to this country at this point of history. But that’s precisely why I got onto the flight, because if you give up hope, what chance is there for peace?

But it’s also my tribute to all of you who built this amazing movement here out of a peace movement. After all, those of you who came to Maine, built the organic movement, did it as an extension of fighting in a peaceful way against a war mentality. And my own work in agriculture and food, to build peaceful systems, organic systems, nonviolent systems, is related to my own rejection of violent methods, whether it is for politics, for technology or for the way we grow our food.

We have had our own share of terrorism in India, probably a bigger share than what New York experienced on September the 11th. And for me, the links between the way we do farming and how we create violent societies and violent minds was on June the 4th of 1984. That was our September 11th. That was the day the Golden Temple was taken over, after about four years of terrorist activity in Punjab that killed more than 50,000 innocent people. Every time I wanted to go to Punjab in that period, [I] couldn’t take a train – it had been blown up; a bus had been blown up.

But Punjab is the region with the highest per capita income in any region of India. It’s the region where the Green Revolution, the name of industrial agriculture, was introduced in the Third World. It is what is cited in all industrial agriculture propaganda as the success of agricultural technology. And yet after 20 years of introduction of the Green Revolution in 1965, 1966, with all the might of the United States, where it was brought in as conditionalities of the World Bank, we were told we could not be organic farmers, we had to adopt chemical agriculture, otherwise there would be no loans, no credit, no food.

When 20 years later, after the entire financial system created subsidies to introduce expensive agriculture to poor peasants, and in a poor country, we had young people taking to guns. This was an agriculture that was called the Green Revolution in contrast to the Red Revolution. China had had the Red Revolution; India was going to be different, because peace would be brought through prosperity, and prosperity would be brought through commercial, industrial agriculture. Twenty years later, that dream lay in shambles. What it brought was violence, it brought civil war. The most fertile soils of India’s Punjabi Plain, that had never had declines in years over centuries, in 20 years started to have yield collapses, half the soils were desertified, waterlogged.

And just as the violence now of September 11th is being associated in a very disconnected way with a particular religion, a particular region, a violence at that point that came from three clear factors: One: the problem of disenfranchised people. What the Punjab people were saying was,

“How can we survive if the prices of our food are not fixed by us? How can we survive if the water from our rivers is not released by us, but by Delhi and its politics with respect to different states? How on earth can we be free if we cannot decide what we’ll grow? Delhi will decide that we will grow only wheat and rice; decide the package with which they’ll grow; the irrigation that it will have; the prices at which commodities will be sold.”

They were rejecting what they defined in very clear terms a context of enslaved agriculture, an agriculture that had left them poorer, that had destroyed their soils, that had destroyed their children, that had not just committed violence to the earth, but committed violence to women and children like we have not known in India.

We have a strange phenomen[on] that started along with the Green Revolution, and in my book Staying Alive, I try to make links with this phenomen[on] of female feticide, of killing the female fetus with the high technologies of medicine that went hand-in-hand with the high tech of agriculture, because suddenly agriculture in India was no more the entire community working with the land in peaceful ways but was men reduced to pesticide sprayers and tractor drivers and the women with no role in agriculture production. They had been turned into the dispensable sex, and having been made redundant, they were then being killed in the womb.

My sister’s a doctor and very active in the movement against female feticide, and the counts that they have generated as the health community in India is 240,000 women aren’t getting born any more because of the kind of agriculture we brought to our rural areas. To me, that’s terrorism against future generations, particularly against the girl child.

Well, the frustrations of Punjab and the community of Punjab, which happens to be a Sikh community, because that’s what the peasants there are – they all wear turbans, they all have beards – to deal with it in a way that did not bring a democratic response, our prime minister then – and I’m giving the details because the parallels to what’s happening now in this country are so similar – Indira Gandhi decided that she would not respond to give power back to the farmers, give power back to the regions and the states; she would hold on to power and create an extremist fringe to marginalize the democratic forces of the state. So she created a bin Laden of that period for Punjab, a person extremists called Bhindranwala. She financed him, she gave him guns, she encouraged him to fight by other means, exactly like bin Laden was encouraged, and before we knew it, Bhindranwala had become bigger than the other forces, just like the Taliban became bigger than the democratic forces in Afghanistan. And when they started to literally create violence of unprecedented kinds and took over the Golden Temple, they were hiding behind them the democratic demand of farmers for a decentralized agriculture that allowed peasants to survive. The farmers had declared on 4th of June a total blockade for the supply of grain to Delhi. And that’s the day the Golden Temple was attacked. It was an attack that looked like it was an attack on extremists but was an attack against the farmers’ movement. And I have documented this in detail in my book called The Violence of the Green Revolution.

Well, after she attacked the Golden Temple, she didn’t just attack Bhindranwala, she didn’t just kill Bhindranwala, she assaulted the most sacred shrine of a major religion. The entire religion had mobilized in ways that could not be anticipated, and it was two Sikh security guards of Indira Gandhi who assassinated her in her own home, because she used violence to deal with power, and it came back to her. And then we had the worst massacre of Sikhs. Just as we are having, unfortunately, a backlash against all of our national Arab communities, and just because bin Laden’s picture is shown daily on the world media, there is an assumption that everyone with a beard and a turban is a terrorist, and I know two Sikhs have been killed in this country in the backlash, but I also know my community here is absolutely scared. They came here very different, in a very different migration pattern. They came here as professionals. They came here as professors, as doctors, as engineers, and today, in the mindlessness and madness of xenophobia, no matter how privileged they are, they realize they are not safe.

Violent systems of agriculture and economies are what create the basic groundswell for extremist action, particularly if the democratic ways of people to express their anger, their discontent, their wanting alternative ways, are squashed. Every time extremism occurs, every time terrorism occurs, it’s a symptom of the death of democracy, and the only way it can be responded to is through democracy and peace.

Now, when you think of the fact that our agriculture today, the dominant agriculture today, is an agriculture of war; it’s an agriculture that started to use war chemicals after the war had ended. All the pesticides, all the fertilizers were really war chemicals. And it came home to us in India when the Bhopal disaster – another example of terrorism – killed 3,000 sleeping people from the leak of a Union Carbide pesticide plant in the heart of India. Bhopal literally means “the good earth.” And that good earth was totally violated in dramatic form the way it is violated daily on our farms across the world.

But in the last 10 years as I’ve been working more and more on genetic engineering, I think of the fact that the very beginning of that technology that is to replace the Green Revolution and its violence begins with gene guns. They begin with a war against all life. And what are the resistances that they are building into plants? Resistances to what we would really imagine is not about a wholesome relationship with the earth, but use of chemicals with trade names like Roundup and Avenge and Prowl and Specter and Squadron. You could take everything in the military deployment and find the name in our agriculture, on our farms. We have declared war against the earth, and each time we talk about the disaster of September 11th, you know I just shut my eyes and say, “What happens to the plants in those fields each time Roundup is sprayed? Isn’t that a terrorist action against all beings?”

While we have been having debates on genetic engineering, on the corporate control of agriculture, there are two phrases that stick in my mind about the mindset about the corporate giants who want to control the world because they are so scared of its freedom and diversity: I believe violence comes out of fear; I believe peace comes out of confidence. And when we were basically resisting Cargill from coming into India during the early days of globalization, and they were bringing in new hybrid seeds, and our farmers had had a major action against the Cargill seed farm, the Cargill chief said that Indians are so stupid, they don’t know we have smart technologies that prevent bees from usurping the pollen!

Bees have rights to pollen before we do!

And then on Roundup Resistant plants, this really takes the cake. You know for us, weeds are the basis of our survival, because weeds are what nature gives us in her generosity. They’re the medicinal plants, the pomela that cures jaundice, the greens that we can use for fodder for feeding our cattle. We have many landless in India, lots of landless women, but they all make a living by having access to the free greens in the free commons. And that’s the fodder that goes to feed their one goat, their one cow, that then feeds their children. But all these weeds, this amazing diversity – and our studies show 250, 350 species on farms which have the generosity to be at peace between species – according to Monsanto, all these weeds are stealing the sunshine! And therefore you have legitimate right; they are terrorist, so you can afford to be terrorist against them. Deploy the worst of military weapons on that diversity on our farms.

I was just reading before coming here how in Africa it’s bringing back weeds that is becoming the best way of controlling pests as well as noxious weeds, because it’s the only way we can. And in fact, if you really want to see how the cycle of violence increases at every step, we just have to think of what pesticides do to pests. They don’t wipe them out, they just make them resistant. And that’s a message I’d like Washington to get.

We’ve had our violence of the ’60s, the ’70s, the ’80s, but the violence of the ’90s goes beyond any limits, and there are two particular tragedies taking place in India right now, tragedies comparable to the attack, the totally unjustified attack, on the World Trade Center. But these tragedies are also totally unjustified. The globalization of our agriculture has meant the companies can come and sell expensive seeds, expensive chemicals, and give the credit for it. They are literally the government, the money lender, the marketing agent, all in one. And within a decade of that kind of ‘liberalization,’ as it is called (I don’t see it as liberalization), our farmers have become so indebted, they can’t get out of the debt.

And they’re consuming the same pesticides that got them into debt, to kill themselves. And two districts particularly, one in Andra Pradesh, one in Punjab, both districts with the highest use of pesticides, the most rapid increase in use of hybrid cotton seeds, 20,000 farmers and more have committed suicide. Farmers are selling kidneys to be able to continue to do agriculture, and they can’t, because once you’ve sold your kidney, you can’t work on your farm. They’re selling their children, they’re selling their wives.

Of course there is more growth, and of course Monsanto has bigger market sales, but those market sales are coming out of squeezing life out of our rural communities and our rural ecosystems. And all this is also done in the name of bringing cheaper food to people. Remember the propaganda of GATT? It will bring cheap food to people, it will remove hunger from the world, genetic engineering will do that, the new technologies will do that? For the first time since the British were told to go by the Indian people, we are having a return of famine. Not because we don’t have the food; we have the food. But the World Bank and the World Trade Organization have joined forces to ensure that Indian food doesn’t reach Indian people. We have at this point 60 million tons of food grain rotting in our go-downs [warehouses]. The World Bank is encouraging the government to dump it into the ocean or export it at half the price. But the World Bank is preventing the government from giving the food subsidies that would allow this food to reach the poor.

Before I came here, I was in a remote tribal area, where starvation deaths have returned for the first time since independence. Twenty people died in one week. In another region, 800. In Rajistan, 11 children in one week. The government has admitted that 50 million Indians are on the verge of starvation, while 60 million tons rot in the go-downs. Because the corporations must be allowed to control trade, there must be free imports, which depress the prices, so that the farmers are getting next to nothing back for what they grow. And the poor people cannot get access to food, because cheap, accessible food is treated as a drain on the budget. You know the story.

But just look at what has happened with 10 years of World Bank reforms. We used to spend 28 billion rupees on food subsidies, and the entire denial of food to the people was based on reducing this 28 billion-rupee subsidy. Guess what has happened in 10 years? We now have a subsidy of 140 billion rupees, except that it’s not going to feed the people, it’s going to store the grain, and it’s going to give subsidies to corporations.

Well, there’s a third kind of violence, to the earth, her people, to the creativity of farmers, and that I believe is in the new forms of property rights that are being created, called intellectual property rights. Patents.

I give you very little story. I come from Doon Valley, and Doon Valley is very famous for the best basmati in the world. Basmatis are aromatic rice. The name itself means ‘the queen of aroma.’ In 1987, a company in Texas called Rice Tec got a patent which claimed that they had instantly invented basmati as another rice line, and now onwards they would be the exclusive makers, producers, sellers, distributors of rice seeds, rice plants, rice grains. We had a four-year campaign against this Biopiracy, and we are happy to say that at least 90 percent of the claim has now been knocked down.

But it’s not enough. It’s not enough because we just did a computer search and found 2,000 patents on rice! One patent is for artificial rice, to take the waste from industrial agriprocessing, bleach it, and turn it into pellets! Another one about artificial basmati – that you take normal rice, you grind up basmati, and you give a coating to rice and sell it as basmati. These shouldn’t be rewarded as inventions, they should be punished as fraud!

After basmati, we now have a major campaign against all patenting of seeds, of plants, of rice varieties, and when I talk about rice varieties, it’s particularly important to us, because India was the home of 200,000 rice varieties before the Green Revolution. And in districts and regions where the Green Revolution came, all it would introduce would be one variety, which couldn’t survive more than two years, because the pests would wipe it out. And then they’d bring another monoculture, and another monoculture. Their diversity of industrial breeding is a diversity of collapsing monocultures. It’s like the choices in our supermarket: These are pseudo choices; These are pseudo diversities.

For us, the issue of diversity is the very condition of peace, and starting with my disturbance, my pain of what I learned about farming during those years when I was looking at the Green Revolution in Punjab, and finding out later that they wanted to give us a bigger gift of genetic engineering and patents and corporate control over our agriculture, as if we hadn’t had enough with the Green Revolution, I committed myself to saving seeds, and that’s what we started as Navdanya, the movement for saving seeds in India. We have through our small initiative now rescued more than 3,000 rice varieties, and our little farm like this [she indicates MOFGA’s Common Ground] grows 250 rice varieties. They’re in the field right now.

But even deeper than just the diversity of our crops I believe is the diversity of relationships between us and the earth, between different species, because only that diversity, complexity, and flexibility of relationships is a real response to generating security. We know when we have a monoculture it can get knocked out by one disease, by one pest. We know when we have centralized systems, it takes very little to bring them to a halt. Organic agriculture to me is the movement for peace, the deepest movement for peace, because it creates peace at that fundamental level where it rests on ecological security, creates economic and political and social security, and therefore doesn’t have any place for wars and violence and arms.

But there is another dimension to the peace making through organic agriculture, that it is by its very nature democratic. You cannot be an organic farmer and have Monsanto tell you exactly what to do: The earth tells you what to do. You cannot be an organic producer and not have relationships of a decentralized economy that this fair celebrates. It is that decentralized economy that creates conditions of peace. Centralized economies are based on militarized control; they create terrorist response; and they create deeper violence to contain that terrorist response. That vicious cycle will never end.

[Here, an interruption occurred to announce a dog in distress in a vehicle in the parking lot. “Sorry for the interruption,” concluded the announcer. “No, thank you for the interruption,” said Shiva. “Thank you on behalf of that dog. And that’s really what we need – interruptions that make us listen on behalf of those who can’t speak.”]

I want to, in closing, talk about where we want to go in creating a peaceful future, a future for diversity, diversity not just of all cultures and peoples, but diversity of all species, all beings. The first is: We have to say no to centralized control. We cannot afford control that is based on militarized technologies, militarized political systems of the kind that had to kill a youth, Carlo, in Genoa. But I can’t even begin calculating the numbers of people we have lost in trying to say no to corporate control over our agriculture. Eleven farmers were killed in Madhya Pradesh, three farmers were killed in Bijapur district in Karnataka. Besides the suicides. Every time farmers say, “We need a fair price; we need to be sure we can survive,” all they get is bullets. It is time to stop the bullets as the means to keep down democratic dissent that is showing us the way to a future.

From Gandhi we have learned that you cannot respond to violent systems with violence. But you have a duty to not cooperate with violence through nonviolent means. And that is what he meant by Satyagraha, the fight for truth. In his time, he led the Satyagraha against the forced cultivation of indigo for the British. It was used as a blue dye in those days. He led the Satyagraha against the British saying they would have a monopoly to make salt, so that they could run their armies with the revenues collected through that monopoly. And he went to Dandi Beach, collected the salt, and said, “Nature gives it for free. We need it for our survival. Your laws cannot come between us and our survival. We will violate your unjust laws.” And that is what triggered our freedom movement. Those are the kind of actions that allowed Indians to say we will govern ourselves, we will not cooperate with unjust laws.

We have had in India a renewal every year since ’91 when the GATT agreement was being finalized, and patents on life were being imposed on us, a commitment we’ve had to renew because monopoly laws on seed are being introduced in India under the force of the United States government, the WTO, the World Bank, and we’ve repeatedly said, “We will not obey immoral and unjust laws that treat life as an invention of corporations. We will save our seeds, we will exchange our seeds. We will not allow these duties to the earth and the future to be treated as crimes and theft.” Because that is what patents on seeds means: A farmer who saves seeds is a thief; a farmer who gives seed to the neighbor is stealing the intellectual property right of companies. And even the poor farmers like Percy Schmeiser, whose field was contaminated by Monsanto’s Roundup Ready canola, after his fields was polluted, he’s been asked to pay $200,000 for stealing the genes; and [it] doesn’t matter whether the wind or the pollen brought the genes to his farm. We cannot allow that kind of criminalization of our farming systems. We cannot allow our farming to become a dictatorship of police states working for the protection of the unjust property rights over life on earth.

But even while we say no to what we don’t want – you are doing it here, we are doing it in India – we are saying yes to the creative alternatives that do give the future a chance, life on this planet a chance. And those creative alternatives are what we all need to build even further, because that’s where you will overcome fear, you will overcome the mentality of violence and cultures of violence, because if there is a conflict today, it is between cultures of violence and cultures of peace. There is no other conflict in the world.

In India when we pray, we say, “Let all beings be happy. Let all beings be at peace. Let all beings be free of disease.” And when we say beings, we mean the grass in this field. We mean the pollinators. We mean all the species in those forests. I do hope that this country too will be able to go beyond the contemporary slogan of “God Bless America” to “God Bless the Earth.”

One of my favorite, favorite Indian rituals is the peace prayer, which we have every time we shift house, someone is born, someone dies, we have a peace prayer. And I love it because it’s not just about a country, a family, it’s about peace of the earth, may the peace of the skies, may the peace of the plants, may the peace of the atmosphere, may the peace of all beings of creation, of the creator, may that tremendously deep peace be with you.

[Standing Ovation]

I want to just share with you a few books you could look out for in your independent bookstore, books I’ve written, some of them have made it to this country through publishers here, particularly: Biopiracy, which is about the patent issue; Stolen Harvest, which is about the corporate takeover of our food systems – both of them have been published by South End Press, which will be bringing out in February my next book, which is called Water Wars – in which I track how our systems of agriculture that create water wasteful systems are at the heart of the crisis of water that the planet is facing. There also are other books – The Violence of the Green Revolution is being published by Zed Books and is available in this country; Staying Alive. We have reprinted [Sir Albert] Howard’s An Agricultural Testament, through which organic farming came from India to the U.K., the Rodale Institute, and the rest of the West. For those of you who don’t know, Howard was sent as the Imperial Agriculturist by the British to introduce chemicals to Indian agriculture. And he says in this book, “I came with my spray guns and saw no pests. And so I decided to learn from the pests and the peasants how to do good farming.” That’s what this book is about.

There are some monographs we have that you go to our web page [www.vandanashiva.org/]. This whole suicide story is in a report we’ve done called Seeds of Suicide.

There are other publications that are available. The Ecologist, The Resurgence – I encourage you all to look out for them at your independent bookstores — The Gulf of Maine Books in the Social and Political Action Area, will be ordering copies of books you might want to order — and I will tell my publisher to make sure they don’t take the kind of time they usually take in our part of the world to get these books in for you.

Thank you.

Just one more thing I remembered. Partly because we were getting so … you know, education was being replaced by propaganda of every form … we’ve decided in India to start a tiny little organization/institute/college on our farm, where we have seed saving, where we do organic farming, and we call it the Bija Vidyapeeth, which means the “School of the Seed,” which also means learning the seed … education, but learning from the seed too. I’m going to leave some flyers of the School of the Seed. The first course we are running, which is literally as I go back, is on learning from the South on sustainable communities. The second one, in winter, in December, is Gandhi and Globalization – How to Deal with Violent Societies Nonviolently. We have courses on holistic biology, we have courses on sustainable cities. Get in touch. The addresses are with Heather. I welcome some of you to return a peace journey to our country like I’ve made mine to you.

Vandana Shiva can be reached at [email protected] or at Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology, A 60, Hauz Khas, New Delhi, India 110016; Ph. +91-11-6968077 and 6853772; Fax +91-11-6856795.