|

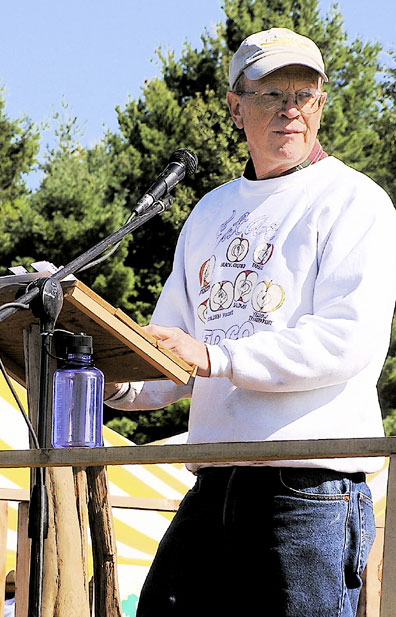

| In his keynote speech, John Bunker talked about the history of the apple trees of Palermo, Maine, and about his history with those trees. He noted: “As we navigate into the future, our rich agricultural past can guide us, and with the tremendous challenges ahead, trees become more relevant than ever. When we plant any tree, we express our gratitude and pay homage to the past by giving a gift to those who will follow.” English photo. |

by John Bunker

Good morning.

I will begin by reading an excerpt from my book, Not Far From the Trees: A Brief History of the Apples and the Orchards of Palermo Maine 1804-2004:

Interestingly enough, like all but those Mainers of native ancestry, apples are also from away. Far far far away. Not from Massachusetts or New York or even California, but from half way round the world, in the Tien Shan mountains west of China in Kazakhstan, a place with the same latitude as Unity Maine, near a city with the odd name, Almaty, which fittingly means, Father of Apples. Even today there are forests of apples in the Tien Shan Mountains. Not orchards but forests.

So how did the apple get to Maine? Long before the great shipping fleets of Europe, stretching over 5,000 miles east to west and criss-crossing Asia was a vast network of trails and roads we call the Silk Road, connecting all the great middle eastern cities of antiquity with one another, and connecting China and India in the east with Europe and Egypt in the west.

It so happens that the Silk Road passed right through the apple forests of the Tien Shan mountains and the apple was able to hitch a ride on the backs and in the guts of camels and horses and tradesmen and travelers. Off it went to Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt, Turkey, Russia, Greece, Italy, Spain, and northward, so that over time, the apple became established in all of Europe,

Eventually, packed in wooded barrels, it first traveled across the Atlantic Ocean over 400 years ago in fishing boats to the Gulf of Maine. There sailors tossed their cores and even planted seedling orchards on the islands long before the pilgrims landed farther south on Plymouth Rock.

I say seedling orchards. I should digress for a minute to note a little botany. Nearly all apples are self-sterile, in other words they will not pollinate themselves. The pollen from one McIntosh flower, for example, will not pollinate any other McIntosh flower, even if it’s on a separate tree. No pollination means no fruit. However, they will accept pollen from nearly any other apple variety, wild seedling apple, or crabapple. All that’s required is that the apples are different.

The fruit on a McIntosh tree will always be ‘McIntosh’ no matter what pollinates it, but the seeds are a different story. Every seed in every apple will be a unique combination of its two parents. If you plant an entire orchard of McIntosh seeds and let them all grow to maturity, every one of those new trees would produce its own unique apples – none of them McIntosh. Each would possess some traits of both their parents, but each would be unique.

The ease with which apples cross and create new seedlings has had enormous significance in the history of apples and orcharding. For one thing, it means that apple trees grown from seed will endlessly produce new and unique apples. It also means that the orchardist must find another way to replicate desired varieties.

Many centuries ago some Einstein of the past invented grafting. By grafting (splicing) a small piece of a one-year-old apple twig, called a scion (sigh-on), onto another tree called a rootstock, the grafter can replicate McIntosh – or any other variety – by the dozens or hundreds or thousands or millions.

Until relatively recently – say about 1830 – nearly all American orchards were of the seedling sort. Back then there were few roads, no nurseries, often no stores. Travel was mostly by boat or by foot. You can fit a lot of apple seeds in a very small pouch. And so the immigrants planted apple seeds. Millions of seeds in millions of orchards from Maine to Ohio. Every orchard different. Every tree unique. Occasionally an apple proved to be of superior quality and was grafted around the neighborhood and given a name. We were a society of Johnny Appleseeds.

As Americans, we are often told that we are free. In fact we like to think of ourselves today as free, but most of us are utterly dependent on Hannifords for our food. We depend on Chevy and Toyota for our transportation and the Middle East for the fuel even to get us here today. We depend on Netflix and ESPN for our entertainment. Our ancestors cupboards and cellars were full of food they produced themselves. They traveled in vehicles they built, powered by horses and oxen they raised. They did not have to go long distances to find work. They worked at home. They created their own entertainment. They lived with an independence – and an interdependence – few of us will ever experience.

If you added up all the time you and I have spent commuting and driving off to this and that, it would amount to hundreds of hours a year. Think what we could do if we had that time. They did.

And apples played a key role in that independence. These early Mainers did not eat oranges or bananas or chips or soda. They ate apples and drank cider. Their orchards were not orchards like those today. These were small orchards, tiny by today’s standards. A large orchard 200 years ago would have been 150 trees. A typical 15- to 25-tree orchard made it possible to have fresh fruit from late July until June.

Which brings me to the question that I am most often asked: Which apple is my favorite? The implication is, I would say, that some apples are bad and some are good. I do have my own personal favorites, but that’s a matter of “each to his own.” A better question I think is, not: is this apple good or bad, but rather what is this apple good for of bad for. That’s a great question because all apples are good for some uses and not so for others. In fact some are really bad for some uses. Each apple has it’s own nature.

The odd-flavored so-called “sweet apples” had no acidity. They were used to make molasses back when sugar was too expensive or not available. Those apples were first pressed to cider, then the cider was boiled down to a thick sweetener. These same sweet apples boiled and then served with fresh raw milk were considered to be highly medicinal. Yet if you ate a Tolman Sweet or a Pound Sweet today, you might wonder why anyone ever bothered to grow them.

For the best pies, use tart apples that intensify in flavor and maintain their shape after baking, such as Wealthy or Gravenstein or Scott’s Winter.

For best sauce, use varieties that cook up quickly on the stove. I can make up my daily batch of applesauce in less than 5 minutes with varieties such as Duchess or Somerset of Maine or Kavanagh.

For fresh eating, or “eating out of hand” as they say, the best varieties have unusual and distinctive flavors and a good balance of sugar and acid, such as Starkey or Garden Royal or King of Tompkins County or whatever your personal favorite might be.

Even the small, astringent apples we often find in the woods or by the side of the road were highly valued. They of course make the best fermented cider. It’s not a coincidence that the old timers in Maine still often call the small runty wild apples “cider apples.” They were pressed into cider and several barrels were stored the in basement of every home.

Some came on early, like Red Astrichan or Yellow Transparent or Sweet Bough or Chenango Strawberry. These apples were set right outside the kitchen so you could keep an eye on them and grab them before they went by. Others ripened in October and even November. The latest varieties were stored all winter and into the spring in the root cellar.

Apples were fed to the cattle, the sheep, the hogs and the horses. They were fried, and baked, and boiled and steamed and dried. Apple pies, apple cider vinegar, apple honey, apple custard, apple snow, apple fritters, apple float, pudding, dowdy, cake, pickles, sauce and on and on and on. Every apple was good. That is, good for something.

By the mid-nineteenth century there were well over 10,000 named apple varieties across the eastern U. S., hundreds right here in central Maine. Sometimes we think we have more choices than our ancestors.

I mentioned that in 1850 Palermo’s population was at its greatest ever. At that time we grew nearly all our own food right there in town. The same was true all over Maine. As recently as the Great Depression of the 1930s, when many Americans were starving, many in Maine were doing rather well. They were cash poor by our standards, but were well fed, clothed and warm. These farming ancestors understood that wealth is not something you hold in the bank or the stock market. Rather it is your land, your buildings, your livestock, your trees, your community. In other words, your ability to produce and care for your own family.

When I arrived in Palermo in June of 1972. I knew nothing about farming and I knew nothing about Palermo. Although nearly everyone in town had grown up on a farm or remembered their family farm, by that time, the period of small diversified farms had come to its inevitable conclusion. Many barns were sagging. Many had burnt, never to be replaced. Some farms were abandoned. Most dooryards were empty during the day when the kids were off in school and the adults had driven away to work. How was I – a kid from the suburbs of Boston and San Francisco – to learn about agriculture? From whom was I to learn?

Everyone remembers Dorothy and how the Scarecrow spoke to her and guided her, or how in the classic Disney films the mice or the rats or the trees teach the hero valuable lessons about life. Well, it happened here too.

Apple trees typically live to be 100 and sometimes 150 or even 200. When I arrived here, all over town were huge old apple trees still in their prime. These trees had in them nearly all of Palermo’s history. Most of these trees were still pumping out beautiful crops of fruit, blissfully unaware that the days of farming were over. For them it was simply business as usual. So they weren’t a bit surprised when I showed up in the fall to pick their fruit. They were only surprised at how little I knew.

There I was, a 21-year-old kid in Palermo with a bunch of centenarian teachers: the apples of Palermo. And so they taught me: about location location location. That fruit trees are like solar panels, converting sun into fruit. About soil; air drainage. About the miracle of water. About reaping what you sow: About the importance of fertilizer, pruning, mulching. About patience and the value of staying put in one place for a long time. About waiting until fall comes around again. That some years produce big crops and some years not. About gratitude for the fruit itself. For those who died long ago who planted the trees I was able to enjoy. And by extension, for those who cleared the land and laid out the roads and created the town. About the gift of the past we so often take for granted. And about service. To plant and plan for those who are not yet here and who I may never know or even meet. But they too deserve to have apple trees waiting for them.

The trees also introduced me to people around town. I would stop by a tree or an old orchard and next thing I knew I was meeting someone new.

“My visit with Papa Glidden that day was the first time I had met someone of the older generation who had grafted trees here in town. It was my strongest link yet to the orcharding tradition. I still recall my amazement and near disbelief when he explained to me that he had grafted the old Nodhead tree I had picked that afternoon. He took me back to his woodshed and showed me his grafting “kit” which, as I recall, consisted of a knife, a wax melting can, some string and some odd chunks of Trowbridge’s grafting wax. He would dip strips of two inch cotton cloth into the melted wax and then wrap his grafts. A year or two later I grafted a Nodhead scion onto an apple seedling in my front yard. That tree is now twenty feet tall and bearing this fall for the ninth or tenth year.”

And the people I met taught me the names of the old varieties:

My life became shaped by apples. I learned to graft. I planted trees in my own yard, many of them grafted from trees around town. I started Fedco Trees and began selling trees though the mail, many of them the old Palermo varieties.

I set off on a search for the obscure local apple varieties that originated throughout Maine. That search has taken me to every part of the state and introduced me to hundreds of people of every walk of life. Not only do apples love Maine, but Mainers love apples.

And the search goes on. Fortunately apples are patient creatures. Many ancient unidentified trees are at this very moment laden with fruit and waiting patiently for you or me or someone to come along and rediscover their fruit and reconstruct their story. We have started an orchard of these Maine varieties here at MOFGA. Visit them. They are planted on standard trees and will be here at the fair welcoming your great-great-grandchildren.

I should mention here one of my other favorite Maine institutions besides MOFGA. Some years ago I stumbled on the Palermo Historical Society one evening and was instantly hooked. What a perfect way to connect the past with the future. I became a huge fan of historical societies. After all, Maine’s past is an agricultural one. And many of us hope that its future will be one as well.

In 1950, J. Russell Smith published Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture. For decades this one book has been an underground inspiration for those seeking alternatives to the wasteful, shortsighted, destructive practices of modern mainstream agriculture around the world. Twenty years ago Bill Mollison coined the term permaculture. Today there is much talk about sustainable, biodynamic, edible forest gardens, carbon sequestration, and of course organic and local.

This past year was a weird one in central Maine. After receiving the most snow in recent memory, we were treated to a severe drought in spring and early summer, followed by relentless rain and a parade of thunderstorms. The drought, the snow, the rain, the hail, the floods all reminded me of the essential role that trees play here on earth. Trees are the water towers and the irrigators of nature. Their sapwood is saturated with water. An apple tree will expire thousands of gallons of water a year. A good size red oak can expire 40,000 gallons a year. Tree roots soak up run-off, hold soil and prevent erosion. Land absent of trees becomes land without water. Land without water is what we call desert.

Trees also store vast qualities of carbon. They take CO2 from the air and convert it to wood where it remains for decades or even centuries. Although estimates vary as to how much carbon a typical American adds to the atmosphere and how much a typical tree collects and stores, we do know that by weight, a tree is 50% carbon. It adds up.

Vast amounts of carbon and water are also stored below the surface of the earth in humus. Where there are trees, the surface of the earth becomes a thick, moist, cooling mulch of leaves, twigs, roots, branches, stumps and trunks. The roots of living trees weave through and tie the mulch together creating a rich carpet of humus.

Even if we wanted to do so, we can never go back to 1850 or 1750 or even 1999. But as we navigate our way into the future, there is much that our rich agricultural past has to guide us. And as we face the tremendous challenges ahead, trees become more relevant than ever. When we – like many thousands of others long ago – plant an apple tree (or any tree), we express our gratitude and pay homage to the past by giving a gift to those who will follow us.

I’ll finish with this from my book about my next-door neighbor who passed away a year ago:

“One crisp fall day many years ago Bob Potter harnessed up Prince, climbed up on the big Belgian’s back, and began to ride him down the Jones Road. He did not tell me what they were up to. Perhaps they would be twitching wood. “We were heading over to the other farm. All of a sudden that horse stopped. I said, ‘Prince, what’s the trouble with you?’ The horse stood still. ‘Prince, what’s the trouble with you?’” After a minute Bob looked up and saw the apple branch hanging above them. He had fed his horse from that limb a year before, and Prince, of course, never forgot. Bob reached up and plucked an apple. “OK Prince, let’s go.” And off they went.”

Thank you.