|

| John Fuchs plants Tristar strawberries in a raised bed in northern Vermont. Photo by Deirdre Fuchs, copyright 2001. |

By John Fuchs

New England growers rarely have an advantage over southern and western growers, but strawberries offer a delicious example of a crop that is better suited to the cool, moist climate and acidic soils of New England than to the heat of the south or the dry, alkaline conditions prevailing in many Western states. New Englanders should exploit their advantage.

Site Selection

While climate and soil favor strawberry production in much of New England, site selection and proper soil preparation are essential if berries are to thrive here. Often New England growers plant crops on a south-facing slope, but in the case of strawberries, this will encourage earlier, frost-susceptible blossoming. Instead, select a sunny northern or western site that slopes slightly and drains well. Because drainage is so important – strawberry roots will not tolerate standing water for any length of time – raised beds are a good idea.

Strawberries should be planted on land that has been cultivated for at least one year or, preferable, two or three years. Sod and wireworms will wreak havoc on the roots of strawberries that are planted in newly turned grassland. Better to wait than to plant on sod. Also avoid planting where tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants or raspberries have been grown within three years, as strawberries may pick up soil-borne diseases remaining from these crops.

Strawberries do best in a slightly acidic (pH 6.0 to 6.7) soil. They like a rich loam with lots of humus – something organic growers should be able to supply in abundance. In the fall prior to planting, I work in a large amount of compost that contains some oak leaves and pine needles, two acidic components. I avoid compost that contains wood ashes, as this raises the pH considerably. I did not apply manure to my bed, but it can be utilized if it is applied in the fall. Do not apply fresh manure at the time of planting.

Which Type of Strawberry to Plant?

To decide which type of strawberry to plant, think about how the berries are to be used. A backyard gardener should determine whether he or she wants the fruit primarily for fresh eating or for freezing and/or jam making. A commercial grower will have to decide whether to have a Pick-Your-Own (PYO) operation, a roadside or farmers’ market outlet, or a more distant market requiring shipping, then search for varieties that meet those needs. Often a grower will plant several varieties to meet multiple needs.

Two types of strawberries are available: June bearers and everbearers (also know as day neutrals). Most varieties are June bearers; they produce one crop per year, in June and early July, over a period of about three weeks. Almost all commercial growers, particularly PYO growers, use June bearers, because their crop season is concentrated. Abundance draws customers to the fields and stands. A short season also makes cleanup easier and then enables growers to tend to midseason crops. The small grower looking for a niche may decide to plant one of the new June bearing varieties that actually bear predominantly in July. Markets usually offer less competition for these late-midseason varieties.

Everbearers appeal more to home gardeners, because they spread their bounty over four or five months. Some home gardeners, however, plant early-, mid- and late-season June bearers to stretch the season, usually eating the berries fresh and not making jam. Canning is not much fun in July.

Everbearers produce a nice late spring and fall crop. They also produce lighter yields throughout the summer, doing better when temperatures stay below 85 degrees. I selected ‘Tristar,’ an everbearer from Johnny’s, which provides us with fresh fruit for four months and a nice fall crop for freezing and making jam.

|

| Carefully spacing and managing runners produces a healthy bed of strawberry plants. Photo by Deirdre Fuchs, copyright 2001. |

Selecting a Planting System

The two most popular systems in the North are the spaced-matted system and the hill system. In the spaced-matted system, plants are set about 2 feet apart in the row and the rows are spaced 4 to 5 feet apart. When the plants send out runners, the grower lets them root every 6 to 8 inches, forming a mat around the mother plant. No more than a half dozen runners should be rooted; additional runners should be removed. The following spring the runners will produce their best fruit. In the third year following the harvest, most growers plow under both mother and daughter plants and plant a new bed with new plants in another location. This is the preferred strategy for commercial PYO growers who need heavy production and who have land available to start new beds. However, good production can be maintained for another year or two in the same location by removing the mother plants and lavishing attention on the daughter plants.

In the hill system, beds are raised about 6 inches above garden level. Plants are spaced every 12 to 18 inches in the row, and rows are spaced 18 inches to 2 feet apart. This is feasible because the runners are removed. The hill system results in large berries, but, because no runners are allowed to root, the bed will produce for only two or three years.

I use the hill system with one important modification: I allow each plant to set two runners, and I root these runners within the row. I believe this system is well suited to the home gardener who has limited space and who will not have other people picking in the beds. It offers the advantage of being able to place the rows closer together, and, because some runners are permitted to propagate, the life of the bed can be extended to five years. If you use this system with everbearing varieties, be sure to remove any blossoms that form on runners during the first year. By October these runners will be well rooted. In the second year, production will come from both mother and daughter plants. No additional runners should be rooted in the second or succeeding years.

|

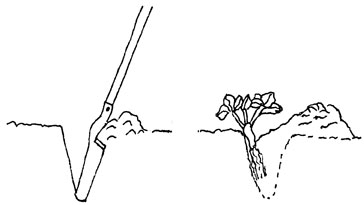

| Drawing by Toki Oshima |

Planting Strawberries

The key to success when planting strawberries is to prepare the bed the previous fall with plenty of compost. In the spring, work the soil into raised beds 6 inches high and 10 to 12 inches across. Strawberry plants should be planted in early spring. They can tolerate light frosts, and they benefit greatly from the early spring rains. Keep the plants moist until planting.

The easiest way to plant strawberries is to use a flat bladed spade to make a V-shaped planting hole about 10 inches deep. Shake the plant to untangle it and to spread its roots. Hold it against the side of the hole so that half the stem base, or crown, is above soil level. Push soil against the roots and firm it with your foot. Water well and feed each plant a pint of liquid fertilizer – fish emulsion diluted to half strength is ideal.

Give the plants at least an inch of water a week and increase it to 2 inches in midsummer. Beginning in mid-June, I apply a manure tea monthly to the plants. After pinching off the blossoms that form in May and June, I allow the blossoms to set fruit in the summer and fall. I select two runners per plant and allow them to root on the raised bed. I pick off all blossoms on the runners the first year.

Mulching strawberries with clean straw is an excellent idea. Apply the mulch 4 inches deep in June. This will conserve moisture, help keep the beds uniform in temperature and the fruit clean. I apply a winter mulch of pine needles 6 inches deep between the rows and a hay mulch 6 inches deep on top of the beds after the ground freezes in December. In the spring the pine needles can be worked into the soil. The hay mulch should be removed once the ground begins to thaw.

Varieties

Disease resistance and winter hardiness are the most important considerations for New England growers. Resistance to red stele disease and to verticillium wilt should be a high priority when selecting a variety.

For Type 1 – June bearers – the following varieties all show resistance to red stele and are winter hardy:

‘Earliglow’ – an early variety that tastes good. Medium sized and vigorous. Some resistance to verticillium wilt. It is not overly firm, however, so is not recommended for shipping.

‘Cavendish’ – Midseason variety originating in Nova Scotia. Does well in cool weather. Produces large berries for a long time. Shows some resistance to verticillium wilt. Excellent firmness; handles well.

‘Sparkle’ – A late-season variety that many growers say is the best for jam making and freezing. Medium-sized fruit. Winter hardy but not resistant to verticillium wilt.

For Type 2 – day neutrals – fewer varieties are available. The only day neutral that I have found growers using in my area is ‘Tristar,’ and that is the one I selected. It has good resistance to verticillium wilt and produces medium sized, tasty berries all season. ‘Tribute’ is said to be similar to ‘Tristar’ but produces a larger berry – so say the catalogs. Without grower verification, I suggest sticking with ‘Tristar.’

About the author: John Fuchs gets his strawberries to survive and even thrive in Bellows Falls, Vermont.

Helping Strawberries Survive the Winter

The winter of 2002-2003 brought prolonged periods of extreme cold, reinforcing the point that mulching berries is essential in northern New England. Mulching prevents the alternate freezing and thawing of the soil that heaves the plants and exposes the roots.

To be effective, mulch should be applied after the ground has frozen – usually in late November or early December. The mulch should be at least 6 inches deep and should thoroughly cover the bed. Hay is a good mulch and is widely used in New England. Pine needles and evergreen boughs can be used, also. Avoid leaves, as they clump together, become matted and lose some of their insulating ability. Snow is a fine insulator but cannot be depended upon to arrive early and stay throughout the season.

The mulch can be pulled back in April. (Strawberries can handle night temperatures in the 20s.) The beds should be rebuilt by adding well composted soil and/or drawing soil up from between the rows to the sides of the beds.

On April 17, I pulled back the hay mulch. No plants had been heaved or roots exposed. (If they had, I would have discarded them.) The following week I shored up the beds. The first week in May, blossoms appeared.