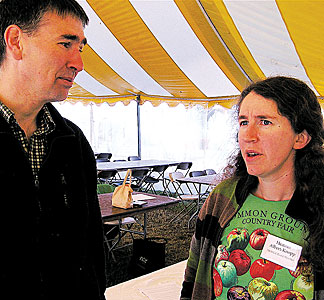

A MOFGA Public Policy Committee teach-in at the Common Ground Country Fair addressed this issue. Panelists included Dr. Tim Goltz, a family physician in Damariscotta; Karen Kleinkopf, a first grade teacher and co-founder of FARMS (Focus on Agriculture in Rural Maine Schools); and Heather Albert-Knopp, a MOFGA board member and administrator of College of the Atlantic Sustainable Food Systems Program. Heather Spalding, MOFGA’s associate director, moderated the discussion.

Goltz, who also serves on the MaineHealth Healthy Weight Workgroup and chairs the MaineHealth Preventive Health Workgroup, said that obesity is an extremely important health issue; that the best treatment for obesity is prevention; and that obesity prevention is the responsibility of multiple groups in society.

Weight is classified by Body Mass Index, or BMI, which is weight (kg)/height2 (meters). This measure is imperfect but is easy and inexpensive to get and works for most people. The ranges for adults are:

| < 18.5 | underweight |

| 18.5 to 24.9 | normal, healthy weight |

| 25 to 29.9 | overweight |

| 30 or higher | obese |

| Children are grouped according to percentiles: | |

| < 5th percentile | underweight |

| 5th to <85th percentile | percentile normal |

| 85th to <95th percentile | overweight |

| 95th percentile and greater | obese |

Far more than 5 percent of kids are obese, however. These classifications were set based on weight distributions around 1970.

Goltz shared data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC; www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/index.html) showing changes in the number of overweight and obese adults over time – based on self reports, which are usually about 5 percent off (with people saying they’re taller and thinner than they actually are).

In 1985, the average obesity rate for adults in the United States was 15 percent; by 2008, it was 33 percent. For kids, obesity rates have risen steadily, from 4 to 5 percent in the early 1960s, depending on the age group, to 17 to 18 percent in 2003 – and they’re still growing.

In Maine, 33 percent of children entering kindergarten are overweight or obese, as are 61.5 percent of adults.

|

| Getting fresh, local, organic foods to all people is part of the solution to the obesity problem, said Dr. Tim Goltz at a teach-in at the Common Ground Country Fair. Heather Albert-Knopp described efforts underway to do this. English photo. |

Why Care?

Obesity is not an issue of aesthetics, said Goltz, but is closely related to health. Diseases linked to obesity include diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, sleep apnea, asthma, gall bladder disease, heartburn, and breast, colon and pancreatic cancers.

The CDC estimates that a child born in 2000 has a one-in-three chance of developing diabetes during his or her life. Now, 23.6 million Americans (7.8 percent of the population) have Type 2 diabetes; 54 million American adults have prediabetes (their blood sugar is above normal but is not quite in the range to meet the definition of diabetes); and 2 million teens have prediabetes.

“When I started my medical career 15 years ago, that was just unheard of, and now it’s just exploding,” said Goltz.

“Since 1990, each year the incidence of diabetes has increased by 5 percent.”

A diagnosis of diabetes reduces life expectancy by 12 years and increases annual medical costs by $10,000.

A Maine Health study found that the incidence of overweight and obese people cost the state $2.56 billion per year, Goltz continued. The New England Journal of Medicine said a few years ago that the generation of children being born today is likely to be the first with a shorter life expectancy than its parents, as a result of overweight and Type II diabetes.

Causes

“In some ways, the cause of obesity is really simple,” said Goltz. “People are consuming more calories than they burn through basic metabolism and physical activity.”

In other ways, he added, it’s complicated, because so many factors affect people’s decisions about what and how much they eat and how active they can be. Economic factors also play a role. Through government subsidies, bad food has been made cheap and good food has generally been made more expensive. Each year, manufacturers of processed foods spend $32 billion in advertising, while the budget for the national five-a-day fruits and vegetables program is only $4 million.

A lack of sidewalks and bike paths is a problem; and, said Goltz, losing weight is very hard once it’s gained.

Physical activity has decreased as we’ve become more dependent on our cars. And parents, as described in the book Last Child in the Woods, have become afraid to let their kids play outside.

The Western diet, which tends to be low in fiber and high in processed food-like products, saturated fats and simple carbohydrates and is fortified with the nutrient of the week, is another part of the problem.

Everybody has a role in fixing this problem: government, through its policies; health care providers; patients and their families. “Clearly,” Goltz concluded, “farmers have a role to play too, because the key thing is getting fresh, local, organic foods available for the whole population.”

|

| Karen Kleinkopf co-founded FARMS (Focus on Agriculture in Rural Maine Schools) to bring quality food to students. English photo. |

Bringing Good Food to Schools

Kleinkopf discussed the role of FARMS (Focus on Agriculture in Rural Maine Schools), which she co-founded, in promoting increased use of locally grown organic foods in public schools, and strategies for working with food service directors, parents, administrators, teachers and students. Kleinkopf taught first grade for 10 years and, with her husband, Tim Goltz, has three young daughters.

As a teacher, Kleinkopf learned what kids eat, how they write or read, how much TV they watch, how much exercise they get. “When we had our own children, I said, ‘It’s all of our responsibility to be out there helping people and kids.’ Tim would have his medical journals lying around, and there were all these articles about obesity, and I started reading them as well.”

When their oldest daughter started school, Kleinkopf noticed a vending machine in the school. “Twenty years ago there was no obesity,” she said, “and 20 years ago there wasn’t a vending machine in the school.” She soon learned that the vending machine wasn’t going anywhere – in fact it’s still in the school.

Parents started asking about the school food, however, and a teacher told her the kids were getting chocolate milk 15 times a week. The school menu even included chocolate milk poured over frosted flakes, and chicken nuggets. “I don’t serve my child chicken nuggets,” said Kleinkopf, “so why are the schools serving her chicken nuggets?”

She and other mothers wrote an “awareness letter” urging more fiber and less sugar and sodium in school foods. “We were called into the principal’s office,” Kleinkopf said.

This precipitated relationship building – with the food service director and staff, the business manager, the superintendent.

“When we think of serving chocolate milk to our students, we think of making money for the school,” said Kleinkopf; “but we don’t think of the $2.5 billion of yearly costs of obesity for the state of Maine alone.”

Kleinkopf and others started working with Amy Winston (an economic developer for Lincoln County) to form FARMS, to educate students about good nutrition and the role of local farms in promoting healthy, sustainable communities, and to promote and facilitate farm-to-institution purchasing.

Meanwhile, after the Maine Harvest Lunch was revitalized in the Gorham area, “we decided to have a harvest lunch,” said Kleinkopf. “We just had our fifth harvest lunch.”

Originally volunteers organized the lunch. Now it’s institutionalized: The food service staff orders the food, and the farmer drops off the food. In the beginning it was grant-funded; now the school has taken on the program.

Kleinkopf now does school-wide taste tests using local vegetables. “It’s all about building relationships. I go into the kitchen now and I get hugs. It’s really exciting.” FARMS has developed relationships with food service workers, teachers, school board members, farms, farmers’ markets, Maine Agriculture in the Classroom, MOFGA, Cooperative Extension and more. Some classes take field trips to the farmers’ market.

Kleinkopf hears regularly that “kids won’t eat this food.”

“It’s not true,” she says. “If you expose kids to this, they will eat it.”

FARMS has applied for a grant for a farm-to-school coordinator; and Kleinkopf is excited that LD 1140 passed – tasking Maine’s farm-to-school groups to provide information about their programs. “I really believe if you can get farm-to-school coordinators … who can talk to the farmers, talk to the food service directors, and say ‘Let’s put our food dollars in with our farmers,’ that there’s a lot of hope for the future,” Kleinkopf concluded.

Quality Food for All

Heather Albert-Knopp helped launch and coordinate farm-to-school efforts in eastern Maine through the Healthy Acadia Coalition. At the Fair she discussed the importance of getting fresh, local, organic foods to all Maine people, regardless of income or education.

Albert-Knopp said that one of MOFGA’s long-term goals, and one that it’s going to emphasize more in its new five-year plan, is to help make locally grown, organic foods more accessible to all people in Maine, regardless of income – through schools, food assistance programs and other ways.

In her work, she has seen that when kids learn in hands-on ways where their food comes from, when they taste local foods, they get excited. They can taste the difference between carrots that come off the farm and those that came off a food service truck.

“I worked on a farm stand,” said Albert-Knopp, “and heard parents say, ‘My kids told me I have to come here and get the food here, because they get it at school and they love it.’”

The federal Women, Infants and Children (WIC) nutrition program for pregnant women, breastfeeding women, postpartum mothers and for children under 5 years old bases its eligibility on financial and medical or nutritional needs. The program serves thousands of Maine families – by, for example, providing vouchers for use at farmers’ markets for up to $10 or $20 per year for local and organic food. The bulk of the money in the WIC program, however, goes to families for milk, eggs, juice, cereal, beans, peanut butter, carrots and tuna – products deemed nutritionally helpful to families – but in most states, those products cannot be organic.

Maine’s WIC program, for instance, has an approved foods list (www.maine.gov/dhhs/wic/nutrition_approvedfoods.htm) that forbids organic and raw milk, milk in glass bottles, organic cheese, etc. These rules are set by the state, and MOFGA has found Maine’s WIC office to be very receptive to talking about this problem. The major reason for the restrictions is cost.

This prohibition on organic foods raises questions, said Albert-Knopp. Should parents, regardless of their income, have the right to choose foods that don’t have pesticides on them for their children? What message does this say about organic foods to parents and low-income families? Does it make people think organic is not as nutritious as other foods on the list?

The federal WIC program is authorized under the Child Nutrition Program, which expired on Sept. 30 and should be in the new Child Nutrition Act, which may not come up for a vote until next spring. This program also funds school lunch, breakfast and snack programs. This is an opportunity to change the program at the federal level, said Albert-Knopp.

Q&A

During the question and answer period, Sharon Tisher of MOFGA’s Public Policy Committee recommended the Newsweek article “Born to be Big” (Sept. 11, 2009; www.newsweek.com/id/215179), which links development of more fat cells in rats with early exposure to estrogen-mimicking chemicals found in food containers, plastic water bottles, pesticides and many common cosmetics and baby products.

Asked about obesity rates in the rest of the world, Goltz said, “All over the world, obesity rates are increasing – even in India” – but the United States is close to being the most obese nation.

Regarding the relationship of obesity to liver and kidney disease and to thyroid hormone levels, Goltz said that “thyroid problems are a rare cause of obesity.” There is a link between liver disease and obesity, he said, and an indirect link with kidney disease: “When people develop diabetes, it dramatically increases the risk of kidney disease, and we’re seeing skyrocketing rates of people needing dialysis. If you take nothing else, that’s going to bankrupt our society 30, 40 years down the road, because we’re going to wind up with 10 percent of the population on dialysis.”

This is a big problem for people who get diabetes when they are teenagers and, once they need dialysis, will be on it for decades.

Asked what causes diabetes, Goltz said that people with Type 1 tend to get it as children; it is believed to be due to a combination of genetic influences and viral infection. “That’s a small minority of people with diabetes.”

Much more common is Type 2, which used to be called adult onset diabetes. “We can’t use that term any more because so many kids are getting it.” Its primary cause is excess weight and inactivity; there is a genetic component to it; and, increasingly, chemicals have been related to it. The strongest evidence Goltz knows of is the relationship with the chemical bisphenol A (BPA).

Our aging population probably accounts for only 1 to 2 percent of the increase in diabetes, Goltz said in response to another question. Albert-Knopp noted that the Newsweek article said that overweight rates are increasing even in children under a year old. “That’s where we’re looking at some of these toxins in particular,” she said. “Their cells may have actually been programmed before they were born, because of exposure to chemicals, to process fat and calories in a different way so that they’re converting more of it into fat.”

Regarding salt, Goltz said he hasn’t seen studies directly linking salt intake with diabetes, but that high salt intake can increase blood pressure, which can lead to complications with obesity. “The food industry is adding all kinds of things that increase people’s cravings for food that isn’t very good for you,” he said.

Russell Libby noted our role as advocates for those who are not empowered to demand healthful food. “MOFGA is pushing this nationwide.”

One audience member suggested reaching out to neighbors or their kids, who may not know how to cook healthful foods and who may feel too intimidated to go into a co-op. Invite them over to cook bread with you, she suggested.

Albert-Knopp agreed and added, “There is also a policy barrier. In order for stores to accept WIC coupons, they must carry those WIC products. That also keeps those people from going into natural foods stores.”

– Jean English