|

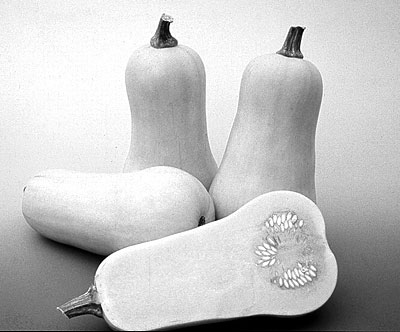

| Waltham Butternut. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

By Jean English

On a cold and snowy day in January, Rob Johnston Jr., Chairman of Johnny’s Selected Seeds in Albion, Maine, urged growers to go home after Maine’s Agricultural Trades Show and do their “winter kitchen table work. Do it tonight in front of the wood stove. Spring comes quickly … and seed companies tend to run out of things further in the spring.”

Planning and Ordering

Johnston spoke about winter squashes at a MOFGA-sponsored session at the Trades Show. He advised first scoping out markets to determine what kinds and varieties of squashes to grow; planning your acreage; and planning your greenhouse space – particularly if you’re an organic grower using untreated seeds, because transplants will be most successful in that case. “The planting window for winter squash in Maine is very small,” he noted. “If you plant before, say, June 5th or the 20th of May, depending on where you live, you’re too early for the frost date, or the nights are too cold, and seeds won’t germinate or plants will suffer” if grown directly outside. “After June 20th or 25th, you risk not maturing the crop.” With transplants, however, you can hold the plants in a greenhouse while waiting for good planting weather, and still get a crop to mature.

Next, order seeds, flats, planting mix and mulches; row covers; irrigation supplies; transplanter parts; and fertilizers early. Johnston recommends the brand Solar Mulch (formerly called IRT, or infrared transmissible, mulch), which enables a lot of near infrared light to pass through and heat the soil, but does not enable weeds to grow, because it excludes most visible light. This is not a red mulch, but is greenish in color and contains the necessary pigments worked out by Dr. Brent Loy of the University of New Hampshire.

|

| Buttercup. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

Regarding row covers, Johnston said, “If you do it right and don’t have a bad case of soil-borne insects – say cucumber beetle larvae – you probably can grow a crop without pesticides if you use fabric row covers.”

Next, “make a date with the bees.” Populations of bees have declined considerably in recent years because of mites, so Johnston recommends working with a local beekeeper if you’re growing 1/2 acre or more of squash or pumpkins. “You really need bees there to make every blossom count.”

You can till your fields and lay mulch well in advance of planting – in May, when you can work your soils. This warms the soil before seeds or plants are set. “Drip irrigation is very effective on squash,” Johnston added. “If you use it, lay drip lines before or along with laying the plastic.”

Starting Seedlings

When sowing seeds, use cells that are 2 inches in diameter, minimum, Johnston advised, and use a soilless mix that is on the dry side. “Cucurbits, especially squash and pumpkin, will really suffer if the soil or soilless mix is too moist; the seeds will rot. It barely needs to be moist with squash.” The seeds should not be sown too deeply, since roots develop primarily downward from the seed, and you want to take advantage of the entire depth of the cell.

Cover the seed with vermiculite, which inhibits the emergence of seedlings less than a heavier seeding mix. Then cover the flats to maintain a moist environment. “If you start with warm flats moistened with warm water in the greenhouse, you have a good chance of keeping them warm and not having to water again until the plants come up, if you keep the soil surface from drying. We take those plastic 10 x 20 trays and turn them upside down and put them on top of where we sow the seeds.”

|

| Tuffy. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

The sown flats should be in a warm (80- to 95-degree F.) place. “It doesn’t have to be in a greenhouse at first, before the seedlings emerge,” Johnston noted. “Watch for seedlings and remove the covers promptly” once they emerge. “You don’t want them to get leggy. As soon as plants appear, put them in direct sunlight.”

At Johnny’s, seeds are sown two per cell, then thinned by cutting the extra seedling at the base of its stem with scissors. (Growers may want to sow one seed per cell if the seed is expensive.) “Pulling it out will damage the roots of the adjacent plant, and damaging roots on a squash plant will compromise the seedling.”

Transplanting and Covering

About three weeks after seeds are sown, they’re ready to be transplanted to the field. “If you’re using a 2-inch cell, they will get rootbound after that,” said Johnston. Water the flats well with a high-phosphate fertilizer, such as a fish-based fertilizer. (Neptune’s Harvest, for example, is one that is approved for certified growers.) Then transplant.

You can direct seed squash. “You need to be a good grower to direct seed squash and sleep at night in the middle of June,” Johnston contends. “With poly mulch and row covers, you can do it – but you need to pay attention.” Jab planters work well for direct seeding, going right through poly mulch without making holes first; or you can sow seeds by hand after making slits in the mulch.

|

| Delicata. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

Install row covers as soon as you’ve seeded or transplanted squash. “Don’t wait,” Johnston warned. “As soon as they emerge, seedlings are extremely susceptible to cucumber beetle damage.” Leave plenty of slack in the row cover. “Squash grows very quickly in that environment.” Anchor the row cover against the poly mulch to control weeds close to both and to prevent a strip of weeds from growing under the row cover. You don’t need to use hoops to hold the row cover up, but Johnston emphasized again that you should leave plenty of slack.

“If you’re not using row covers, be sure the plants won’t be whipped around by the wind,” he added. “The little, leggy transplants are susceptible to wind damage.”

At Johnny’s, transplants are set out between June 10 and 14, and row covers are on for about four weeks, coming off right after the fourth of July. If plants remain under row covers any longer, the vines “are really restricted and tangled,” which stymies the plants for a while. “It’s better to remove the covers a little on the early side.” Johnston noted that you can train vines to head in particular directions so that they won’t cross one another.

|

| Sweet Dumpling. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

Keep the area between rows of plastic mulch weeded with a tractor, tiller or wheel hoe. Some people spread organic mulch in this area, either before or as soon as row covers are removed.

Harvest Mature Fruits

Harvest squash when it’s fully mature but before it’s sun-bleached, Johnston continued. Bleaching reduces marketability and can dry squashes out, reducing their quality. A light frost or two won’t hurt the fruits. Johnston urged growers to segregate puny or damaged from good fruit. “I see a lot of squash in the market that really shouldn’t be there. Feed it to your animals, compost it or plow it under; don’t market it. It won’t do anything for your reputation. Winter squash is a wonderful food; it’s like this tremendous, wonderful form of concentrated sunlight. But it’s only good when you have a nice, mature squash.”

You can cure squash in the field for five to seven days, covering it at night if frost threatens; or you can cure it in a ventilated greenhouse at 80 to 90 degrees F. for three to five days. Curing eliminates some of the moisture in the skin and toughens the skin. Fruits need not be cured if you’re going to sell them at a farmers’ market the next Saturday, but if they’re going into storage or you’re selling them to CSA members who want to store them, curing is important.

|

| Cha Cha. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

Storage

To store squashes, handle them like eggs, said Johnston; don’t bruise them. Pack them into airy containers, not in wax cartons, which don’t allow enough air flow. “A wire bound crate is perfect for squash. If you only have cardboard, cut holes in it so that more air flows through.” Keep the fruits at 50 to 55 degrees F. and at 50 to 75% relative humidity – i.e., fairly dry and with good air circulation. You may want to dehumidify your storage area for the first month or so. “If the relative humidity is over 75%, as it usually is in the fall if you keep the temperature in the 50s, or if you sense dampness in the air in your storage area,” you should dehumidify the area. “You can rent dehumidifiers. You just need them for a month or so.”

Which squash should you eat when? Johnston provided the following dates that work for him in Albion. “It’s great if you can put good quality on the table after this, but I can show you an Acorn now [in January] that looks good but won’t taste good. It’s stringy and not so high in dry matter any more.” He urged growers to pay attention to these dates if they’re supplying CSA customers:

|

| Sunshine. Photo provided by Johnny’s Selected Seeds. |

Acorn – sell by November.

Delicata – December

Buttercup/Kabocha – January

Butternut – February

Butternut, said Johnston, is a little tougher to grow in Maine, because it has a more tropical origin than other species, takes a little more heat, and is a little more risky. “But particularly with transplants, 19 years out of 20 you can bring in a nice crop, and it is the most easily stored squash.”

Favorites – Mostly from Johnny’s

Regarding his favorite varieties, Johnston leaned mostly toward Johnny’s varieties: “I’m quite fond of our squash.” Favorites are:

Acorn – ‘Tuffy’ – It’s better eating quality than other varieties on the market.

Delicata – ‘Sweet Dumpling’ is the best of all, he thinks. He also likes Cornell’s ‘Bush Delicata’ and ‘Delicata JS’ (the same as ‘Zeppelin’). “People like the small size” of Delicatas, he noted.

Green Kabocha type – “There are a lot of good ones. Sometimes these are sold as Buttercup” at chain supermarkets, “but they aren’t Buttercups. They taste really good if you throw away the puny ones and just sell the good ones,” he reiterated. Favorites are ‘Cha-Cha,’ ‘Super Delight’ and ‘Hokkori.’

Orange Kabocha “are really red, like a ‘Red Kuri,’ but are shaped like a Kabocha.” He likes ‘Sunshine,’ a 2004 All America Selections winner that is new in the Johnny’s catalog this year. “It’s an improved ‘Ambercup’ and is better quality than ‘Red Kuri’ – it tastes better, is better yielding and has prettier fruits.”

Buttercup, developed at North Dakota State University in the 1930s, originated on Bill Burgess’ farm in Fryeburg. “It’s a good thing that came out of Fryeburg,” said Johnston. “Remarkably, over the years, seed companies have managed to keep a pretty good stock of it.” ‘Burgess Buttercup’ is still the standard variety on the market. ‘Bon Bon’ is a new variety that will be in Johnny’s catalog next year. “I’ve been breeding Buttercup squash for 30 years,” said Johnston. “I’m pretty critical. I don’t think I have the ultimate Buttercup squash, but I like this new one, ‘Bon Bon.’”

Butternut – ‘Waltham Butternut’ is “another good, New England-developed variety.” ‘Butterbush’ (carried by Fedco but not Johnny’s) is an excellent eating, very small variety.

Q & A Time

Asked which pie pumpkins he preferred, Johnston answered that when they’re fully mature, ‘Baby Pam’ are fairly high in dry matter. “If they’re harvested in early September and you sell them at the farmers’ market, you may get some complaints from customers, because they don’t’ make a good pie [then]. The flesh might be really dry. All winter squashes and pumpkins start with complex starches at the beginning, and over time these are converted to simple sugars and water,” thus making better pies in October and November, after they’re not quite so dry and are sweeter. “And I’m talking about ones that have a shot at being high quality, like ‘Baby Pam,’ or, to a less but similar extent, ‘New England Pie.’

When should fruits be picked? When they’re mature, said Johnston. Eric Sideman, MOFGA’s director of technical services, commented that the more days that squash fruits are exposed to temperatures below 50 degrees, the shorter their storage life. “But don’t freak out if a light frost is coming,” Johnston responded. “A couple of light frosts won’t hurt a squash crop, and it’s a lot easier to harvest when the leaves have frosted off.” He noted that he’s never seen such a bad year for squash as last year, because of limited sunlight in August. Johnny’s squashes were noticeably lower in soluble solids last year.

Questioned about resistance to cucumber beetles, Johnston said that Butternuts and others in the Cucurbita moschata species are least susceptible.

Asked when Hubbards are best for eating, Johnston said to use them by January, as with Butternuts. And asked about smaller varieties than ‘Blue Hubbard,’ Johnston said that he’s working on this, but doesn’t have any he’s “super pleased with” yet. One grower said he was disappointed with ‘Blue Ballet’; Johnston suggested he grow ‘Blue Hubbard’ and cut it into smaller pieces to sell.

Regarding the depth of planting, Johnny’s sets transplants at the same depth as they were growing in their germinating medium. He is not aware of studies showing benefits of deeper planting.

Should side stems of squashes be removed in the field? asked one grower. Johnston said that squash plants are “pretty self restricting. As soon as they get the amount of fruit that their photosynthetic capacity can handle, they’ll stop setting fruit.” So he advised against removing side shoots.

Asked about squash bugs, Johnston said, “We have them all the time. We never do anything to control them. I don’t think they do much damage. I actually find them pretty entertaining. They have this very interesting social order, and to watch the little ones, and the big ones take care of them – it’s really fascinating.”

Grower Paul Volckhausen noted that squash bugs poke holes in his fruits, promoting rot in storage, and that they cause scars on ‘Delicatas’ that his customers don’t like. Eric Sideman suggested rotation and sanitation if growers have sufficient land, while a grower suggested removing infested leaves. Another grower noted that the eggs and young squash bugs are usually clustered in the leaf axil, and you can kill 80% of these by “crushing the hell out of them” when you first see them. Repeat this one more time, and you’ll have manageable numbers of bugs.

Finally, asked about spaghetti squash, Johnston said that he doesn’t like the hybrid variety, but prefers the original vegetable spaghetti. “Wait until it has a yellowish tone before harvesting. Don’t store it long – it’s very susceptible to black spots that rot the fruits. But if you can grow them without disease, they will store well for weeks and weeks.”