|

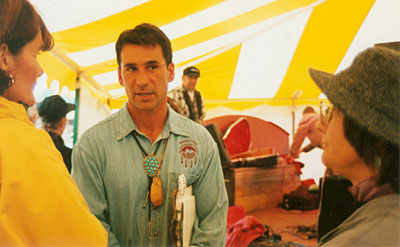

| Chief Barry Dana of the Penobscot Nation speaks with fairgoers after his keynote address. The simple Penobscot prayer, “All my relations,” symbolizes the Native view of nature, said Dana. English photo. |

Keynote Address by Chief Barry Dana at the 2001 Common Ground Country Fair

Barry Dana, Chief of the Penobscot Nation, grew up on Indian Island in the Penobscot River. A long-time participant at Common Ground Country Fair, he was a keynote speaker there this year.

While growing up, “for some reason I liked being in the company of elders,” says Dana, and thus he learned about canoeing, basket making, snowshoe making, hunting, gathering plants, and other Native traditions. “It was really great growing up where I was connected to my culture,” he says. “A lot of people today don’t have that opportunity. They feel connected to their culture but lack a lot of the opportunities that kind of bring it home, make it more personal.”

During his high school and college years, Dana was away from these traditions, but “it was always good to go back home and be connected to that,” he says. Later, while he was teaching at Indian Island, the shop teacher suggested that they make a birch bark canoe in school. “I’m supposed to be the one to have that idea,” jokes Dana. “I was the Indian! He pushed me and pushed me and finally set up a date to go up to New Hampshire to visit a guy who makes birch bark canoes.” After following bad directions, driving by the guy’s house three times, getting more directions – in French – and then deciding to give up, “I caught something way down this long driveway,” Dana says. “I … said ‘There’s Henry right there.’ My friend said, ‘How do you know it’s Henry?’” According to the directions they’d received, this made no sense. “I said, ‘Trust me, that’s Henry.’ Seeing him sitting there carving with a crooked knife was what I saw, and it took me way back to my childhood, watching people work with crooked knives.”

Dana uses this story to illustrate the need “to have an experience” with something in order to be connected to it – and the fact that his life experiences came from growing up “with people whose livelihoods and their culture and their traditions are directly connected to nature.”

Dana got his college degree in forestry, but thought that he’d “like to do more with trees than just cut them down and produce things … There’s a lot about forestry that builds that up, but basically the nuts and bolts is producing products.” So he got a degree in education, then worked as a probation officer on the reservation. “I worked with kids, and I decided that really what’s missing in their lives was culture. So we created these canoeing trips, these camping trips, we climbed Katahdin,” and that started him on his pathway of working with people by using his own life experiences. He notes that none of the people he worked with as a probation officer is in jail today, all have productive jobs, “so I think it works.”

Still, he wasn’t sure what his life’s work should be at that point. “So I did what was recommended by one of my elders, and I went to the mountain and I spent four days there … to get a vision. You hear about all these great visions. Well, I was a little nervous, because the Micmac elder said, ‘Yeah, I did that vision quest, I fasted 21 days and I didn’t see a damn thing.’ So I was a little nervous. But I did my vision quest, I came back, and people said, ‘What happened?’ I said, ‘Not much. I had a good time, I lost some weight … ’ but it takes time if you’re not truly connected with that philosophy day in and day out … And it takes time to reflect on it. Over the time, I was able to realize some of the things I did see up there, and one of them was this massive group of people had been with me. So from that, one of the elders said, ‘You’re got to bring people to the mountain.’ So my life has been not just going to the mountain, but the purpose of going to the mountain. Why do Penobscots, Passamaquoddies, Maliseets, Micmacs go to the mountain? Vacation? Just for a picnic? No.” Rather, their legends “talk about our connectedness with Katahdin and it being the origin of our people. That’s where we come from and that’s where we return to.”

In this spirit, about 20 years ago, the Penobscots started an event called the Spirit Run to the Mountain, or the Katahdin 100 – a 100-mile endurance event that starts at Indian Island and goes to Katahdin. This year 191 people participated. “Some of us ran the entire 100, some of us relay, we bring family, we bring friends, and it’s a community tradition now.” The event connects participants not only to the mountain, but to “everything we see along the way. As you’re traveling in the river, which is what I do, you’re paddling against the current, you’re paddling into these clumps of grass that float on top of the water. You know, if you drive down Route 2 and you see the river, you say, ‘Oh, isn’t that pretty!’ But if you’re in the bow of a canoe and you’re paddling with your head down because you have a headwind, and all of a sudden this clump of grass gets stuck in your bow, and you have water spraying up over the bow that slows you down, all of a sudden things aren’t so pretty. But we don’t quit, we keep going. It’s considered one of the gifts. One time we had thunder and lightning. That’s okay. It’s considered one of the gifts. Shallow water, extreme headwinds … it’s all a gift of nature. It’s kind of like your birthday – You don’t always get the gift you want.”

Dana talked, too, about the Unity Conventions that he went to in Oklahoma and Canada when he was a teenager. “The underlying theme was, you need to learn your culture, you need to retain your language, and you need to learn how to live with the land, because there’ll come a time when … the survival of the human race will depend on that knowledge. Over the course of my adulthood, I never forgot about that, and I think the reason why we’re all here today at organizations like this is that we see that … those prophesies that the Native people talked about hundreds of years ago are coming true today.” Dana is living the theme of these Conventions. “My connection to nature … it’s not just a one-time experience, or one weekend or one week. I try to make my connection to nature be a lifestyle, something that my whole philosophy is drawn from.”

Teaching Traditions

That connection with nature and culture is something he taught for 14 years at the Indian Island Elementary School. “I had a schedule. From 8 to 8:40, I had this, from 8:40 to 9, I had this … and so on and so on, and I was in heaven, because I was teaching my own kids their culture. I was so excited. I was sitting with an elder while I was beaming about this course I had in school where I was teaching basket making, sweetgrass braiding, you name it, I was doing it. He said, ‘Gee, that’s too bad.’ Someone with me thankfully said, ‘Why do you say that?’ He said, ‘If you need to do it in the school, it means it’s not getting done in the community.’ And he was right …. A parents’ group … said it’s not being done at home, it’s not being done in the community, so it needs to be done in school at least.”

After 14 years, however, Dana tired of rushing through schedules. “I remember one particular kid, he happened to be my cousin, he didn’t get excited about anything in life … he was just kind of going through life. When it came to culture time, though, he was into it. It might take him 20 minutes to get into it …” Dana would have to ask him, “What were you working on last time?” “Oh,” he’d reply, I was working on a canoe.” “Where is it?” “I don’t know.” Dana continues, “Basically it was wherever I put it away for him last time. So he’d find it and I’d say, ‘Okay, get your tools.’ He’d say, ‘Yeah.’ But once he got them, once he got working, it was hard to make him stop. That was my personal conflict with education, with its schedules. I had to move on.”

At the same time, Dana was getting inquiries from groups and individuals off the reservation who wanted similar cultural experiences. “I thought, wow, I don’t know about that – excuse the expression, my wife says it’s okay – I don’t know about working with white people.” His wife tells him, “Well, I am white, you can say that.”

“So … I had to work through a process in my own head that made it okay to work with non-Indians. It sort of came back to me … well, wait a minute, this is what those elders were talking about. It wouldn’t just be Indian people doing the stuff …. All races would take seriously the teachings of the earth and want to use those teachings to help save the planet. I figured underlying the skills, underlying the need or wish to make a basket or track a deer or make a drum, underneath all that was a common thought amongst all people who wished to become connected to nature, connected to what seems to be right, and it seems like the Native view was the closest view in this area that made that possible. So I sort of became an instrument by which that happened.”

The Earth Is Our Mother, the Rivers Are Her Veins

Dana explains that all animals in the world have a role to play, but humans get confused and thus create problems. “If we walked in balance with nature, if we studied nature, it would be really easy to figure out that if you put that dam across the river, those fish aren’t getting up …. For complacency or comfort, we’ve become disconnected to nature.”

Having grown up on Indian Island, Dana says that nothing symbolizes nature or his tribe’s importance to him more than the Penobscot River. “If we view the earth as a mother, and if we view the river as veins of mother earth – excuse me a little bit here – then why in hell would we ruin it? Why would we dump pollution in it? Why would we allow pipe after pipe dumping harmful chemicals into that river? Why? Because we have comforts and we need those comforts. We need paper, we need electricity.”

He allows that people may not have realized the repercussions of their actions toward the river in the past, but today, “We know it’s a problem, and it’s humans out of touch, out of connection, out of balance, who did it. Now it’s up to humans to be in touch, to be connected, to fix what was wrong, what’s broken.

“So we’re the caretakers of the earth, every one of us. We have a job.”

How do we do that job? Not by just telling others that they need to be connected. “You need to feel the harmony of the earth, you need to do this. You just play games with [kids] that put them in touch with nature. You teach them skills, like making a shelter out of leaves, and the kids say, ‘Oh, that’s fun!’ and you realize they’re connecting.”

This is how Dana himself grew up, watching his grandmother braid sweetgrass; hiking “up in the woods.” He adds, “It’s hard to find them today; now it’s like ‘up in the housing development.’” But in his youth, he would go into the woods “just to be out there in nature. When you take a four-day canoe trip, when you just eat a sandwich along the banks of the river, or when you really get into it, when you do more, like draw your life from the land, whether it’s basket making or planting or whatever, then you get to know the earth, and when you know the earth, you’re connected.”

He concedes that not all Native Americans would say what he does. “My mother says that’s all great, she grew up doing this kind of stuff. ‘You’re not finding me in a canoe these days,’” she tells him. “‘And I’m just as happy to drop a few dollars on the counter and get my food, because I remember having to grow it, hunt it, shoot it and all that stuff.’” Many others, however, have kept Native traditions alive.

Dana apologizes in advance in case he doesn’t connect with some audience members, then says, “If you’ve downed a moose and you’ve skinned it and you’ve flushed its hide, that’s like nothing else. There’s no substitute. Flushing a moose hide is … flushing a moose hide. Scraping ash is scraping ash. Listening to the hum of the vibration of a braid of sweetgrass ….

“My grandmother,” he continues, “used to braid so fast, and she’d have two pieces in her mouth, and she’d still talk and she’d smoke a cigarette and without missing a beat, she’d grab an extra strand, throw it into the braid and keep braiding, and then wrap it around the back of the chair. She would do that until she had a hundred yards of grass braided all together in one braid. And … where you splice [the sweetgrass] in there’s a little extra piece, she’d break it off and put it in the ash tray, and the cigarette would catch that, so her whole house would be filled with burning sweetgrass, so it was quite a sacred time for me.”

Different people can have these experiences on different levels, says Dana. “Somebody came to me one day and said, ‘Yeah, I really want to make a drum,’ and I looked at this person and said, ‘I don’t think so.’ I was reading this person and ended up being right. I’m not always right, but when I make a drum, it’s taking the hide off of a moose, and I put it in the freezer and I save it until we do a drum class. And that means flushing it, taking the meat and fat off, it means sweat, it means maybe some unpleasant smells. And this person said, ‘Yup, I really want to make a drum.’ I said, ‘Did you ever flush a moose hide?’ ‘Oh, my goodness, No!’ And I said, ‘Would you like a drum?’ ‘Oh, yes,’ So I directed this person somewhere else where the skins are all prepared, the wooden hoop is all prepared, and you basically, in two hours time, you lace it together and you leave happy with your drum.

“So there are different levels. It’s just that my level, having grown up where I grew up, with my uncles who are really hard core when it comes to a lot of these activities, shaped my philosophy. If you’re going to make a drum, the best way is … to come with me and you’re going to shoot a moose. One person said to me, ‘Oh, I could never shoot a moose. How could you do such a thing?’ I was in a group of guys. My brother said, ‘It’s easy. Point and shoot.’

“There is this disconnection,” says Dana. “People, when they ask these questions, they don’t have lists of those experiences, where your whole culture, your whole identity, has been based on these activities of shooting a moose, taking a deer, netting salmon, drawing things right from the earth. And until you do that, it’s really difficult to get a full appreciation.”

The Spirituality of Politics

According to Native philosophy, says Dana, politics is the highest form of spirituality. In contrast, U.S. politicians are often the butt of jokes and negative comments. But for Natives, “our politicians are our leaders. Your chief is your number one person. If there’s an arrow coming, they’ll be the first one to take it.

“In Native philosophy, in politics, we try to instill spirituality. So if we’re taking on issues like the river, we’re taking on issues like sovereignty. These aren’t simply political items, they become an essence of who we are as a people …. Without that feeling of brotherhood, without that feeling of understanding, how can you make a choice, how can you make decisions that affect everybody? If you were making choices that affect the river, then that does affect everybody. It affects … 11 species of fish.

“If you bring in the spirituality of a river people, and if you were to say we’re going to make decisions on this river, we’re going to decide whether or not we’re going to allow these permits that allow so many parts per whatever to pollute the water, and we’re going to allow the permits to continue for another 30 or 50 years with the dams …. If you are a river people and … you really understood the people who lived there, I think the choices in government affecting that river would be a lot different. It would be an easy decision. Who’s going to give out the permits to that river? Permits to do what? Permits allow pollution, we need to remember that.”

Dana discusses his tribe’s court case, because it highlights this connection between spirituality and politics. “We were asked by three paper mills to deliver documents relating to water quality and many other issues.” He read in The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener [Sept.-Nov. 2001] that the tribes weren’t willing to share documents relating to water quality. “Not only did we offer to share them,” he emphasizes, “we’ve called meetings and we’ve talked to mills. We’ve worked with the mills. We’ve worked with the Department of Environmental Protection in the State of Maine. We’ve sat at the same table and we’ve fought over things. We’ve shared a lot. What we’re not willing to do is be forced into state court by lawyers. That’s what it all boils down to is lawyers trying to push state laws on tribes. That’s the difference …. We’re not going to give documents because someone said we had to. We’re a tribe, we’re a Penobscot nation, we’re not a political subdivision of the State of Maine, otherwise known as municipalities. You cannot ever instill that in a Penobscot mind.”

Dana says that the mills don’t want the documents. They have been given the same documents by the Attorney General’s office. “It’s not about what’s in the documents, it’s not about water quality, it’s about the mills or the lawyers for the mills using their power … to maintain status quo with the State of Maine, to make sure that the powers that be maintain their avenue by which they keep us in the dark.”

In five years, Dana continues, one mill had 33 violations. “If you’re given a permit to drive a vehicle and you violate that permit, you’re assessed a fine, so these mills were assessed a fine. But what happens three or four violations down the road?” he asks. “You lose your license. These mills continue to operate. They just are assessed, quite often, minor fines, and the following year they are given that exact same dollar back in tax rebates.”

Despite being brought into court and having to fight for tribal sovereignty, Dana says, “We’re willing to not only share our information but to keep the door open for our communications, because … even more important than tribal sovereignty is the river. Take away the river, there’s no more river. So … in honor of future generations of this river, we’re now hosting a meeting of the state Department of Environmental Protection and the State of Maine and the mill owners to sit down at the same table and talk about the river. No lawyers.”

The river issue is symbolic, says Dana, of all views of nature, not just of the Penobscot or Passamaquoddy view. “It’s important to everybody living in Maine, everybody who’s ever thought that a river is a beautiful thing, everybody who agrees that the river needs to be preserved, not for human use ….”

Dana says that he used to be standing on the “I” soapbox. “I want to go fishing, I want to go hunting, I want to gather plants. I, I, I should have the right to conduct these activities because it’s part of my culture. I was standing on that soapbox for a long time, it got a lot of mileage.” Now, however, he sees “something of a higher nature than that, and that’s the river itself. The river needs to be as nature intended it: free flowing, free of pollution.”

A Closing Prayer

A simple but powerful prayer is often used to close a Penobscot meeting. “We close by saying, ‘All my relations,’” says Dana. “That one phrase, those three words, symbolize the Native view of nature. All my relations is all my relations: trees, birds, all winged animals, rocks, rivers …. ” He said that the phrase, “The earth does not belong to us, we belong to the earth,” helps make that point. Then he closed by saying, “Mezin-dul-na-bem-uk” [All my relations in Penobscot], “All my relations. Thank you very much.”