|

| Eli Rogosa talked about her heritage wheat project (www.growseed.org) when the Organic Seed Alliance met at MOFGA’s Common Ground Education Center in July. The event was open to the public and, as part of MOFGA’s Farm Training Project, was well attended by MOFGA apprentices and journeypeople. English photo. |

by Jean English

The Organic Seed Alliance (OSA) brought a powerful message of hope for a return to agricultural sanity when its board met in Maine in July 2008, visited farms and seed companies (Johnny’s and Fedco), and gave talks and toured plots at the Common Ground Education Center of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association in Unity.

Board member Jim Gerritsen of Wood Prairie Farm in Bridgewater, Maine, said that the OSA was founded because organic seed has great potential to create viability and stability within the organic food production system. Dan Hobbs, executive director of OSA, noted that the organization started after the Port Townsend, Washington, Abundant Life Seed Foundation – a network of over 100 growers who conserved heirloom varieties for 30 years – burned down in 2003.

The OSA no longer directly handles or sells seed but facilitates work with farmers, seed savers, university colleagues and seed companies. As Gerritsen explained, the goals are to promote a better supply of quality organic seed that is locally adapted to conditions on organic farms. “We need to be free from the consolidation that’s going on, typified by Monsanto buying up seed companies. If we’re going to be a viable, sustainable organic community, we’ve got to be independent in our seed resources. There’s tremendous potential to breed varieties that are designed to work under organic conditions. Contrast that with some of the new introductions bred under highly pampered, highly chemical conditions – they need those chemicals to prosper. We want locally adapted varieties suited for organic growing. OSA is the tool to promote that.”

Multiple Seed-Related Programs

Hobbs said that the OSA is working to improve the quality of organic seed partly through a producer cooperative (to launch in 2009) and through educational events and technical assistance.

The OSA also sued the USDA for releasing genetically engineered Roundup Ready beets last winter. Policy work is now carried out through the recently incorporated Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (OSGATA), a 501(c)5 membership organization of farmers, organizations and industry members. Gerritsen is on the board of OSGATA, which held an organizational meeting last February and will hold the first of its regular, annual meetings this winter, probably in Washington state.

Another budding branch of OSA is a producer cooperative, the Family Farmers Seed Cooperative, which will include clusters of seed producers throughout the country focusing on crops that do well in their areas. The Coop, which was awarded a $120,000 USDA Value-Added Producer Grant this September, will market to seed companies such as Fedco, Johnny’s, Seeds of Change and others.

The OSA holds an Organic Seed Growers’ Conference every other year, attracting some 300 growers from all over the country to the Northwest. It is considering holding an off-year, one-day symposium in another part of country.

The World Seed Fund, OSA’s charitable arm, collects overproduced seeds (usually open-pollinated varieties) and sends small lots to those who need it, such as community gardeners, in 60 to 70 countries.

|

| Bill Tracy (left), a noted plant breeder from the University of Wisconsin, has a Participatory Plant Breeding project going with Martin Diffley. The two are seeking a sweet corn with good early vigor, good flavor and weed resistance. Photo courtesy of Bill Tracy. |

Participatory Plant Breeding

The OSA also facilitates “participatory plant breeding” (PPB), in which farmers participate in breeding crops that are adapted to their farms, with help from university plant breeders. Bill Tracy of the University of Wisconsin described two models of PPB that he’s worked on. One involved helping Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seed in Oregon breed an open-pollinated sweet corn that germinates well in the cold spring soil of coastal Oregon and produces a vigorous, fast-maturing crop with two ears per stalk of tasty corn with good texture … in a short growing season and in an organic system. Morton also wanted a red pigment in the leaves and stems, which, anecdotally, seems to be related to resistance to harmful soil fungi.

Morton conducted mass selection for the above traits from 2001 to 2006. One selection procedure involved wrapping seeds in wet paper towels, placing them outdoors, and then transplanting the seeds with the longest coleoptiles (the emerging shoot), using the hypothesis that long coleoptiles indicated more rapid germination.

In 2007, plant breeder Jim Myers of Oregon State University found that one of Morton’s earliest maturing, as yet unnamed varieties had good flavor and texture. A trial sown in mid-April (very early for coastal Oregon) and evaluated in June showed that an untreated check germinated at 3%; ‘Incredible’ SE (sugary-enhanced) corn germinated at 6%; and Morton’s corn germinated at 56 percent. The highest germination rate – 87% – occurred when ‘Incredible’ was grown with several chemical treatments.

Tracy is also working with Minnesota organic farmer Martin Diffley to get a sweet corn with good early vigor, good flavor and weed resistance. Diffley planted about 200, 12-foot-long “family rows.” Each family row comes from seed of one ear of corn with the desired traits, and the 200 varieties contain a lot of genetic variability. Tracy gave some seed from each ear to Diffley and kept some himself. After Diffley identified desirable families, Tracy grew those in a winter nursery in Florida and gave that seed to Diffley for further selection. “All I’m doing,” said Tracy, “is recycling seed for him, which reduces what he has to do at the busiest time of year.”

Tracy noted that selection is extremely powerful, is usually remarkable and predictable, and is precise; that just seven cycles of selection can easily change a population significantly. “We apply the selection pressure, and then the plant actually decides how to get there. This is so different from genetic engineering. In genetic engineering, we insert a gene, and that’s the way the plant is going to be. In selection, the plant actually decides the mechanism by which it’s going to make a new type, and then we enjoy the benefits. Most plant breeders have a lot of fun doing this.”

As an example, Tracy’s photos showed how, just using visual, mass selection over seven cycles, he took an ear of corn and ended up with a field corn, while selecting from the same variety in another direction produced a more extreme sugary corn.

“The key point, however – and this is a point that is lost on most geneticists – is that the genetic, biological, biochemical and physiological changes underlying that response are completely unexpected. When I show this to biochemists, they refuse to believe it. They said, ‘That’s not possible; you cannot do that with the genes that you’re starting out with. You must have had a contaminant. You must have made a mistake.’

|

| Wheat breeder Steve Jones from Washington State University is decentralizing plant breeding, for the benefit of farmers and consumers. Photo courtesy of Margaret A. Gollnick, Washington State University. |

“We can prove that we didn’t make a mistake. The biochemists say that this is impossible. Fortunately I’m not a biochemist. All this variation we see around us is the result of selection giving us unexpected types.”

Defiant Wheat Breeding in Washington

Wheat breeder Steve Jones from Washington State University (WSU) discussed “Breeding in Public – The Re-decentralization of Plant Breeding.” Today, he said, “agriculture is centralized and globalized and completely screwed up,” with farmers subjected to lawsuits over patents if they save their seed – “even though, for 10,000 years, growers had the right to plant back what they grew. In our generation, that’s going away.” Biotech, asserted Jones (who studied the subject at UC Davis), “is about ownership and nothing else” – and biotech companies “are working with your Land Grant universities.”

We got to this point, he continued, “because we declared a war on nature, and agriculturists jumped into that war on nature.” For example, Nobel Peace Prize winner and wheat breeder Norman Borlaug wrote in 1972, at the peak of the war on nature, that being “in balance with nature is a biological myth” and he referred to “The current vicious, hysterical propaganda campaign against the use of agricultural chemicals…” Jones noted that the agricultural industry substitutes the word “biotech” for “chemicals” now.

In contrast, “Where we were was a beautiful place.” Jones talked about Cyrus Pringle, a Civil War-era conscientious objector from Charlotte, Vermont, who was tortured for about three months for refusing to pick up a rifle, until Lincoln pardoned him. Pringle became the first U.S. wheat breeder, releasing his first variety, ‘Defiance,’ in 1870.

A little later, William Jasper Spillman became the first wheat breeder at WSU (Jones is the fifth), started making crosses in 1898, released his first variety in 1905, and gave seed freely to growers. “He left variation in those lines so the growers could develop far more varieties,” Jones noted.

|

| Cyrus Pringle of Charlotte, Vermont, was tortured for his Civil War-era conscientious objector status. He later became the first U.S. wheat breeder, releasing his first variety, ‘Defiance,’ in 1870. Photo from “Life of Cyrus Guernsey Pringle,” by Helen Burns Davis. [Source] |

A champion of small, diverse farms, “Spillman went to the farmers themselves. He wrote the farmers in the Pacific Northwest letters. He took the train…he rode his bicycle to go see them.”

Spillman also wrote to Henry Ford around 1915, saying, “Your tractors are too large. You need more farms that are more efficient, that keep diversity on them. We need animal integration, we need crop rotations…”

“Guess what?” said Jones. “It’s all wheat out there.”

In 1924, Spillman wrote The Law of Diminishing Returns, coining that now-common phrase and showing that spending money on inputs (fertilizers at that time) was a waste after a certain point. “Biotechnologists should read this book,” said Jones … acknowledging that they probably won’t.

Spillman’s (and his wife’s) ashes were spread on the WSU campus, within 100 feet of Jones’ office. “That’s a beautiful history,” said Jones. “That’s what’s getting screwed up.”

Jones is trying to “return some normalcy” to agriculture by breeding wheat (including perennial varieties) and working directly with growers, on their farms. His program evaluated, on organic farms and with input from farmers, 163 wheat varieties that were grown in Washington from 1842 to 1950 – “the heyday of low-input in our wheat” – and he is now crossing some of those with modern varieties.

While varieties grown in 1880 yielded poorly, and the highest yielding varieties were from 2000, Jones found that varieties from the 1920s and ‘30s yielded essentially as well as those grown now on certified-organic land in the Pacific Northwest.

Comparing varieties grown under conventional and organic systems (a plowed-down pea cover crop and chicken litter fertilizer) in Pullman showed good variation among varieties, and some varieties yielded 128 to 152 bushels per acre on animal-integrated organic farms.

Jones is often asked, “Why are you going to make us grow organically, so we’ll starve?” He responds: “The average [wheat] yield in Kansas, with as many inputs as they can dump on it, is 36 bushels per acre.” He jokes: “We’re going to starve if we keep growing [conventional] wheat in Kansas.”

|

| One of Washington State’s up and coming wheat breeding lines, WA007977. Photo courtesy of Margaret A. Gollnick, Washington State University. |

The key to growing organic wheat, he continued, is to have animals integrated on farms. Weeds can be controlled with a spring tooth harrow, and diseases can be controlled organically, but getting nitrogen to the farm is a problem. “In the Pacific Northwest, there are no more animals on wheat farms.”

Most of the 2.5 million acres of wheat in Washington are conventional. “We’re trying to reduce inputs for these growers,” said Jones.

To serve organic growers, WSU has 11 certified-organic acres on campus “We don’t believe in ‘almost organic,’ ‘kind of organic.’ We believe in certified organic. We go through the same hassles that the growers do.”

When Jones grew 35 identical lines of wheat under conventional and organic systems, he found that the fourth top line in a conventional system ranked last in the organic system. Generally, the worst lines in organic systems were the best in conventional. “That’s a problem if you have one breeding program. If you’re selecting in a conventional system for organic, you’re selecting the wrong wheats… So we have a separate breeding program for organic.”

One approach to breeding wheat is to have farmers breed their own varieties, “the way they did for 10,000 years.” Jones showed a 1908 publication from Cornell that told growers how to breed their own wheat.

Fifty years ago, Coit Suneson at UC Davis developed an evolutionary plant breeding method, which Jones and some Washington farmers now use. “First you need variation in your field,” Jones explained. “We generate that for the growers. We put it out there in the second generation, and then we allow nature and the growers to select the best varieties.”

As an example, Jones cited Jim Moore, who grows dryland wheat with about 8 inches of rainfall per year. About 10 years ago, Moore asked Jones how he could get his granddaughter Lexi interested in the farm. Jones suggested that she breed her own wheat varieties.

“Lexi came onto campus,” said Jones, “she made the cross, she developed the second generation, she put it on their own farm. Now she and her grandfather go through a few acres of wheat on a summer evening and look for plants they don’t like.” They harvest the remaining crop, save about a bushel and sell the rest.

“As they keep doing that, over time these varieties become adapted to their location. They have three varieties now – ‘Lexi 1,’ ‘Lexi 2’ and ‘Lexi 3.’” ‘Lexi 2’ beat the top hard red winter wheat grown in Washington by 8 bushels per acre this year – and Lexi herself received a full, four-year scholarship to WSU.

“Breeding takes time,” Jones continued, “but basically wheat breeds itself. It’s not like corn or squash or melons. When you harvest it, that’s it.”

Among the traits being studied at WSU are nitrogen use efficiency and the nutritional content of wheat. “We’ve been breeding wheat at WSU since 1894” but have been testing its nutritional content only for the past four years, said Jones. “We now know that we can double the iron and zinc in whole wheat grain for free – basically from use of the old varieties.”

Jones mentioned another grower who raises certified-organic Emmer wheat using a “sort of Tom Sawyer lease program” in an area where land was taken over by Microsoft and Boeing employees who retired with millions of dollars on farms just east of the Cascades and then neglected the land. The grower went from door to door asking, “How would you like to have an organic farm in your front yard?” and telling the retirees, “I’m going to do that, and I’m not going to charge you anything!”

Jones also showed a photo of “wheat anarchists” in France who are working with farmers there to develop their own, semi-illegal wheat varieties. (Growing heirloom wheat is illegal in France, due to very strict seed selling laws.) Jones and his coworkers are helping these breeders.

Regarding the trend to “buy local,” Jones said, “I don’t believe that local is better than organic. When I talk in Washington, I say, ‘Oh, so you just want to localize all the chemicals in one place.’ This is a dangerous trend in the Pacific Northwest. It’s holding down the organic wheat acreage” to about 4,000 acres in Washington. Saskatchewan, in contrast, has over half a million acres of certified organic wheat.

Maine Wheat

Another approach to growing wheat is to use it in rotations with vegetable crops – something Jones is looking at in high rainfall areas, such as the Seattle area, Maine and Vermont.

In 1880, Maine grew 40,000 acres of wheat yielding 14 bushels per acre; in 1930, the figure was 2,000 acres at 21 bushels per acre – yields that were above those of Washington at the time. In 1946, Maine grew fewer than 1,000 acres of wheat. By the mid-1880s, all of New England wheat acreage was decreasing because of rail transportation.

|

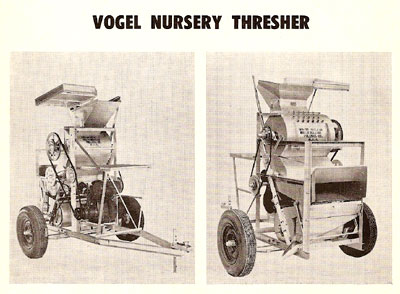

| “You can easily grow an acre of wheat and harvest it by hand and put it through a thresher,” said Steve Jones. He noted that old threshers, suited to small acreage and once made in Pullman, Washington, are widespread but hard to find for sale. Image courtesy of Margaret A. Gollnick, Washington State University. |

“There is demand for local wheat in Maine,” said Jones. “Growing wheat is easy. Harvesting it is not” without a combine and on-farm storage. At WSU, researchers harvest acres and acres of wheat with a small, serrated Japanese sickle that doesn’t have to be sharpened; they gather it into bundles if they have a lot; and thresh it in small “nursery” threshers.

“You can easily grow an acre of wheat and harvest it by hand and put it through a thresher,” said Jones. He showed a photo, taken in Afghanistan, of a thresher developed and manufactured in Pullman, Washington. “These threshers are everywhere” but are hard to purchase. Old combines are not hard to obtain – even free – but if you buy one, “buy two or three,” Jones suggested, “because it’s going to be hard to get parts.”

Jones concluded, “We believe that farmers can breed their own damn varieties. They have for 10,000 years. We started breeding wheat at WSU in 1894. We didn’t start from scratch. We started from some very highly developed varieties that were brought from Russia, Australia, Spain, Chile…

“We need to diversify our agricultural fields,” he added. “We need to diversify our science” – a challenge as most Land Grant universities continue to build biotech buildings and programs while investing little in organic and sustainable programs. Jones’ program, which currently includes four Ph.D. students, takes no corporate funding and is under no corporate influence.

For more information about the Organic Seed Alliance, including proceedings from its 2008 conference for seed growers, visit www.seedalliance.org.

|

| ‘Dorinny’ is an open-pollinated, cold-soil-tolerant sweet corn variety available from Wood Prairie Farm. Megan Gerritsen photo. |

‘Dorinny’ Sweet Corn: Early, Vigorous, Tasty Canadian Heirloom Now Produced in Maine

Working with renowned University of Wisconsin sweet corn breeder Dr. Bill Tracy, Maine’s Wood Prairie Farm trialed open-pollinated sweet corn varieties and confirmed that the heirloom ‘Dorinny’ is unmatched for short season organic corn growing.

‘Dorinny,’ a Canadian heirloom, is a cross of ‘Golden Bantam’ x ‘Pickanniny,’ bred at the Ottawa Central Experiment Farm during the golden age of traditional plant breeding, the 1920s to 1930s. It received the Market Gardener’s Award of Merit in 1936. Ironically, seed companies at that time came to favor proprietary F1 hybrids, largely because they generated greater profits by creating a market of reliant annual seed purchasers. Open-pollinated varieties, on the other hand, empower growers to select for specific characteristics and regional adaptation. ‘Dorinny’ was just one of many excellent open pollinated varieties left behind in the dash toward hybrids.

‘Dorinny’ is reliably cold-soil tolerant, a significant factor in giving organic growers excellent germination from early spring plantings for the very earliest of sweet corn crops.

At 75-days to maturity, ‘Dorinny’ is 10 days earlier than ‘Golden Bantam’ yet still possesses that variety’s famous golden-colored kernels and incredible flavor. Cobs are 6 to 7 inches long with eight rows of well-filled kernels. While best picked at peak freshness, ‘Dorinny’ has a wide picking window for tenderness compared with most open pollinated sweet corn varieties, significantly increasing its practicality and enjoyment. The vigorous, robust, 4- to 5-foot-tall plants support two ears.

Wood Prairie Farm is the first seed farm to grow and reintroduce organic ‘Dorinny’ to American gardeners. Seed packets are available for $3 from Wood Prairie Farm, 800-829-9765, www.woodprairie.com.