|

| The Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. Photo by Miksu on Wikipedia |

|

| Hundreds of community members exchange seeds and scionwood at MOFGA each April. English photo |

|

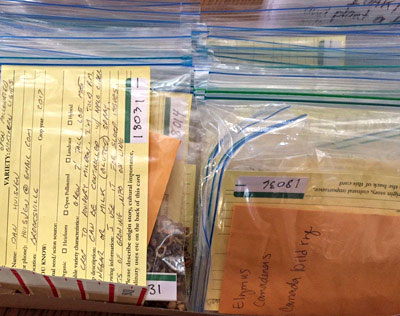

| The beginning of MOFGA’s new seed library. English photo |

By Will Bonsall

The whole topic of biodiversity and, in particular, our horticultural genetic heritage – heirloom seeds – has become a hot-button issue, and many gardeners are turning to seed saving as a way to engage with that issue. This is nothing but good; however, a number of approaches to seed saving exist, and knowing about them may help you to participate more effectively and meet your own needs, interests and capabilities. I’d like to describe the general strategies for germplasm conservation (that’s fancy talk for keeping varieties alive) and perhaps help you decide what role you might play in The Great Seed Awakening.

In Situ Preservation

The first is the oldest and simplest strategy: in situ preservation. In situ means “in place,” and it simply implies that you save your own seed for whatever crops you’re in the habit of growing and eating. This strategy is quite limited: How many crops and varieties can you possibly eat, anyway? Dozens, maybe, but not thousands. On the other hand, if having that particular item on your plate every year – especially if it’s not readily available elsewhere – depends on saving your own seed, I’m confident you’ll learn to save its seed properly, every year or so. (Fortunately seeds don’t all have to be grown afresh every year.) Saving one variety can and often does lead to more extensive seed saving, but if you go no further than this, you’ll be doing well. In fact, that’s how I first got into seed saving: merely trying to cut down my seed bill. Who knew about heirlooms and genetic extinction?

Incidentally, if everyone saves seed, won’t that be bad for commercial seed companies? No. In fact, it’s a paradox that as gardeners discover the delights of greater diversity in their gardens and on their plates, they develop a consuming lust to try even more, and by saving seed money on their current favorites, they can afford to try new stuff. That’s an incentive to the more progressive seed companies that are always trialing and adding new varieties to their catalogs.

Guilds

A downside? Saving seed of several varieties can be hard to do all by yourself. A next logical step is to save seeds collectively with like-minded friends, spreading out the work and giving everyone more variety, with larger plant populations for a deeper gene pool, not to mention sharing skills and fun. Granted, this “guild” or community strategy preserves only those varieties that all of you like to grow for your own use, but there’s nothing shabby about that.

Seed Libraries

This segues naturally into “seed libraries.” Some of these are associated with actual libraries, but there’s one critical difference: When you borrow a book, read it and return it the following week, it’s still the same book. Assuming you’ve handled it carefully, it’s unchanged from the day you checked it out. Not so with seeds. Indeed they must be taken out and renewed every so often (depending on the species) or they’ll die.

Therein lies the greatest potential risk: “Borrowers” are expected to regenerate the seed (in addition to having part of the crop for their own use), but do they know what they’re doing? Even with self-pollinating annuals (beans and tomatoes are by far the most popular crops for seed savers), there is room for error. Does the grower know how to recognize mature seed and how to ensure quality? How to avoid bean beetles and how to ferment tomato seed to avoid disease? Did the grower sufficiently isolate or hand-pollinate crops that cross-pollinate, such as corn, cukes and squash? Biennials need to be overwintered to break dormancy for the second year; is the grower set up to do that? With the “guild” strategy, you can at least know the competence of others in your group, but in seed libraries, you may have no idea who the last grower was, or the one before that person, so the viability and purity of that seed may be a crap shoot. I’m not saying it necessarily is, but a library requires ample instruction and monitoring to work.

On the other hand, seed libraries can make a relatively large assortment of varieties available and affordable. (They assume garden-scale seed samples; market gardeners needing ounces of seed will find them unworkable.) And like guilds, seed libraries encourage gardeners to get acquainted; the community/social facet of book libraries is none the less for seeds.

By the way, varieties available in seed libraries are not necessarily rare or special. Indeed, hopefully not, since seed libraries are not always reliable or sustainable over time. They are valuable for what they are, but as a vehicle for genetic preservation, they are of limited use.

Seed Exchanges

A step beyond guilds and libraries are seed exchanges. These differ in that the organization is typically only a network, with the actual transfer of seeds being directly between grower and user. The largest and best known is the Seed Savers Exchange (SSE), centered in Decorah, Iowa. SSE compiles a catalog called the Winter Yearbook of all the varieties offered by the many listing members. The word “members” may be misleading, as none of the listers has any say in the operations and policies of SSE, much less those who merely pay to get the catalog but are also called “members” nevertheless. The only way a grower “participates” in the organization is by offering or requesting seeds from other “members,” but given the access to many thousands of varieties – many rare or unusual – that is vast. Again, an important feature of SSE and other exchanges is the social connections. I’ve made many dear friends and exchanged an ocean of knowledge with other SSE members.

The Grassroots Seed Network was founded as a democratic alternative to SSE, although like many democracies it is struggling to get momentum. Several smaller regional seed exchanges exist, as well, such as Upper Valley Seed Savers in Vermont; and other countries have similar exchanges, such as Seeds of Diversity Canada, Noah’s Ark (Austria) and SESAM (Scandinavia). Such organizations are typically powerful in their range of offerings and reach of participants, but they cannot guarantee the quality or purity of seed. That being said, I’ve rarely been disappointed with seed from such exchanges.

These exchanges do not necessarily have a long-term backup. (SSE does, although concerns about it exist). An exchange like SSE offers a great deal of resilience in that many seed recipients will offer those varieties again, duplicating many listings and providing safety in redundancy – and many varieties continue to be offered decades after the original lister is dead.

The exchange model differs from the other strategies in that it is not intended to be merely a source of seeds to grow, like a seed company, but a vehicle for genetic conservation, especially of rare or unusual varieties. It is intended, or at least hoped, that you will “adopt” those varieties you request, for your own long-term use and to further share.

Seed Banks

Over the years, many people who were superficially enthusiastic about seed preservation have started “seed banks.” This usually involves buying one or more chest freezers and filling them with seeds, often purchased from seed companies, although during the Y2K scare, I was deluged by huge requests for “heirloom seeds” from people who had never planted a garden in their life. Many of those folks were the same types who stocked up on 5-gallon tins of peanut butter, bottled water and, of course, ammunition, to store in their cellar or cabin in the Rockies. I wonder what happened to all that seed when the year 2000 rolled by with no grid blackouts or massive looting.

Seed banks are only about storage; no regeneration is involved, hence you needn’t know what you’re doing. Even the bank analogy is flawed: After all, real banks send their money out to make more money. That is not to say that seed banks haven’t a place as a temporary backup in the event of a short-term crisis. As in the Noah’s Ark myth, no one expects to live there, just to stay alive until the waters recede.

The most recent and well-publicized example of a seed bank, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, has drawn a lot of controversy, which I believe is largely ill-founded. It does no harm and could be extremely useful under some circumstances. However, most people agree that it cannot replace other strategies for sustainable preservation. Nor is it reliably accessible; like a time-capsule, seeds are placed in there only once and are meant to be taken out only once. Such collections are highly centralized and thus vulnerable to natural and manmade disasters. An important rice collection in Thailand was destroyed by catastrophic flooding, and a globally important wheat collection was subjected to U.S. bombing during the Iraq war. Obviously backup is critical although often inadequate.

Another extensive seed bank is the USDA National Laboratory for Genetic Resource Preservation (formerly the National Seed Storage Laboratory) at Fort Collins, Colorado. It is the epitome of long-term: Seeds stored in liquid-nitrogen-cooled chambers are in a suspended animation induced by super-cold temperatures. They’re good for many decades, perhaps much longer. But like Svalbard they are not readily accessible, especially by the general public. They rather serve as a backup to the rest of the National Germplasm System, located in various facilities around the country. These are a whole other category: the “active repositories.”

Active Repositories

Active repositories are somewhat like seed banks in the huge number of accessions maintained there, but they differ in being “working collections.” Their accessions are regenerated periodically to assure long-term viability and to create large enough stocks for distribution. They are available to end users (breeders, researchers, etc.) upon request, although not necessarily to the general public. Such facilities are eager to receive feedback on requested samples, especially notes about trials; that makes the accessions more valuable to other requestors. They generally do not require or even want the return of any seed increase; due to uncertain competency, they prefer to do all their own regeneration, in contrast to seed libraries. Thus you cannot participate in those in any capacity other than requestor, if that. I’ve had pretty free access to those collections, since they view me as a collaborator. I’ve even supplied them with much material they didn’t have – and by increasing and further sharing with others, I’ve been able to encourage their wider use among the general public while reducing the burden on those facilities.

Which brings me to my Scatterseed Project. It is very much a working collection; that is, I put great emphasis on keeping varieties available to the general public, both to maximize revenues from sample fees and to encourage “in situ” conservation in the horticultural landscape of private farms and gardens. In that respect it is an active repository. It is not a seed bank, as I do not yet have freezers for longer-term storage (but I hope to). It is not a seed library, as I insist on doing all the propagation on-site, although occasionally I cooperate with growers of proven competence. Partly for lack of those features, my collections are currently in shambles. Three years of slashed funding have left most of the collections at great risk from my inability to regenerate them soon enough. Yet most potential cooperators are interested or experienced in self-pollinating annual beans and tomatoes, which are not my greatest need, whereas the real need is for help with cross-pollinators and biennials, such as parsnips, rutabaga, radishes, etc.

A great help will be to install freezer backup in the new office; freezing triples the viable life of seed samples properly stored in air-tight, moisture-proof packets. This requires more funding to finish construction of the new office and install freezers, which is not allowed in this year’s budget. Unlike government and institutional repositories, Scatterseed does not have a reliable revenue stream but depends largely on private donors (including a generous annual subsidy from Fedco) and occasional volunteer labor.

What’s Best for You?

What role might you play in this exciting endeavor of genetic conservation? I generally do not encourage seed banking, which is at best a short-term stopgap; however it can be a critical backup to the other strategies. For example, if you do no more than save your own seed, you will have done very well. You’ll be far more efficient if you have a dedicated seed freezer so that you don’t have to save seed of everything every year. In fact, refrigeration or freezing helps with any seed-saving strategy, enabling larger and less frequent grow-outs, which reduces wasted resources and minimizes the risk of genetic drift and contamination accompanying each regeneration. And unlike produce stored in a freezer, seed is not damaged significantly by a temporary power outage.

You can join a seed exchange such as SSE or GSN to gain access to greater diversity while sharing with others, or you might start a guild or smaller seed-saving community of your own. And of course you can also help support what others are already doing. To paraphrase the slogan of the Maine Forest Service: Keep Maine Green – Send Money.

About the author: Will Bonsall lives in Industry, Maine, where he directs Scatterseed Project, a seed-saving enterprise. He is the author of “Will Bonsall’s Essential Guide to Radical Self-Reliant Gardening” (Chelsea Green, 2015). You can contact him at [email protected]. See our “Daytripping” feature in this issue of The MOF&G for dates when you can visit Bonsall’s Khadighar Farm.