|

| Writer, professor and homesteader Linda Tatelbaum amid the beauty and bounty of her garden, harvesting tomatoes growing in the south-facing, luxuriant hillside garden she and her husband, Kal Winer, have created in Burkettville, Maine. Every year she cans 300 quarts of vegetables and fruits for good winter eating. |

by Jean Ann Pollard

© 2005. For information about reproducing this article, please contact the author.

Are you living simply, gardening organically, cooking from scratch, recycling, having two kids instead of eight, etc.? Are you living the Good Life?

Or are you depressed by today’s politics, fanatics, pollution, global warming, overpopulation, and your own failures?

Take a second look. Right before your eyes are a woman and her husband who had a dream and are still in Maine, showing that dreams don’t necessarily die.

In 1973, a young Ph.D., Linda Tatelbaum, was teaching at a New Hampshire college when Watergate exploded, the Arab oil crisis hit, the college went bankrupt, and she couldn’t pay her oil bill. With her good friend, dean of students Kal Winer, she decided to “drop out, do physical labor, earn my keep on this planet,” writes Tatelbaum in her book, Carrying Water as a Way of Life: A Homesteader’s History.

Bartering farm work for cordwood, cow’s milk, maple syrup and old canning jars, she and Winer lived in his self-built, one-room cabin in the woods, ate from wooden bowls, drank from stoneware mugs, used chopsticks, and decided they’d never need money again, or alarm clocks, radios, or newspapers – except to start the cookstove. Staples would be beans and rice, vegetables, yogurt and homemade, whole wheat bread.

In 1975, they married. While she chopped wood and carried water, he ran a lathe from 9 to 5 at a factory. In 1976, inspired by Mother Earth News into believing “that somewhere in Appalachia there’d be a farmhouse and land where we can be happy homesteaders,” they joined the back-to-the-landers. They rented a small house in Canterbury, N.H., gardened, raised their own food, saved all their money, and started looking for land. After trips as distant as West Virginia and Kentucky, in 1977 they found a place where they felt at home – in backwoods Burkettville, near Appleton, Maine, where they bought 75 acres on a dirt road. Using only hand tools, including a two-person crosscut saw, “which nearly destroyed but ultimately improved our marriage,” says Tatelbaum, they cleared land, built their solar house, planted another garden.

In 1981, two years after their son arrived, Tatelbaum returned to teaching part-time. This meant getting up in the dark, fumbling with kerosene lamps, hauling water from a well. Colby College was an hour away. Winter closed in. Her dirt road was the last in town to be plowed. She left home extra early in snow, then mud, to make her 8 a.m. class. At night, reading students’ papers by Aladdin lamp, she felt “like a creature from another planet.”

Still, she and Winer, now a family therapist, persevered. By 1987 they had survived 10 years of homesteading – with a few additions: a sink drain, a cookstove capable of burning wood or propane, hot water, photovoltaics for lights, and a water pump. In 1990 they even bought a leather couch, “living with animal skins after all, in a comfortable cave that’s off the grid.”

By 1995 the improved array of solar panels even brought color TV, computers; and an acute awareness that living ‘the simple life’ is complex, that it involves hard work and, sometimes, compromise. Somehow, says Tatelbaum, it seemed enough “to eat from the garden year ’round,” enough to be “minimally responsible for the world’s pollution.” If she was home hauling water and eking out a living from the soil, was the world truly being served? “Even wood smoke from my two stoves is an air pollutant, and my solar electric panels are made from silicone, copper, plastic, rubber. I’ll never be pure unless I go live in a cave and wear animal skins. But then I’d have to kill animals, wouldn’t I?”

|

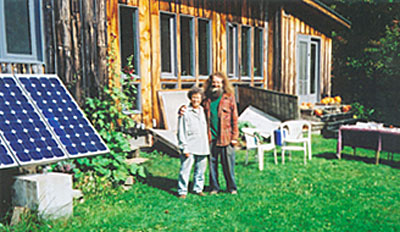

| Linda Tatelbaum and Kal Winer, dressed for gardening and for greeting visitors, in front of their self-built solar home in Burkettville, Maine, during the 2004 National Solar Home Tour. Inside the house, the aroma of Tatelbaum’s Jerk Sauce bubbling on the stove permeated everything. |

Keeping up with Helen and Scott Nearing – the quintessential back-to-the-landers – might be “just another form of rat-race … the whole idea the Nearings put forward – that the less you need, the less money you have to make, and the [freer] you are to follow your heart – made sense to us,” says Tatlebaum. The Nearings “were influential. Yet even before Jean Hay Bright’s book [Meanwhile, Next Door to the Good Life] came out, I thought they hadn’t told the whole story about how the ‘simple life’ can be difficult, how you have to adapt, how you have to be easy on yourself. Because if you try to keep doing what you set out to do at 25, you’ll never make it. You change.”

Did she and Kal?

“We used to fight about balance, about roles. Fortunately, though, we weren’t fighting about values. That’s why we’re still here, still together, and still on the land … That’s key. You both have to want to be doing it. Either that, or you have to resolve the work issue. You always hear people complaining, ‘My husband likes to plant and then I have to do the rest.’ In our case we evolved: He does seedlings and I do direct seeding. I do greens, he does garlic. And we help each other. You realize, when you’re past the really, really young stage, that you can’t be expert at everything. You have to share, and you have to explain what you’re doing. When we began, we each tried hard to do everything.”

Today they buy grains, eggs, dairy and soy products from a co-op, and Tatelbaum no longer bakes bread or makes yogurt, but she still gardens and cans 300 quarts of produce each summer. Eating from the same wooden bowl, she also enjoys “wine in a stemmed glass or setting the table with my grandmother’s china once in a while.”

Feeling a mission to tell the truth about back-to-the-landing, Tatelbaum produced two elegantly written books: Carrying Water as a Way of Life: A Homesteader’s History, self-published in 1997, and Writer on the Rocks: Moving the Impossible, in 2000.

Canning the Sun

Tatelbaum and Winer grow “just about everything” in their south-facing, hillside, organic vegetable garden in Burkettville, Maine. Asked about her cooking and canning habits, she responded, “I don’t really measure exact quantities. I cook by feel, look, smell and taste.” And she invents some unorthodox items.

Here’s her ‘recipe’ for Jerk Sauce, which is good as a condiment, she says, or as a sauce for chili, tofu, chicken, etc.

Jerk Sauce

Chop into medium-sized chunks:

5 medium-sized onions

1 whole head of garlic

1 or 2 hot peppers (depending on taste)

20 to 30 plum tomatoes

10 tomatillos

In a big porcelainized or stainless steel pot, sauté the onion, garlic, hot peppers and tomatillos until limp.

Add: the chopped tomatoes

2-inch piece of freshly grated ginger root

1 teaspoon allspice

1/4 cup blackstrap molasses

1/4 cup lime juice

Taste your concoction. Boil it down (about 4 hours) to a desired thickness. Makes about 6 pints.

Jerk Sauce can be canned at 10 pounds pressure using a pressure canner (due to the inclusion of nonacidic peppers) for 45 minutes (quarts) or 35 minutes (pints).

Check directions for using a pressure canner before you begin, and if you’re new to canning, study the Ball Company’s Blue Book: Guide to Home Canning, Freezing, and Dehydration, available from Alltrista Corporation, Consumer Products Company, Dept. PK40, P.O. Box 2005, Muncie, IN 47307-0005. Edition #32, 1991.

The 1967 edition of Irma Rombauer and Marion Rombauer Becker’s Joy of Cooking also contains good canning information on pages 746-752, as does the 1951 edition of the Woman’s Home Companion Cook Book.

A fine modern book of canning directions is Putting Food By by Ruth Hertzberg, Beatrice Vaughan and Janet Greene, The Stephen Greene Press, Brattleboro, Vermont, 1980 (2nd edition).

Tatelbaum suggests that you could can Jerk Sauce with shell beans and call it (laughingly) “Caribeans.”

Caribeans

In a deep pot, cook:

shell beans such as soy butterbeans, pole beans, or whatever you have that’s not completely dry.

Bring them just to a boil, then remove and drain them.

Fill hot canning jars 3/4 full with your still hot, drained shell beans. Add:

Jerk Sauce, leaving 1″ headroom

Push a wooden or plastic chopstick into the jar so that sauce surrounds the beans. Add a little boiling water if the sauce is really thick. Process for 65 minutes in a pressure canner (since beans are nonacidic).

Tatelbaum concocts a liver tonic, pick-me-up, and immune booster from dandelions. When mixed with soy milk she calls it “Dandy Soy”; with spices, it’s “Dandy Chai.” When school begins and kids (from elementary to college-age) bring viruses and bacteria to teachers, it’s a good time to imbibe.

Dandy Chai

In a porcelainized or stainless steel pot, place:

2 quarts water

3 heaping tablespoons roasted dandelion root

1 tablespoon black cohosh root

1/4 cup dried birch polypore mushrooms

1 large chunk of peeled gingerroot

1 dried hot pepper

optional: cinnamon bark, coriander seeds, whole cloves

Boil together for one hour. Strain, add more water to the finished brew if it’s too strong. Drink hot or cold, black or with milk.

Canned Fruit Juice

When I visited Tatelbaum’s cellar stocked with canned goods, I couldn’t believe that quart jars fruit juice in which bits of fruit floated had been ‘canned’ without processing by either pressure canner or boiling-water bath. For 30 years, however, Tatelbaum has used Helen Nearing’s method, described in Living the Good Life, and, although a jar hasn’t sealed properly a few times (and has been thrown out), she’s never suffered any bad effects. Botulinus, she says, isn’t a threat when canning with fruits, because they’re acidic.

But note: Putting Food By (2nd edition by Ruth Hertzberg, Beatrice Vaughan and Janet Greene) says that while a hot-water bath, which is pasteurization, as opposed to a boiling-water bath, which maintains a real boil at 212 degrees F., is the best process for canning sweet, acid fruit juices, certain fruits are safer when preserved with the boiling-water bath method. The book advises: “Wash jars, screwbands and lids in hot soapy water, rinse well in scalding water …. let them stand filled/covered with the hot water until used, to protect them from dust and airborne spoilers.”

So, wash and scald your quart jars

Stand each jar on a towel to prevent breakage, and while still hot pour in:

2 inches boiling water

1/4 cup honey

Stir to dissolve, and add:

1 1/2 cups clean, whole plums, grapes, blueberries, raspberries, strawberries or rosehips, etc.

To each jar, add until brimming:

boiling water

Cap with a hot metal lid. Screw down its ring. Set aside. Allow the jars to steep for at least six weeks before using.

According to Helen Nearing and Linda Tatelbaum, you don’t need to process these jars in a pressure canner or boiling-water bath, because the heat of the jar and ingredients seals the cap onto the jar easily. The juice keeps forever, says Tatelbaum, and only gets better. And you can eat the fruit.

The Great Tatelbaum/Winer Garden

Tatelbaum and Winer grow “for the two of us, plus extra to give away and in case of crop failure in one area … we’re really growing enough for four to six people.”

Basics for summer:

lettuce, spinach, peas, corn, summer squash, green beans, pole beans, cabbage, broccoli, peppers, tomatoes, cucumbers, celery

Basics for fall:

broccoli, cauliflower, kale, brussels sprouts, spinach

Basics for winter storage:

potatoes, winter squash, dry beans, cabbage, carrots, rutabagas, beets, celeriac, 800 onions of all kinds!

Perennials:

raspberries, highbush blueberries, rhubarb, horseradish, asparagus, apples and pears (without much luck)

Tatelbaum’s favorite varieties are:

* ‘Hogheart’ tomatoes

* ‘Pineapple’ tomatillos

* ‘Ailsa Craig’ and ‘Latin Lover’ onions

* ‘Burpee Hybrid’ canteloupe

* ‘All-Star Mesclun’ lettuce mix

* ‘Tiger Eye’ and ‘Trout’ dry beans

* ‘Marketmore’ cucumbers

Tips for Composting and Gardening

Tatelbaum and Winer’s solar house contains a composting toilet. Composted material is removed from the toilet tank twice a year and composted again outside with leaves. This is used on crops with edible parts that don’t contact the ground, such as fruit trees, blueberries and raspberries. It is not used with such crops as carrots and beets.

Finished compost made from food scraps, leaves and organic garden refuse is spread on garden beds in spring, while the still ‘cooking’ heap is surrounded by concrete reinforcing wire to make a cage; tomatoes are then planted around the outside and tied to the wire.

Oats are sown in strips as a cover crop in early fall, then get tilled into the garden come spring.

Cherry tomatoes are planted in Walls-of-Water for early eating.

Greens of all kinds are planted in tunnels made from lengths of black hose (for the hoops) covered with Reemay.

About the author: Jean Ann and her husband, Peter Garrett, operate a CSA from their Simply Grande Garden in Winslow, Maine. Jean Ann wrote The New Maine Cooking and, with Peter, wrote The Simply Grande Gardening Cookbook.

Dr. Linda Tatelbaum teaches Maine Literature, Writing, Critical Theory, Environmental Philosophy and Literature at Colby College in Waterville. Her son works for MoveOn.org. For more about Tatelbaum’s books, see www.colby.edu/~ltatelb.