|

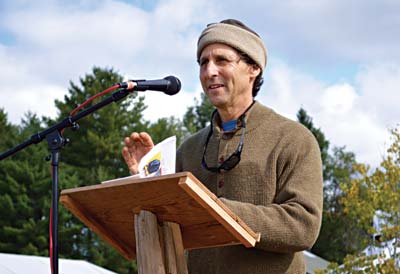

| Sole Food Street Farms, founded and directed by Michael Ableman, employs 30 people and produces 25 tons of food each year on large parking lots using an innovative moveable box system. English photo |

|

| April Boucher, Common Ground Country Fair director, presents a shirt to Ableman. English photo |

Street Farm – Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier

Sunday, September 25, 2016 – Common Ground Country Fair, Unity, Maine

Michael Ableman is a farmer, author, and photographer and a recognized practitioner of sustainable agriculture and proponent of regional food systems. He has written several books and numerous essays and articles, and lectures extensively on food, culture, and sustainability worldwide. Michael is currently farming at the Foxglove Farm on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia, home of The Center for Arts, Ecology & Agriculture.

Sole Food Street Farms is an urban agriculture social enterprise in Vancouver, British Columbia, that trains and employs people from North America’s original “skid row” who are managing long-term addiction, material poverty and mental illness. One of North America’s largest urban agriculture projects, Sole Food employs 30 people and produces 25 tons of food each year on large parking lots using an innovative moveable box system.

Michael Ableman, cofounder and director of Sole Food Street Farms, is one of the early visionaries of the urban agriculture movement. He has created high-profile urban farms in California and British Columbia; has worked on and advised dozens of similar projects throughout North America and the Caribbean; and founded the nonprofit Center for Urban Agriculture in the early 1980s. He is the subject of the award-winning PBS film “Beyond Organic.” His books include “From the Good Earth,” “On Good Land,” “Fields of Plenty” and the newly released “Street Farm – Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier.”

Ableman lives and farms on his 120-acre Foxglove Farm on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia. In his keynote speech at the 2016 Common Ground Country Fair (view on YouTube), he talked about his 40-year agricultural journey from rural fields to urban hardscapes where his work is now salvaging land and lives.

In the early 1970s, at age 18, Ableman joined a California commune that raised 4,000 acres of row crops, orchards, dairy goats and cows, grain and fiber. The commune supplied its own natural food store, bakery, juice factory and restaurant, and fed its members, who made their own backpacks, shoes and clothing. After four months there, Ableman was given the responsibility of managing 30 friends who tended the 100-acre organic pear and apple orchard that had been abandoned for 15 years. They pruned all winter, thinned all spring and harvested in the fall. The repetitive work was not drudgery, said Ableman, but more like an all-day party.

“The work got done, the orchard thrived, and those apples and pears gained a reputation around the country,” thanks in part to the cold nights and hot days of the high desert. “I am sure that fruit was equally infused with the energy of those people and the pleasure they found in each other and in that land,” he added.

This community experience informed Ableman’s subsequent agricultural endeavors and demonstrated for him that good food is more than just technique and fertile soil but also comes from people who love their land and bring great passion to working with it.

Most neighborhoods in U.S. cities at that time lacked jobs and food but had many abandoned lots. Ableman thought that small farms on those lots could employ people, provide food and improve the areas, so he started farming projects in Watts and Los Angeles, eventually developing a 12-1/2-acre farm and education center in California that produced 150 different fruits and vegetables, employed 30 people, provided food for 500 families and grossed almost $1 million at its peak. Due to development pressure in the early 1980s, this became the nonprofit Center for Urban Agriculture, placing the land under one of the first active agricultural conservation easements in the country. The easement preserved the land in agriculture, required specific social and ecological principles, and required community programs and place-based education on the land.

After constantly having to defend the farm’s right to exist and dealing with other struggles of farming in an urban environment, Ableman wanted to own his own land – impossible in much of California – so he and his family moved 1,200 miles north to Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, eventually settling on their farm.

He said he senses that the fields and surrounding intact forests are connected in ways he is just beginning to understand. When the fall rains come, mushrooms pop up everywhere. “I imagine this vast network of mycelium, miles of tiny threads, moving from forest to field, providing the underpinning for soil and plant health.” He senses “that we are part of a long chain of humans on that land, from the native people who fished its creeks and lakes, to those who built the original homesteads, to ourselves,” each link informed by the past and by the land. “I believe that land chooses and dreams us as much as we choose it. Everywhere I worked I was placing another layer on the layers of those who came before me, imposing my dream on someone else’s from some time in the past.”

When he thinks about land tenure now, Ableman realizes that “we’re all just passing through, temporary tenants and caretakers of a larger natural force, and all that will ultimately remain is the land. So the best we can do is leave it more fertile, more productive, more biologically alive, more diverse than we found it. And use our brief time to feed, nourish and inspire.”

In 2009, restless again, he cofounded Sole Food Street Farms in Vancouver to demonstrate that urban agriculture can be truly agricultural, and to reach out to people who needed help. A series of urban production farms grew in the downtown East Side neighborhood of about 15 square blocks inhabited almost entirely by people with some form of addiction or mental illness.

“It’s the poorest postal code in Canada,” said Ableman, and “has the highest rates of HIV, has incredibly high rates of poverty and prostitution. Our idea was pretty simple: Provide someone with meaningful work, and maybe other things might happen as well. This was not an attempt to get people off of drugs or to save anyone. They come together each day in parking lots and spend their day growing food for their community.”

This is not a make-work program, he said, but almost 5 acres of production farms supplying Vancouver with quality food.

Crops grow in 40- x 48-inch interconnected boxes that are stackable, that nest and that have plug-ins for hoops. The entire system is moveable.

“We get 3-year leases when we can,” said Ableman, from private landowners, slumlords and the city of Vancouver. Participating landowners get a 65 percent property tax benefit.

Maintaining organic matter, soil fertility and soil biology in a constrained system is difficult, he noted. Organic matter burns up quickly but is maintained with added compost tea, worm castings and other materials.

His new book, “Street Farm,” addresses the possibilities and hard realities of growing food on an agricultural scale in the city – how much food can be produced, how to address the physical, regulatory, social and financial challenges – and it gives a voice to those he works with, putting a compassionate face on addiction, mental illness and poverty.

The Vancouver farm focuses on crops that have a high probability of success. “Our staff was used to failure in other aspects of their lives,” Ableman explained. “To sustain the project, we needed immediate, sustainable, positive results.” Seven years later, individuals who had not previously held a job for any significant length of time had developed their skills so much so that Sole Food was voted the top food producer in the region.

The farm generates $300,000 to $350,000 annually in product sales, and Ableman fundraises for another $350,000 per year.

Over seven years, 75 people have been employed, and now 4-plus acres of pavement hold 8,000 growing boxes; a large urban orchard produces persimmons, figs, quince, apples, pears, plums and cherries; 25 tons of food are produced annually; and every dollar paid to the staff results in $1.70 in savings to the healthcare, legal and social assistance system.

Reading from his book, Ableman introduced Kenny, who has been with the project since the beginning, and described the hard-core addict’s awe “at handling a fragile tomato transplant that depended on him for its survival, as Kenny, too, was fragile.

“We have discovered,” said Ableman, “that the simple act of planting a seed, nurturing plants, harvesting food and feeding a neighborhood can produce incredible results. Our work is about recovery, of land and of people, one handful of seeds, one bucket of compost, one parking lot at a time.”

Another worker of several years, Rob, said Sole Food was “the best work experience I ever had in my life. I never woke up thinking, ‘I don’t want to go down there.’ And then my mom died and I made the same choice that I always do,” turning to drugs. But Rob had helped shape the farm, and vice-versa. He once said, “There was this one morning in the second season that says it all. It was 4 a.m. and we were standing on the farm in the middle of the city and I looked around and I felt like I was communing in church.”

Ableman said that Sole Food offers opportunities and builds community but cannot save people. “We are neither social workers nor therapists, we’re not physicians or psychologists. We don’t have the resources to hire such people, but we see therapy happening in other ways – harvesting carrots, seeding salad or radishes, preparing the soil for planting, hearing a loyal customer at the farmers’ market express pleasure in the food we provide. We believe in the power of growing food and feeding others as a way of healing ourselves and our world. Our job has simply been to set the table, provide the foundation for something to happen based on the belief that the simple fact of planting a seed can bring new life to the world.

“This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” he continued. “The obstacles are huge” and include a municipal code that was never written to accommodate large-scale urban agriculture, expensive permits, vandalism and theft – which he does not take personally. “We understand when someone is dope-sick or needs a fix, they will do what they have to do.”

Drug paraphernalia in and around the beds is a hazard. Workers wear gloves when cultivating some beds, and each morning they collect used needles from the ground and beds. “We have rigorous controls to ensure that the food we produce is safe,” said Ableman.

“I have no illusion that urban agriculture is going to feed our cities,” he added. “The more intelligent conversation is, what is the appropriate relationship between urban, peri-urban and rural agriculture? What’s appropriate to grow where? How do we develop and support each other? Urban agriculture is important for reasons beyond the food itself.

“I believe simple things can help in profound ways,” said Ableman. “Salvation can come from the soil, when you get your hands in it, when you learn how to maintain its nutrition and biology, when you cultivate it, keep it open, oxygenate it.” Likewise, “for you or me to stay well, you need to be well nourished and hydrated, to breathe deeply and to stay open.

“Giving someone a living organism to care for, something she can’t leave alone even for a day, something that depends on her for survival and wellbeing, gives that person a reason to live and stay well,” Ableman believes. “Sole Food was built based on the principle of rehabilitation through meaningful work. Growing food is high on the list of meaningful work.”

He knows that this work alone will not heal those who work with Sole Food, “but the raw biology, the simplicity and physicality of the work, the magic of seeds emerging, plants thriving, food being harvested … in places where there was previously nothing but hardscape, trash and rubble; this is recovery. Experiencing it will touch and change you.”

– Jean English